The Development of Crude Oil Tankers; A Historical Miscellany. By Dr Ray Solly. Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2021

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

Ray Solly’s initial career was in the Merchant Marine as a navigating officer on a variety of merchant ships, including tankers. He moved to teaching in independent schools while maintaining his connection with maritime matters by lecturing in navigation part-time. More recently, he renewed his practical seamanship skills through supernumerary attachments on North Sea tanker operations.

As such he is well qualified to write this ‘miscellany’ which will appeal to anyone interested in ships.

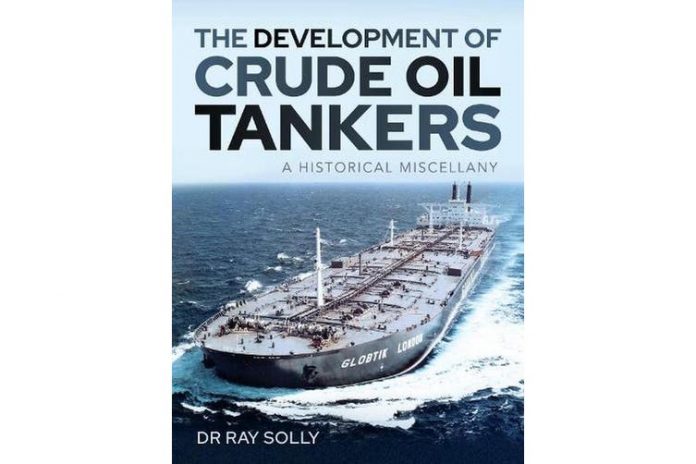

The book’s main attraction is the numerous photographs of enormous tankers. Although ubiquitous on the world’s sea-lanes, they fleetingly inhabit bleak industrial piers to discharge their cargoes only to set off again to equally bleak and remote loading points, mainly in the Middle East.

Ray Solly presents a historical treatise on the development of the crude oil tanker which began around 1863 with the first iron-hulled sailing ships bult to carry crude oil. These were followed, almost in parallel, by purpose-built steam ships (with sail assistance); The first of these was the British-built Glukauf in 1865. Solly leads us through developments in tank and hull designs to cope with cargo leakage, toxic fumes and sea-state stresses. He accompanies these descriptions with supporting photographs and internal tank drawings.

Tankers grew on size through the first half of the 20th century, the majority of which featured the ‘two island’ superstructure. The ubiquitous US-built T2 tankers predominated from the 1940s, many staying in service until the 1970s However, the post-war world demanded vastly more oil products to sustain the growth in motor vehicle use and to power new industries leading to the development of the Very Large/Ultra Large Crude Carriers. Technical innovations in cargo handling, safety regulations and environmental considerations took effect steadily from the 1980s, none more so than those stemming from the Exxon Valdez disaster of 1986. Tankers were mandated to be double-hulled by 2010 and mariners subjected to drug testing. The poor environmental record of tankers was addressed through international regulation and oil spills became a charge on the shipping company.

Solly provides a potted description of representative tankers through the ages, supported by a photograph of the vessel, and a diagram of the ships’ layouts for the more significant examples. He devotes chapters to singularly significant vessels such as Arosa, the first double-hulled V/ULCC, with photographs of its construction phases. Another is the gigantic Jahre Viking; the photographic record of which includes an image of her half-demolished on the notorious ship-breaking beach of Alang in 2009.

Beauty may well be in the eye of the beholder. In my subjective opinion the tankers of the 1930s and 40s exuded a handsome no-nonsense work ethic. Post war growth in tanker size came with a pleasing ‘streamlined’ rounding of superstructure well-set off in the ‘two island’ design. With the arrival of the VLCCs, with all superstructure aft, beauty gave way to the prosaic.

Solly’s more recent refamiliarization with tanker operations is described in the chapter Transporting North Sea Oil in which he joined the shuttle tanker Anna Knutsen at Tranmere in the Mersey River. The Knutsen’s voyage was to a North Sea installation to load oil directly via a transferrable pipeline. Held by dynamic positioning, equipment on the Knutsen lifted the pipeline to the ship’s connections allowing discharge into the tanks. The operation is illustrated by Solly’s photographs.

The second voyage was in the BP tanker British Ensign from Rotterdam to Antwerp. Solly narrates these voyages from an operator’s viewpoint, noting the many changes that had taken place since he was a professional mariner. Again, this voyage is covered in numerous images of bridge equipment and charts. A photograph of the British Ensign’s master on the bridge elicits this caption comment: ‘the crew of the vessel were all Indians, with me as the only white person aboard but, having spent many years at sea serving with associated Asian crews, this situation presented no problems’. Some might interpret this as a trifle insensitive or as one of the reasons many ‘white men’ left the merchant marine in the 1970s and 80s as the industry transitioned.

There is no mention of naval tankers – the only reference is to nine Shell tankers converted into Merchant Aircraft Carriers in 1943, one of which, Ancylus, is pictured. However, as the book deals with crude oil tankers, naval underway replenishment ships strictly fall outside this remit.

There is little to fault in The Development of Crude Oil Tankers. Written by an experienced operator, supported by superb photographs and drawings, the book can only be described as a ‘must have’ for ship enthusiasts.