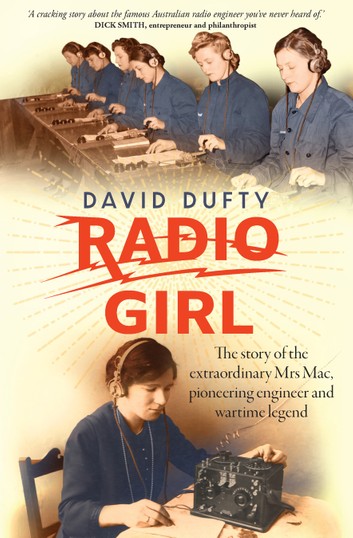

Radio Girl; The story of the extraordinary Mrs Mac, pioneering engineer and wartime legend. By David Dufty. Allen and Unwin, Sydney. 2020.

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

Violet McKenzie was a diminutive, modest but formidable individual. Throughout her life she battled institutionalised discrimination against women, particularly in the professional and technical spheres in the first half of the 20th century. She overcame misogynistic and bureaucratic obstructions to train thousands of women and men in morse and signalling skills and directly influenced the establishment of the Women’s Royal Australian Navy Service (WRANS) and the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) during World War Two.

Loved by the women, and most men, she trained for the armed forces, the ex-WRANS Association was foremost in working to retain her memory, but with the passing of time the significance of her work and legacy was in danger of being lost. This book has done much to rectify that.

She was born Florence Violet Wallace in 1890 and spent her early life in the town of Austinmeer, south of Sydney. As a child she was fascinated by electrical circuits which her father had rigged up. She qualified as a mathematics teacher in 1913 but soon realised this was not her calling and decided to study electrical engineering. Here Violet met her first obstruction as she had to be apprenticed and no one would employ her as such. Her innovative ‘work around’ was to purchase her brother’s failed electrical business and apprentice herself to herself. This satisfied the requirement to enable her to achieve a diploma in electrical engineering.

Setting up the ‘Wireless Shop’ in 1921 she sold electrical equipment but became enamoured of wireless telegraphy and the morse code. Wireless was booming in the 1920s and her shop became a mecca for waves of enthusiasts eager to be part of this new era. The book is liberally laced with excerpts from contemporary newspapers, mostly condescending and naïve, about this strange young woman in a man’s world – and doing extremely well. The Bulletin in 1924 observed: ‘Nearly every boy who owns a crystal set knows Miss Wallace’. The Sun in 1922: ‘Petite and frail to look upon, she has obviously boundless energy and an indomitable will’. The book’s title ‘Radio Girl’ was the heading of a feature article on her in the Sun newspaper in September 1923.

Modern readers will doubtless cringe at these descriptions and will be annoyed at the stubborn refusal of authorities to recognise Violet’s ideas and motivation as potentially great national assets. However, we must accept that these were the attitudes of the time and that is why this book is such good social history.

Violet was a natural businesswoman as well as being technically gifted. Her business flourished: she published ‘The Wireless Weekly’ magazine in 1922, became the ‘first woman’ to join the Wireless Institute of Australia, sponsored radio clubs, began a radio school and formed The Electrical Association for Women (EAW).

With the emerging availability of electrical home appliances, inattention to the dangers of electricity was causing fatal electrocutions, aggravated by the lack of safety regulatory oversight. Violet saw the need for women to be educated in the dangers and advantages of the appliances: ‘Think of the fatalities that would be averted if women had a general knowledge of electricity and electrical appliances’, she wrote in 1931. To this end she held seminars for appliance customers in major retail outlets.

In the late 1930s Violet saw a need to encourage women to be trained in technology to serve in a national emergency. She helped organise the Australian Women’s Flying Club in her EAW clubrooms to ‘see Australian girls able to obtain through training in all branches of aviation at a reasonable cost’. The organisation adopted a practical working uniform and held training camps. It was, of course, decried by the authorities particularly the Minister of Defence. However, it was the Women’s Emergency Signal Corps (WESC) which raised Violet and her associates to national prominence.

Violet formed the WESC to provide trained telegraphists to supplement men in a national emergency. The WESC was open to any woman with basic education and it was an instant success. Set up initially in the EAW rooms, it moved to a former wool storage building in Sydney. Her husband Cecil (she had married in 1924) installed rows of tables and morse keys and soon hundreds of women joined to learn morse; the better students becoming instructors.

With Australia’s at war there was an instant demand for trained communicators. Air force recruiting was log-jammed with applicants being told to go and learn morse to a minimum of 10 word per minute. The WESC was able to provide this training but Violet and her team’s attitudes now changed. No longer aiming to replace men operators on an ad hoc basis, they wanted to enlist.

Violet obsessively pursued this aim. She gained in-principle support from the Chief of the Air Staff, Sir Charles Burnett, but air force hide-bound opposition thwarted even the CAS. Violet ‘gave up’ on the air force and turned to the navy. Here it was a different story in the form of Commander Jack Newman, Director of Signals and Communications at Navy Office and a skilled communicator. Newman tested several of the WESC women and, following a meeting between Violet and the Naval Board, 14 newly entered WRANS telegraphists arrived at the Harman station, located on a desolate plain outside of Canberra, on 28 April 1941.

At almost the same time the RAAF relented and began accepting Violet’s graduates. As the war progressed men were sent to the Sydney school, still termed the WESC. These included allied personnel such as US Navy trainee signalmen drafted to sea before completing category training. The WESC trained over 3000 women and 12000 men for the armed forces. Violet sought no payment for her instruction; she only asked each trainee for a photograph which she posted on the school walls having funded the WESC school from her pre-war business earnings. Post war, the school continued to train civil aviation and merchant marine personnel. It closed in 1953 and Violet moved to instruct at a merchant marine school until retiring in 1955. She died in 1982.

Awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1950, Violet McKenzie was loved and revered by her thousands of students. The book has many sidebar stories too numerous to mention in a review. Radio Girl is a charming and very human story of how one small person mobilised an army of communicators to meet a national emergency. Radio Girl is most highly recommended.