By Petty Officer Marine Technician Andrew Campbell

IN 1940 there was naval action between Australia and Germany in Australian waters. This resulted in the loss of merchant seamen and ships, and indirectly the loss of an Australian naval vessel, HMAS Goorangai and its whole complement of 24 officers and sailors.

German Armed Merchant Raider Pinguin and its auxiliary Passat laid six minefields in Australia between 28 October and 7 November 1940.1

Passat minefields were laid in east and west Bass Strait.2 These minefields quickly claimed merchant ships Cambridge (British) at the eastern end of Bass Strait and the City of Rayville (American) at the

They both lost one sailor each whilst abandoning ship. The American sailor in City of Rayville was the first American sailor lost in WWII through hostilities.

The Pinguin was a successful German raider with an impressive record. Having sailed under Captain Ernst-Felix Kruder from 15 June 1940 to 8 May 1941 she accounted for 180,000 gross tons of shipping over 28 vessels.4 Kruder devised his mining plan after capturing the Norwegian oiler Storstad off Western Australia in transit from Borneo to Melbourne. The plan was to nearly simultaneously sow minefields near Australia’s south east cities and

The Castle Class trawlers were common. Their basic design was from the United Kingdom and they were not only efficient peacetime seagoing trawlers but suitable as auxiliary minesweepers in wartime. They were also used for these purposes by New Zealand and Canada.9 The trawlers varied a little in detail. Goorangai was 223 tons in displacement, had a single boiler with a single triple expansion engine, and a wartime armament fit of a 12 pounder gun, four depth charges, small arms and Oropesa sweep gear.10

The loss of HMAS Goorangai was due to a collision with MV Duntroon (pictured top right). Recent research into aspects of the collision has made use of now declassified material from the National Archive of Australia and the Australian War Memorial, along with other sources, which alters what was previously believed to have occurred.

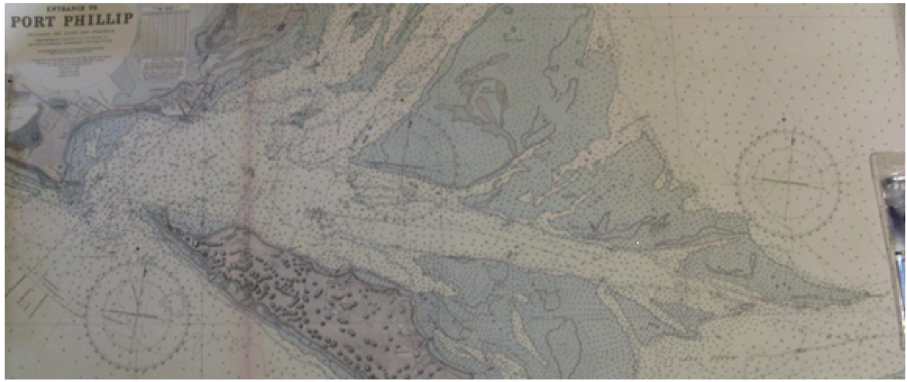

Minesweeping routine in November 1940 in Bass Strait required the ships to re-enter Port Phillip Bay for resupply. It was just after a resupply that HMAS Goorangai initially anchored off Queenscliff on the hot afternoon of 20 November 1940.11 At about 2000, with the cool change weather conditions, Goorangai began a short move to a more comfortable anchorage at Point Nepean near the Quarantine Station.12

At around 2030 the 10,400 ton MV Duntroon was transiting the South Channel on her way to Sydney from Perth via Melbourne carrying 65 passengers and general and perishable cargo.13 It struck Goorangai forward of the funnel on the port side and cut her in two14 while crossing the South Channel from Queenscliff at about 2045.15 Goorangai sank in less than a minute resulting in the drowning of her whole ship’s company.16

There were 13 eyewitnesses to the night time collision. These were present at the Port War Examination Signal Service located at Point Lonsdale; the Royal Australian Artillery station at Point Nepean; the Point Lonsdale Lighthouse keeper; a Port Phillip Pilot in an incoming Japanese merchant ship Kitano Maru, and the captain of Duntroon and his watch-keepers.17 From these accounts under cross examination during the Marine Board of Inquiry the true story is ascertained.

The weather at the time was Force 418 with a visibility of between 5 to 6 nautical miles.19 The tide was ¼ ebbing20 with an outward current of four to five knots.21 Duntroon displayed downward directed dimmed wartime navigation lights while Goorangai displayed bright harbour navigation lights.22 The Duntroon was travelling at 17 3/4 knots23 and the captain believed he was overtaking Goorangai but instead he was on an unchanging relative bearing24 (a collision course) and Goorangai was actually crossing Duntroon’s track from Duntroon’s starboard side.25

At a minute before impact the captain of Duntroon observed Goorangai’s port navigation light bearing 1 to 1.5 points off the starboard bow at distance 1.5 Nm26 and realised the true heading of Goorangai and the imminent collision.27 Goorangai had at the same time sighted the dimmed lighting of Duntroon’s presence and was using its Aldis lamp to alert Duntroon of its presence.28 Duntroon’s action was to turn to port and bring her engines to stop instead of a more logical turn to starboard or even stand on to pass astern of Goorangai.

The reason the captain of Duntroon gave for the turn to port was to give the other vessel a glancing blow on collision.29 The slow speed diesel engines of the Duntroon needed more than a minute to enact a stop and Duntroon still had way on forward when Duntroon’s life boats were launched which was two minutes after the collision.30 Witnesses reported hearing sound blasts varying in number between two and five31 and assumed them to be from Duntroon but the Duntroon captain initially said he made no sound signals.32 Duntroon did not engage its engines astern for a few minutes after the collision because the Captain said he did not wish to reverse over the Goorangai wreck or survivors.33 The engineering officer also commented that at the speed they were travelling many minutes were needed to obtain astern.34 The possibility of Goorangai sounding five blasts35 (asking Duntroon of her intention) was not raised in the inquiries.

After the collision Duntroon eventually stopped, put on all its upper-deck lighting and signalled to the Examination Service that a collision had occurred while two lifeboats were lowered to search for survivors.36 The Examination Service advised both the Royal Australian Engineers picket boat, SS Mars and the Queenscliff lifeboat,37 and they joined the search for survivors after delays due to Mars needing to raise steam,38 and the lifeboat running aground on the sandbar which had formed at the end of its launching rail39 at the end of Queenscliff pier.

After an hour of searching unsuccessfully for survivors the Duntroon lifeboats were retrieved and Duntroon40 returned to Williamstown to have her bow repaired.41

HMAS Goorangai was the first Royal Australian Navy (RAN) ship lost in WWII, the first RAN surface ship lost in wartime, and the first RAN surface ship lost with all hands.

Her crew were members of the RANR.42 Some of them such as the master (Commissioned Warrant Officer David McGregor) were former crewmen from her peacetime role as a trawler.43 The remainder of the crew were RANR many from Williamstown.44

Difficulties with bodily remains

The remains of just six of the 24 sailors killed were recovered from the wreck during salvage operations in the following months after the sinking.45 The five identified sailors were Ordinary Seaman Austin Carter (31), Chief Engine Room Artificer Charles Green (37), Able Seaman Norman Farquharson (21), Stoker 2nd Class Leslie Mainsbridge (20), and Leading Stoker John Moxey (38).46

Four of the sailors including the unidentified remains of a Goorangai sailor were buried at Williamstown47, one each were buried at Springvale48 and Cheltenham49 as requested by their Next of Kin.

One of the sailors’ bodies could not be identified.50 His remains were the last recovered and he was buried within 24 hours of discovery.51 These remains were rediscovered in an undefined and unmarked grave at Williamstown Cemetery in 2013.52

The unidentified remains were recovered two months after the collision. Although Leading Seaman Moxey was recovered and identified two days before,53 decomposition of the unidentified sailor had made it ‘impossible to identify.’54 Also the same sailor who identified four of the sailors wasn’t present to identify the unidentified sailor.55 There were 19 sailors bodies unrecovered varying in age from 17 to 46 of various heights and weights56. Unfortunately there was no attempt to record height, weight, build, blood type or estimate the age of the unidentified sailor.57 There was also no record of families of the 19 candidate sailors being informed of the recovery.58

The Office of Australian War Graves (OAWG) were unaware of the unidentified remains existence until they were informed in July 201359 and were provided with conclusive documentary evidence60 which was ultimately verified by the Department of Defence and Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA).61 Although modern methods such Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and Forensic Anthopological testing could now identify the sailor if families of the 19 could be found, DVA say it is against policy to exhume war grave remains.62 The unidentified sailor candidate identity could also be narrowed from the 19 possible sailors based on the location of the ship demolition at the time of discovery63 and the likely disposition of the ships company during its movement of anchorage. But because of the DVA policy the sailors’ identity will remain unknown. The unidentified sailor has now had his burial plot marked and the OAWG will now maintain the plot.

Navigation Hazard

Because the Goorangai wreck was inside the shipping transit zone, she was perceived as a navigation hazard and a quick method of clearance and salvage was determined as essential.64

The original salvage plan was to be a three phase evolution.65 The milestones for these were:

1. Recover bodies, depth charges and confidential books,

2.

3. Recover equipment such as the 12 pounder gun, minesweeping gear and any further bodies, then oxy-acetylene cut the hull, and

4.

5. Salvage or remove the hull. This phase was perceived as being beyond naval resources.

6.

After obtaining an estimate in money and time of 15000 pounds and six months66 to complete phase three, the Naval Board was reluctant to devote resources67 but the port authority required the wreck be removed as a matter of urgency because it represented a navigational hazard68 in the South Channel.

For phases one and two HMAS Beryl 11 was used as the diving platform.69 The salvage began three days after the collision. The delay was caused by inclement tide and weather conditions which would have made diving hazardous.70

The tidal conditions in that area of the bay would have hampered diving operations because of the constant strong tidal movements between inside Port Phillip Bay and Bass Strait. This would have reduced diving to be during ‘slack water’ a period of only 20 to 40 minutes per tide as the ebb and flood tides which can result in up to a seven knot tidal flow.71 The sand sea bed of the area would have also raised turbidity which would have reduced visibility.72

Many of the divers used were stokers from HMAS Cerberus.73 Their experience of fitting and oxy acetylene cutting was necessary to recover the gun and cut the wreck into liftable sections.

On the second day of diving the first sailor’s body was recovered74 also the first of four Type D* depth charges was recovered without incident.75 The second depth charge was accidently set to armed.76 This could have been an added disaster given that the pistol settings for these were to function at 50 or 80 feet77 and the depth of the wreck was 48 feet.78 This could have fired its 54kg TNT charge79 at the moment of the accidental setting. It would certainly have killed the divers and because of the close proximity of the other two depth charges would likely have sympathetically detonated a blast of 162kg of TNT. With that size of charge there would have likely have been damage and casualties to HMAS Beryl 11 as well.

There was then a delay of a few days while approval of disposing of the armed depth charge was sought. The method used was to dispose of the three remaining depth charges in-situ using a time expired charge from a Type H Mark 2 mine80, containing 145 kg of Amatol81 and with the three depth charges (3x54kg=162kg) the equivalent of a single charge of about 321kg of TNT. The resultant demolition (debris breakup and dispersal) were used by the explosive ordnance officer to justify an alternative to salvage and vary phase three to clear the navigation hazard by breaking up and dispersal of the wreck using explosives rather than raising and removing the wreck.82

After the depth charges were disposed of, the second, third and fourth bodies were recovered over three consecutive days.83

With the recovery of the 12 pounder gun, one depth charge, one mine sweeping wire, a dan buoy, a standard compass and a statement that the confidential papers are irretrievable,84 HMAS Beryl 11 was then withdrawn from diving operations as it was required to continue mine sweeping in Bass Strait.85

The revised phase three method was then submitted for formal approval by the naval board.86 The plan was to use six, time expired charges from Type H Mark 2 mines to open the bow and stern and then fold the hull flat on the sea bed. Smaller charges were planned to break up small projections.87 The number of charges used was increased to between 10 and 30 Type H Mark 2 mine charges (1450kg to 4350kg of Amatol) and the use of smaller charges were replaced by ‘wholesale blasting’ using double Type H Mark 2 charges.88 After sighting a 14 foot long shark a Type H Mark 2 charge was fired prior to each time divers entered the water.89 There were also two misfires of the Type H Mark 2 charges which were countermined using more Type H Mark 2 charges.90

On the second day of phase three (21 January 1941) the fifth body was recovered.91 The following day, diving was suspended due to the motor dive boat supplied by the armament depot at Swan Island having engine failure. While the disabled boat was attached to one of the wreck mooring lines a seaweed clump rose from the wreck with a distinctive odour which alerted the boat occupants of a corpse entangled in the centre of the seaweed.92 Because of the tide and lack of motive power on the boat the corpse drifted through the Rip on the ebb tide and wasn’t recovered.93 Two days later the last (and unidentified) body was recovered.

Investigation

The Court of Marine Inquiry found both ships to be at fault for the collision.94

The person navigating Goorangai was not found to be in default of the Navigation Act at the time, whereas the captain of Duntroon was found to be in default in the following ways:

a. Not keeping proper lookout;

b.

c. Failing to watch compass bearing of the other vessel, and;

d.

e. Not reducing speed of his ship earlier when approaching a situation which was obviously dangerous.95

f.

As a result the captain of Duntroon was asked to ‘show reason’ to retain his master’s certificate and Port Phillip Bay pilot exemption.

During the Marine Board of Inquiry there was an accusation of military eyewitness accounts colluding96 even though there were minor differences in logged accounts and they were consistent with the Point Lonsdale lighthouse keeper account and the accounts given the day after the collision.97 The military eyewitnesses were required to give evidence of occurrences with times using no notes or logs and later checked against their logs.98

In contrast the Duntroon log of the collision was written up the next day after the collision in the Melbourne Steamship Company office in King Street, Melbourne using transposed times from the engine room chalk board, engine room log and the first mate’s log99 (the first mate wasn’t on the bridge until seconds before the collision).100 The log was presented on the last day of the inquiry after all other evidence had been presented. Duntroon’s chart was never submitted as evidence.

Although the Marine Board of Inquiry was reported in the press, the detailed report was classified SECRET.101 The charges against Duntroon were defended by legal representatives of the Duntroon captain and the Duntroon owner at the ‘show reason’ inquiry.102 The transcripts of this haven’t been located but the outcomes were reported in the press.103 Unlike the earlier Marine Board of Inquiry the Navy wasn’t legally represented at the Coronial Inquiry104 and didn’t appear to be represented at the ‘show reason’ inquiry.105 This allowed a one-sided more favourable outcome by ‘cherry picking’ witnesses from the original Marine Board of Inquiry.

As there was no cross examination, the captain of the Duntroon was able to vary his version of events in both the ‘show reason’ inquiry and again at the Coronial Inquiry.106 To defend the charges the legal representative stated: ‘The captain decided not to continue with submission (as) there was no case to answer. It was not decided that anything in the nature of a scotch verdict (not proven) should be given.’

It is probable that the charges would have been difficult to defend because a logical argument would have arrived at the same result as the earlier Marine Board of Inquiry, so the charges seemed to have not been addressed.107 Instead the perceived poor positioning of side navigation lights aboard Goorangai was identified as the main cause of the collision.108 This was even though a Navy assessment after the Marine Board of Inquiry considered the obscuration theory so unlikely that no modifications to the existing system were recommended for Goorangai’s sister ships109 but a completely different design was installed later. Because the wreck of Goorangai had by the time of the inquiry, been demolished110 the obscuration of navigation lights was determined through the invalid engineering practice of scaling overall ship drawings111 and guessing on sizes arriving at a port side horizontal obscuration of 20 40’ from the midships heading.112

Other defences which presented during the Marine Board of Inquiry included the possibility of incorrect lights switching or a dynamo (electrical generator) failure.113 Even though eyewitness accounts didn’t support this scenario, the issue was not raised further during the ‘show reason’ or Coronial Inquiries. The result of the ‘show reason’ inquiry was that the captain of Duntroon was exonerated based on legal defence of a ‘Scotch Verdict’.114

This led to a common story that didn’t reflect the true details of the collision. It was made easier to espouse an inaccurate story using wartime restrictions on the inquiry documents being security classified together with there being no surviving victims from one ship – HMAS Goorangai. The result was that previous history was friendlier to the surviving vessel and her crew.

The incorrect common story was that MV Duntroon while sailing through South Channel of Port Phillip Bay at night with full navigation lights showing, struck HMAS Goorangai with no navigation lights showing while in transit from Queenscliff to Portsea. The collision resulted in HMAS Goorangai sinking with all hands. MV Duntroon continued to sail to Sydney without stopping as she was transporting troops for the war effort. The common story could be read from many legitimate sources such as Heritage Victoria,115 and so has been repeated by museums and others.116 Further, the details such as the number of sailors’ bodies recovered from HMAS Goorangai varied from five to seven with sometimes the claim that one was buried at sea.117

The official story covering the Goorangai story is sparse and covering just a few sentences with no detail about the collision118 but there is discussion regarding the exploits of Pinguin and Storstad.119

Aftermath

Duntroon was involved in another collision in November 1943, this time resulting in the loss of USS Perkins and four sailors.120 Duntroon with the same captain continued operation throughout the war as a troop carrier and following the war was used to repatriate POWs and to ferry personnel in the Japanese occupational force. The ship was handed back to her owners in 1949.

German Merchant Raider Pinguin continued its raiding and Passat de-commissioned and was renamed back to Storstad but continued as a supply ship for raiders. Other raiders Kormoran and Komet were resupplied by Pinguin off Kerguelen Island before attempting to get back to Germany.121 Pinguin came to a fiery end with a shoot out against HMS Cornwall. Pinguin’s WWI-era 6-inch guns were no match for the modern 8-inch guns of Cornwall.122

A German perspective of the Goorangai incidentwas described briefly by Pinguin’s surviving second officer, medical officers and chief quartermaster who collaborated in a book where they incorrectly claim one of their mines claimed an Australian minesweeper in the roads off Port Phillip, presumably referring to Goorangai.123

The author

Petty Officer Marine Technician Andrew Campbell has served on minor war vessels and in mine warfare billets. He has been a reservist for over 30 years. His civilian career with the Department of Defence began as an apprentice at Williamstown Naval Dockyard and ended 38 years later as an Explosive Ordnance Specialist Technician and Senior Technical Advisor for a Direct Fire Support Weapon project. He has engineering and explosive ordnance qualifications along with a Master 5 certificate.

References

1. Wikipedia, German auxiliary cruiser Penguin, 12 August 2013, viewed 9 September 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_auxiliary_cruiser_Pinguin

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Brenneche, 1954, Ghost Cruiser HK33, William Kimber Press, London p.208.

5. Ibid p.114.

6. Ibid p.119.

7. Wikipedia, HMAS Beryl II, 21 March 2013, viewed 9 September 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAS_Beryl_II

8. Do You Remember Sydney’s Steam Trawlers, viewed 7 November 2013, http://www.afloat.com.au/afloat-magazine/2008/november-2008/Do_you_remember_Sydneys_Steam_Trawlers

9. Michael Burgess, 1981, The Royal New Zealand Navy, Burgess Media Services Ltd,

10. Wikipedia, HMAS Goorangai, viewed 20 April 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAS_Goorangai

11. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) at p.107. and p.122.

12. Ibid. p.130.

13. Ibid. p.6.

14. Ibid. p.227.

15. Ibid. p.440.

16. Ibid. p.446. and Department of Navy message M596 dated 21 November 1940

17. Ibid. p.6. to p.267.

18. Ibid. p.428. and 1940, Weather Map, The Argus, 21 November 1940, p.14.

19. Ibid. p.418.

20. Ibid. p.230. and 1940, Weather Map, The Argus, 21 November 1940, p.14.

21. Ibid. p.230.

22. Ibid. p.6. to p.267.

23. Ibid. p.12. to p.15.

24. Ibid. p.8.

25. Ibid. p.9.

26. Ibid. p.12. to p.15. and Charges Not Sustained, The Argus, 7 January 1941, p.2, article. and Inquisition Held at Court House Geelong on 7 Apr 1941 Before N. J. Haynes esq JP Deputy Coroner.

27. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) p.13.

28. Ibid. p.222.

29. Ibid. p.15.

30. Ibid. p.52.

31. Ibid. p.6. to p.267.

32. Ibid. p.12.

33. Ibid. p.15.

34. Ibid. p.367. to p.372A.

35. International Regulation for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 Part D – Sound and Light Signals Rule 34 (d)

36. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) p.52.

37. AMF Military Board Report on Collision HMAS Goorangai and MV Duntroon on 20 November 1940 file 59/401/53 refers. and Navy Board – Board of Inquiry – Sinking of HMAS “Goorangai” 21 November 1940. p. 4.

38. Board of Inquiry assembled at Queenscliff at 1145 Friday 22 November 1940. p.10

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) at p.47.

42. Ibid. p.478.

43. Ibid. p.73.

44. Services Records of: PM846, PM2509, PM2485, S999, W436, PM2755, W1437, W1433, W1567, PM2642, PM2748, PM2541, PM1322, PM2218, W1588, PM1863, H1298, PM2920.

45. Report, Lieutenant Commander Ronald B. Clark Hutchinson, Salvage and Dispersal of the Wreck of HMAS ‘Goorangai’, 14 January 1941.

46. Service Records of: W1433, PM2642, PM2748, PM1863.

47. Personal Correspondence Campbell / Brewer – Commonwealth War Graves Commission dated 11 June 2013.

48. Personal Correspondence Campbell / Brewer – Commonwealth War Graves Commission dated 18 June 2013.

49. Personal Correspondence Campbell / Brewer – Commonwealth War Graves Commission dated 19 June 2013.

50. Signal, MY0401Z/21.

51. Williamstown Burial Register, p.458. and p.457.

52. Personal Correspondence Campbell / Brewer – Commonwealth War Graves Commission dated 11 June 2013.

53. Report, Lieutenant Commander Ronald B. Clark Hutchinson, Salvage and Dispersal of the Wreck of HMAS ‘Goorangai’, 14 January 1941.

54. Inquisition Held at Court House Geelong on 7 Apr 1941 Before N. J. Haynes esq JP Deputy Coroner.

55. Ibid.

56. Services Records of: PM846, PM2509, PM2485, S999, W436, PM2755, W1437, W1433, W1567, PM2642, PM2748, PM2541, PM1322, PM2218, W1588, PM1863, H1298, PM2920 and 1940, Death Notice (Hack), The Age, 22 November 1940

57. Inquisition Held at Court House Geelong on 7 Apr 1941 Before N. J. Haynes esq JP Deputy Coroner.

58. Australian National Archive compiled file on recovered remains HMAS Goorangai 674/203/178

59. Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Naval Board, NRD (W), dated 24 December 1940

60. E-mail, Campbell to DVA, Australian War Graves, dated 11 June 2013.

61. Report, enclosed in E-mail Army Headquarters to Campbell, Goorangai Report dated 29 Nov. 2013.

62. E-mail, DVA to Campbell, Australian War Graves, dated 7 June 2013

63. Report, Lieutenant Commander Ronald B. Clark Hutchinson, Salvage and Dispersal of the Wreck of HMAS ‘Goorangai’, 14 January 1941.

64. Letter, Ports and Harbours / District Naval Officer – Victoria, Letter 039977, file 2026/14/164.

65. Report, HMAS ‘Goorangai’ – Salvage and Other Arrangements from District Naval Officer to Naval Board dated 28 November 1940, file 2026/14/164.

66. Quotation, for HMAS Goorangai salvage costs from United Shipping Services dated 29 November 1940.

67. Letter, HMAS Goorangai Salvage from Navy Office to District Naval Officer – Victoria dated 7 December 1940, Letter 03997, file C182/4/42

68. File Note, dated 11 December 1940, file C182/4/42

69. Message, from Flinders Naval Base to District Naval Officer – Victoria, dated 21 November 1940 and Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to HMAS Beryl 11, dated 13 December 1940, file 2026/14/164

70. Message (x2), from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Flinders Naval Base, dated 22 November 1940

71. Chart, Commonwealth of Australia, The Rip, Chart Aus 144, Note – Non Tidal Changes at Sea Level and Tidal Streams, dated 2013 and Chart, Commonwealth of Australia, Entrance to Port Phillip, Chart BA 2747, dated 1936 to 1952

72. Report, Lieutenant Commander Ronald B. Clark Hutchinson, Report on the Dispersal of the Wreck of HMAS Goorangai, dated 14 January 1941

73. Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Naval Board, dated 24 November 1940

74. Message, from Flinders Naval Base to District Naval Officer – Victoria, dated 21 November 1940

75. Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Flinders Naval Base – Swan Island, dated 29 November 1940

76. Ibid.

77. British ASW Weapons, viewed 18 January 2014, http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WAMBR_ASW.htm

78. Message, from HMAS Beryl 11 to Flinders Naval Base dated 23 November 1940 and Message, from XDO to Flinders Naval Depot 30 January 1940

79. British ASW Weapons, viewed 18 January 2014, http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WAMBR_ASW.htm

80. Message, from ACNS to CNS dated 30 November 1940 and Minute ‘Goorangai’ from Director of Ordnance Torpedoes and Mines to Head of ‘N’, dated 4 December 1940

81. British Mines, viewed 18 January 2014, http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WAMBR_Mines.htm

82. Minute ‘Goorangai’ from Director of Ordnance Torpedoes and Mines to Head of ‘N’, dated 4 December 1940

83. Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Naval Board, dated 3 December 1940 and Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Naval Board, dated 4 December 1940 and Message, from Senior Naval Officer – Victoria to Naval Board, dated 5 December 1940

84. Report, Recovery of Gear from HMAS “Goorangai”, dated 16 December 1940, file 2026/4/164

85. Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to HMAS Beryl 11, dated 13 December 1940, file 2026/14/164

86. Report, HMAS Goorangai – Destruction of Wreck for Purpose of Destroying Goorangai, dated 1 January 1941, file 2026/14/164

87. Ibid.

88. Report, Lieutenant Commander Ronald B. Clark Hutchinson, Report on the Dispersal of the Wreck of HMAS Goorangai, dated 14 January 1941

89. Ibid.

90. Ibid.

91. Ibid.

92. Message, from District Naval Officer – Victoria to Naval Board, dated 22 January 1941

93. Report, Lieutenant Commander Ronald B. Clark Hutchinson, Report on the Dispersal of the Wreck of HMAS Goorangai, dated 14 January 1941

94. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) at p.447.

95. Ibid.

96. Ibid. p.458.

97. Report, Navy Board of Enquiry-Sinking of HMAS “Goorangai”, 22 November 1940, file 182/4/42.

98. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) at p.438.

99. Ibid. p.439.

100. Ibid. p.36.

101. Ibid.

102. 1940, Charge Not Sustained, The Argus, 7 January 1941, p.2.

103. Ibid.

104. Inquisition Held at Court House Geelong on 7 Apr 1941 Before N. J. Haynes esq JP Deputy Coroner.

105. Charge Not Sustained, The Argus, 7 January 1941, p.2, article.

106. Ibid. p.2, article. and Inquisition Held at Court House Geelong on 7 Apr 1941 Before N. J. Haynes esq JP Deputy Coroner. and Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) at p.6 to p.19.

107. Charge Not Sustained, The Argus, 7 January 1941, p.2, article.

108. Ibid

109. Report, Report on Collision HMAS Goorangai and MV Duntroon 20 November 1940, 8 January 1940, file 59/401/53.

110. Report, HMAS ‘Goorangai’ – Salvage and Other Arrangements from District Naval Officer to Naval Board dated 28 November 1940, file 2026/14/164.

111. Drawing Standard AS1100 CZ1.

112. Commonwealth Court of Marine Inquiry – In the matter of: An Inquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Collision Between the MV Duntroon and HMAS Goorangai off Queenscliff on 20th November 1940, (1940) at p.432.

113. Ibid.p.464.

114. 1940, Charges Not Sustained, The Argus, 7 January 1941, p.2, article.

115. Heritage Victoria website viewed 25 June 2013, http://vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au/shipwrecks/heritage/294

116. Monument Australia, viewed 20 April 2014, http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/conflict/ww2/display/33211-h.m.a.s.-goorangai-h.m.a.t.-duntroon-collision , Maritime Archeaology Association Victoria, viewed 26 June 2013, http://home.vicnet.net.au/~maav/goorangai.htm .

117. RAN Seatalk Spring 2009, viewed 20 April 2014, http://intranet.defence.gov.au/navyweb/sites/NGN/docs/Sea_Talk_2009-spring.pdf . Goorangai (Royal Australian Naval Professional Studies Program) 1 (1). November 2004. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

118. Gill, G. Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. p.275.

119. Ibid p.270 to p.276.

120. Wikipedia, HMAS Duntroon, 31 October 2013, viewed 9 November 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAS_Duntroon

121. Brenneche, Jochen 1954, Ghost Cruiser HK33, William Kimber Press, London

122. Ibid.

123. Ibid p.135

a very interesting article on a little known ship of the royal australian navy