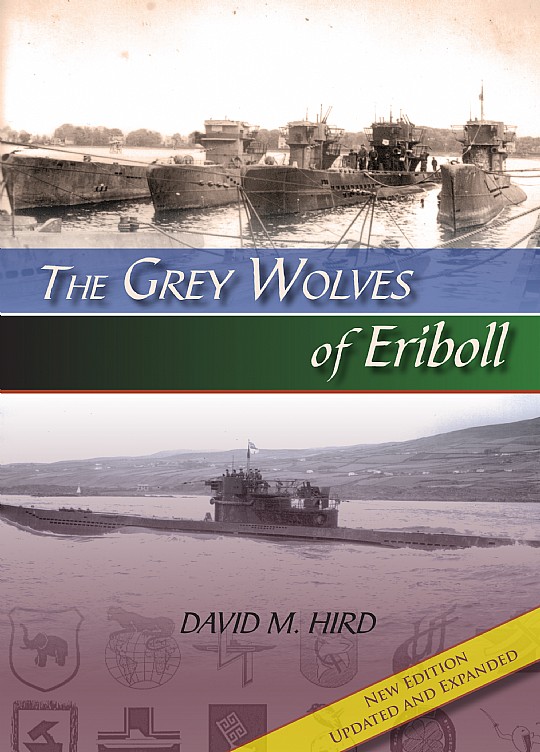

The Grey Wolves of Eriboll. By David M. Hird, Whittles Publishing, Dunbeath, second edition 2018.

Reviewed by John Johnston

ONE impressive image from the Second World War is of Admiral Sir Max Horton, commander in chief, Western Approaches taking the surrender of the German U-boat flotilla at Lisahally on Lough Foyle, near Londonderry in Northern Ireland on 14 May 1945. The pictures and accompanying press and newsreel reports of the event might nowadays be described as ‘fake news’ because the boats had already surrendered at Loch Eriboll, near Cape Wrath on the north coast of Scotland.

The public in the Allied countries, however, needed to see that the surrender had actually taken place. Eight boats were therefore handed over formally in Lough Foyle, with the wide expanse of the lough providing an imposing backdrop for the ceremony. The location was symbolic: Derry had been the Allies’ operations centre in the Battle of the Atlantic, while the waters off the ambivalently neutral Irish state had been the principal hunting ground for the German Wolf Packs during the battle.

By the end of May, all of the U-boats that had been operational had surrendered or had been scuttled. The surrendered boats had been moved under escort to Loch Alsh, where most of the crews were disembarked and transferred to prisoner of war cages, and then to Loch Ryan to await the decision of the Allies on their fate. That was agreed in August at Potsdam, and over the autumn thirty boats were divided equally between the Americans, the Soviets, and the British, with the remaining eighty-six boats being sunk – or more often, floundering – in the Atlantic in December 1945.

In itself, this story might seem no more than a footnote to the much grander tale, but setting up the operation to receive the surrendering boats and to secure them was a prodigious logistic task. Coastal Command and Fleet Air Arm patrols, for instance, had to identify and make contact with surrendering boats, while British and Canadian ships had to locate the boats and escort them into Loch Eriboll and then to Loch Alsh and Loch Ryan.

David Hird’s success is bringing these stories together and adding to them with extracts from official documents and newspaper reports, with participants’ accounts, some from the time and some from memory, with histories of the RN and RCN ships and of the U-boats and other vessels and with short biographies of personalities. The result is a fascinating account of a little known operation and a treasure trove of vignettes that are as attractive for the general reader as they are for the specialist.

The latter, however, will find much to ponder in the story. By reproducing documents, letters, and newspaper reports on conditions aboard a U-boat, for instance, Hird reveals the privations the crew experienced and he notes the disbelief of Allied officers that their sailors would tolerate such conditions or be able to function in them. Similarly, the problems which he describes the Allies facing in preparing for the surrender of the U-boat flotilla are no different to those that are faced today in disarming factions as part of peace support operations. There are lessons to be drawn from the story of Loch Eriboll, and this book deserves to be on staff officers’ reading lists as much as it does on that of anyone interested in naval history.