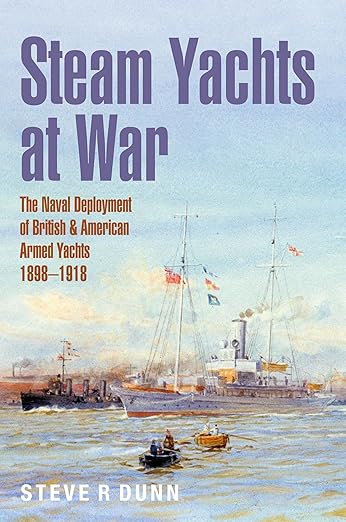

Steam Yachts at War. By Steve R Dunn. Seaforth Publishing, 2024

Reviewed by Mike Carlton

In exile in Europe in the mid-17th century, presumably with time on his hands, King Charles II of England was mightily impressed by the fast and elegant sailing craft that the Dutch called jachten. On his restoration to the English throne the citizens of Amsterdam presented him with one, a luxurious 60-footer with a crew of twenty, named the Mary. Thus, the word yacht entered the English language.

In 1661, at the helm of Katherine, the first British built yacht, Charles raced and beat Anne, owned by his brother the Duke of York, over 40 miles on the Thames. A sport was born.

Fast forward a couple of centuries to the Gilded Age of high Edwardian opulence: on each side of the Atlantic a yacht – sail or steam or both – was the ultimate status symbol for royalty of all sorts, for the British aristocracy, for the fabulously wealthy magnates of Europe and the United States. They vied with each other to throw their fortunes at building and owning vessels of the utmost style, speed and comfort, each new creation more dazzling than the last. As the financier J.P.Morgan famously remarked, “ Anyone who has to ask about the annual upkeep of a yacht can’t afford one.”

Mr Charles W. Lawson of Boston, known as the Copper King, commissioned the steam yacht Dreamer in 1900, with The New York Times rhapsodizing that “the deck boudoir is finished in white, with old rose coloured upholstery, while green is the prevailing colour in the oak rooms, the frieze panels and sofa…Mrs Lawson’s room is finished in ivory white, the panels and bed hangings being of pink silk with linen-lace applique . . . ”

The Lawsons were by no means unique. Even to the layman’s eye the yachts were quite breathtakingly beautiful with their raked masts and funnels, polished timbers and dazzling brass, their gleaming hulls with flared clipper bows as sharp as steak knives. Ever anxious to outdo his English cousins, in 1889 the German Kaiser Wilhelm II turned up in his yacht Hohenzollern for a review of the Royal Navy at Spithead, sporting the uniform of a British Admiral of the Fleet. The captain of the ironclad HMS Inflexible recalled that he’d “had the honour of receiving a hearty shake from the unmailed fist, before it had become stained with innocent blood, and before the blasphemous hypocrite – prince of spies and father of lies – had been found out and his villainous character exposed.”

Snobbery was a large part of it. The eye-wateringly wealthy Scottish tea tycoon Sir Thomas Lipton owned a series of racing yachts, all named Shamrock, in which he gallantly proceeded to lose five successive Americas Cups, from 1899 to 1930. In his day he was the most famous yachtsman in the world, but he had been born in a Glasgow tenement, was sneeringly referred to by the upper crust as “the King’s grocer,” and was not admitted to the ultra-snooty Royal Yacht Squadron until shortly before his death in 1931.

As ever with the ultra-wealthy, eccentricity was unremarkable, but one or two yacht owners were barking mad. The New York banker McEvers Bayard Brown, spurned by a lover, took his yacht Valfreya off to the little port of Brightlingsea in Britain in 1890 where he stayed for some 36 years. He spent around $4,000 a month on her upkeep, with steam up day and night, the crew ready to sail at a moment’s notice, but he never put to sea again. Not once. In his obituary, Time magazine reported that “Mr Brown almost daily caused his chef to heat large pans of gold and silver coins as hot as possible on the galley stove. The beggars of Brightlingsea, anxious to humour his whims, appeared in rowboats and caught the coins in their bare hands as Mr Brown hurled the bits of gold and silver overboard with a shovel. If the beggars attempted to use gloves he hurled boiling water upon them instead. When the moon was full he hurled nothing at all…occasionally he wrapped lumps of coal in £100 notes and heaved them at submissive heads. Countless eyewitnesses testify to his evident delight in scorched palms and bruised flesh.”

These and a feast of other delicious details are studded through Steve R.Dunn’s book. Its full title is Steam Yachts at War, the Naval Deployment of British & American Armed Yachts 1898-1918, and there is indeed plenty of war stuff if you want it.

The Americans started the fashion for sending rich men’s yachts to conflict when the United States Navy realised, to its dismay, that it did not have enough small craft to blockade Cuba during the Spanish-American war of 1898. The press baron William Randolph Hearst – who had virtually started the war himself as a circulation winner for his newspapers – let them have his boat, Buccaneer. Others were simply commandeered, to the fury of their owners.

Much the same happened again in World War 1, with English aristocrats and tycoons patriotically offering up their craft, and often their crews, to the Admiralty. Others had to be dragged to the fray. The tight-fisted 11th Duke of Bedford complained bitterly to the First Lord, Winston Churchill that his yacht Sapphire was about to be taken from him: “…if I like to voluntarily make a magnanimous offer of my yacht I shall not only avoid requisition and escape a heavy pecuniary penalty but receive a handsome douceur in cash…” he snapped.

The war service of all these craft was wide and varied. Some were coastal patrol vessels, some were convoy escorts with a popgun mounted on the fo’c’sle, a good few were actively in the fight. Bedford’s yacht, commissioned as HMS Sapphire II and armed with a 4-inch gun, fought a depth charge battle with a U-boat in the Mediterranean. Many were lost to U-boats or to mines.

Steve Dunn’s research is prodigious and endlessly rewarding. The photographs and diagrams are superb. This is one of those books you approach like a box of luxury chocolates, plucking out the treasures and savouring each bite.