Regional Security, Sovereignty and Solomon Islands: A Broken Pacific Defence Compact?

By Dr Richard Herr, OAM*

Introduction

The China–Solomon Islands security agreement has raised many questions, from why the Solomons would enter into such an uneven pact to how Australia could fail to prevent it. The most critical question, however, is: will the pact shake the established foundations of regional security?

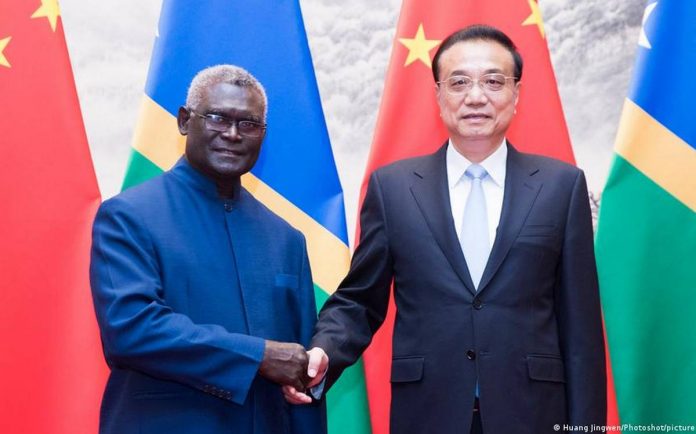

Immediate reactions from almost everywhere but Beijing and Honiara suggest the answer is that it is a game changer.[1] If so, what game has it changed? Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare denies the pact has any external security implication, expressing outrage at criticism as an insult to the Solomons as a sovereign state.[2] China has predictably labelled Western criticism as displaying a ‘hegemonic and colonialist mentality’.[3] Despite these denials, the agreement has changed geostrategic expectations and so given substance to a fear expressed by the region’s peak political body, the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) that the new ‘complex geo-political environment’ of the Indo-Pacific will make the Pacific Islands region a cat’s paw in great power rivalry.[4]

In choosing ‘national interest’ over longstanding obligations to the region, Sogavare has exposed a weakness in the region’s collective security architecture, raising questions as to its continuing effectiveness. Former PIF Secretary General Dame Meg Taylor argued several years ago that the new geopolitical environment presented ‘greater options for financing and development … through the increased competition in our region’.[5] Her assessment that there could be financial advantage to regional states in leveraging heightened external security interest for aid has frequently been shared by some analysts who are quick to claim that any erosion of Western security interests is a consequence of neglect and inadequate aid. However, Dame Meg later added a rider regarding the temptation to trade in security access. She pointed out that there was always a price to be paid by the small states participating in such an auction.[6]

Small states commercialising sovereignty is scarcely novel or limited to the Pacific. Virtually all microstates engage in some aspect of selling sovereignty to make ends meet. Flags of convenience, special gambling zones, tax havens, selling passports and the like are common ways in which small states with limited natural resources have marketed their sovereignty.[7] So long as these activities do not destabilise local order or threaten the core interests of more powerful neighbours, they tend to be overlooked. However, trading in security access by its very nature threatens another country’s security interests, including its defence posture. In accepting the Chinese security initiative, the Solomons has deliberately created real consequences for Australian defence.[8] But why? What was the quid pro quo?

Significantly, the security agreement does not contain an aid provision. Moreover, it was drafted even while Australian and regional security assistance was in the Solomons providing the security Sogavare requested. One contributing influence appears to be tunnel vision of the Solomons Government regarding the role of defence in regional security. Pacific Islands security has been overwhelmingly based on the primacy of human security rather than on traditional physical security based in self-defence. The bias in the Pacific’s security orientation is highlighted by contrasting it with the role that defence plays in the Caribbean island microstates’ approach to security. The comparison draws out the difficulties Australia will face if it attempts to cultivate a better regional understanding of the defence consequences of trading in security access. It is difficult to discuss defence sensibly when there is no-one speaking the same language at the other end of the telephone.

Development assistance as the currency of Pacific regional security

The concept self-defence is an uncomfortable metric for measuring national security in the Pacific Islands region. Indeed, very few countries in the region provide directly for self-defence, at least as traditionally defined. The absence of national self-defence infrastructure in the Pacific Islands region stretches back to security decisions embraced by both the colonisers and the colonised at the cusp of independence. A shared belief was that there was no need for the microstates to invest scarce resources in national self-defence. This perspective was based on several mutual (or at least not seriously challenged) convictions at the time of independence. These were the absence of perceived external threat; pressing civilian development priorities; and the risks that a military might pose to democratic governance. Moreover, as nearly half today’s regional states had been trust territories within the United Nations system, there was an acceptance of international protection. Other factors included Western dominance across the region limiting the risks of inter-colonial tensions, and remoteness from Asian theatres of strategic rivalry. Significantly, because decolonisation was essentially benign, there were no wars of national liberation to create local militias that could morph later into national defence forces. The only two regional microstates with a military, Fiji and Tonga, had these prior to independence.

In retrospect, it is puzzling that the decolonising powers left without directly and formally guaranteeing the security of their former territories. There are no mutual security treaties between any regional state and its former metropole but there are some other arrangements that have security implications. The US has compacts of free association with three former territories – the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Palau. New Zealand maintains a similar relationship with two former dependent territories – the Cook Islands and Niue. These arrangements create some non-reciprocal defence obligations, although it is not clear that these are obligatory or even that the island state could initiate the implied defence assistance. A partial exception emerged in 2017. As part of the disengagement of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) from Solomon Islands, Australia and the Solomons government signed a non-reciprocal treaty providing for the Solomons to call on Australia and other RAMSI contributors to return to provide domestic security at the request of the Solomons.[9]

Unsurprisingly, given the absence of indigenous military forces in the region, the Pacific microstates have made no preparation to assure their physical security collectively through any mutual self-defence arrangements. Non-traditional security, however, is a different matter. The Pacific Islands region has perhaps the most robust ecology of regional agencies in the developing world. The PIF was established in 1971 in part to enable collective action by newly independent states to oppose French nuclear testing in the region on environmental grounds.[10] Australia and New Zealand were included as founding members, recognising the potential value of their diplomatic and military capacity.

Today there are several agreements through the agency of the PIF intended to pursue broad non-traditional security objectives, particularly regarding climate change. The most important of these are the 2000 Biketawa Declaration[11] (a framework for coordinating response to regional crises) and the 2018 Boe Declaration[12](or ‘Biketawa plus’, for a more comprehensive view of human security). Other regional bodies have contributed similarly within their own mandates for protecting the non-traditional security needs of the region’s people. These have culminated now in a sweeping aspirational claim by PIF member states for stewardship of the Pacific Ocean through the multi-decade Blue Pacific strategy.[13]

The Pacific Islands Regional Security Community Concept

A key feature of contemporary Pacific Islands national security is the way it has become bound up in the fabric of regional ties and relations. However, the regional security architecture that has evolved can scarcely be described as designed. It is based on tacit expectations and the language of circumlocution to avoid being explicit. Karl Deutsch’s concept of a ‘security community’ is the best descriptor for what emerged.[14] A core element of Deutsch’s concept is that the regional system constitutes a community with shared values. This has developed in breadth and depth since 1947, when the first regional body, the South Pacific Commission (SPC), was established. The 1971 creation of the South Pacific Islands Forum (now PIF) as a peak political body demonstrated the extent to which its members shared hopes and aspirations. Indeed, the SPC changed its name to the Pacific Community, in part to reflect this reality. The second element of the Deutsch formulation has been demonstrated by experience. The member states have maintained such intra-regional harmony that violent conflict between members has never occurred and remains almost unthinkable.

The basis of this unstated compact has been that the region’s security and that of virtually all its members would be guaranteed by the international community, with disputes settled through judicial processes or resolved by diplomacy. The physical security of the region would be underwritten by its Western sponsors, primarily Australia, New Zealand and the United States acting individually or collectively under the ANZUS Treaty but also at times Britain and France, the only extra-regional states with defence capacity in the region. To win regional states’ acceptance of the Western defence agenda, these ‘traditional friends’ of the region would contribute to domestic stability in the region through both bilateral and multilateral development assistance.

Two events helped to give some clarity to the contours of the regional security community concept in the decade or so after the first wave of independence. The establishment of diplomatic relations between Tonga and the Soviet Union in 1976 was alleged to include an aid component that had not been provided by Western sources. The ANZUS allies reacted by deliberately seeking to enhance the security community sentiment in the region. Their response had three elements. The first was that Australia and New Zealand should take point regionally for alliance security interests. Secondly, aid was consciously linked to security by agreeing that resources should be devoted to the development needs of the region, to obviate openings for outside challenges. Thirdly, regional solidarity should be promoted to minimise any tendency towards ‘adventurism’ by individual states, recognising that alliance security would be seriously compromised if the USSR were to secure even one satellite state in the region.[15]

The second major perceived challenge stemmed from the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III) changes to the law of the sea. This expanded the jurisdiction of the Pacific microstates to an extent completely beyond their own resources to defend. They had to rely on their own regional mechanisms embedded in UNCLOS III in order to protect their interests. Unfortunately the US was not prepared to accept all the new rules, especially those related to the primary resource the islands expected to exploit – highly migratory tuna. UNCLOS III also served as a catalyst for Soviet interest in deep-sea minerals research. This and a fisheries agreement with Kiribati in 1985 suggested that the USSR might be seeking strategic access to the region. The 1985 South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC) Treaty served to exclude Moscow from regional deep-sea exploration. The ANZUS states filled the void by funding the Soviet oceanographic aid projects that had provoked the treaty. The US moved also to resolve its fisheries dispute with the region by negotiating the 1988 South Pacific Tuna Treaty, which conceded coastal state jurisdiction without ratifying UNCLOS III. The treaty also provided US aid and enforcement assistance to the regional states.[16]

Thus, despite occasions of twisting the kangaroo’s tail, tweaking the kiwi’s beak or pulling Uncle Sam’s beard ritually to get Western attention, the Pacific Islands states maintained the general characteristics of a Western-aligned security community at least until recent events in Solomon Islands.

Caribbean security and self-defence

One critical difference between microstate security in the Caribbean and that in the Pacific is the centrality of a self-defence infrastructure in the Caribbean. Only two of the 13 microstate members of the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS) caucus at the UN have defence establishments.[17] And, of these, only Fiji (population 900,000) has a significant military force. That the other state, Tonga (100,000), has a defence force is explained in part by its being the region’s only monarchy, with the king’s authority over royal guards and the militia being included in the Constitution of 1875.[18] More than half of the nine Caribbean island microstates have military establishments to provide some capacity for national self-defence. This distribution of forces is not entirely related to population. As shown in Table 1, two of the Caribbean island microstates – Antigua and Barbuda, and Saint Kitts and Nevis – have smaller populations than Tonga’s. Moreover, the second smallest of the regional states, Dominica, also maintained a national defence force until 1981.

Table 1: National military establishments

| Country | Military | Population | Area (km2) |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Royal Antigua and Barbuda Defence Force | 96,286 | 442 |

| The Bahamas | Royal Bahamas Defence Force | 385,637 | 13,943 |

| Barbados | Barbados Defence Force | 286,641 | 430 |

| Dominica | N/A | 71,625 | 751 |

| Grenada | N/A | 111,454 | 344 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | Saint Kitts and Nevis Defence Force | 52,441 | 261 |

| Saint Lucia | N/A | 181,889 | 539 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | N/A | 110,211 | 389 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Trinidad and Tobago Defence Force | 1,389,843 | 5,130 |

Interestingly, in light of one of the arguments against establishing national defence services in the Pacific, Dominica’s decision to disband its military only three years after independence was motivated largely by a failed army coup. However, the country’s compensating response illustrated another significant difference from the Pacific. Dominica was able to replace the loss of a national defence force by joining a regional mutual defence pact which gave it rights to call upon shared military resources from its regional neighbours for its physical defence.

In 1982, Dominica joined two other regional states without national self-defence forces – Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines – in a mutual defence arrangement with two neighbours that did have military establishments – Antigua and Barbuda, and Barbados. This 1982 treaty established, with US support but without US membership, the Regional Security System (RSS) to provide for the defence of the eastern Caribbean.[19] Saint Kitts and Nevis joined on independence in 1983, adding its defence force to the RSS. Grenada entered the RSS in 1985 without a national military, after recovering from the upheavals leading to the US intervention in 1983.

Thus, since independence, the small island states of the Caribbean have accepted some direct responsibility for their self-defence individually and/or cooperatively. In fairness, there are some important factors that make security self-help by the Caribbean both more necessary and more practical than is the case in the Pacific. Compactness is a key consideration in terms of cooperation and burden sharing. This illustrated by the distance between the most remote capitals within each region. The distance from Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas, to Port of Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago, is 2,311 km. However, only 750 km separates the most remote capitals of the seven member states of the RSS. By contrast, 7,835 km separates Koror, the capital of Palau, from Avarua, the capital of the Cook Islands.

Geographic compactness makes significant defence cooperation amongst the Caribbean microstates possible, while their geographic location has made some self-defence capacity more necessary. The Pacific states are remote from major global population centres, while the Caribbean states are virtually surrounded by nearby markets with hundreds of millions of potential customers. Situated around the entrance to the Caribbean Sea and close to both South America and the US, the Caribbean microstates are subject to a great concentration of significant threats to state sovereignty. Substantial amounts of commercial and private maritime traffic come close to the populated areas, requiring marine surveillance and patrolling both for border protection and for maritime safety. Despite their smaller exclusive economic zones compared with those of the Pacific microstates, their fishing resources need protection, being important to the local economies for food, export and tourism. Piracy and robbery at sea are centuries-old threats that remain very real today. Because of the proximity of the region to sources of supply as well as to the target markets, smuggling of drugs, guns and people through the region has been a significant threat to the microstates and to the destination states, particularly the US.[20] Consequently, the US Department of Defense Southern Command and the US Coast Guard have worked closely with the regional states and the RSS to provide financial assistance and equipment, as well as operational support. This is supplemented by the extra-regional states such Britain, France and the Netherlands that have some island dependencies in the region.

Pacific–Caribbean regional security lessons

The postcolonial defence infrastructure of the island microstates of the Caribbean region contrasts noticeably with that of the Pacific Islands region. PIF concerns that the Pacific regional security agenda would be pushed to the periphery of the emerging Indo-Pacific defence arrangements are well justified, because Pacific microstates do not have a seat at the table where the critical security decisions are being made. Having a substantial defence establishment with intra-regional mutual defence ties gives the Caribbean island states an important edge in promoting their security agenda with larger powers. Bilateral and multilateral military cooperation with extra-regional powers such as Canada, the UK and the US provides important avenues for defence communication. Significantly, their defence capacity also buys these states a seat in the Committee on Hemispheric Security of the Organization of American States.

If avenues for defence influence similar to those of the Caribbean island states existed in the Pacific Islands region, the PSIDS countries could more directly protect their security interests in the evolving Indo-Pacific. As it is, the mechanisms available for the PSIDS to project their defence interests are limited. The primary defence vehicle is the relatively recently formed South Pacific Defence Ministers’ Meeting (SPDMM). The SPDMM comprises ministers from Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Tonga, New Zealand, France, Chile and Australia.[21] The reach of the SPDMM demonstrates another defence contrast with the Caribbean. While the US and UK have been included as observers and Japan will be added in 2022, there is no prospect of more PSIDS representation at a ministerial level unless new PSIDS defence ministries are created. The only inclusive regional mechanism is the Pacific Islands Forum Regional Security Committee (FRSC). The FRSC serves as a clearing house for all PIF member states for a range of specialist security agency concerns, including customs, police and political security, but is not a vehicle for defence cooperation either intra-regionally or externally.

There are important domestic consequences arising from the absence of national defence infrastructures in most PSIDS. Except in Fiji and Tonga, there are no defence departments debating defence budgets in terms of national needs and priorities. Critically this absence stands as a missing element in any whole-of-government assessment regarding – as Dame Meg cautioned – the price to be paid if a country sought to commercialise strategic access for aid. Without this element, potential economic benefits cannot be balanced by cogently argued defence consequences. Similarly intra-regional priorities cannot be framed through consultations with fellow military establishments, as occurs within the RSS. The region’s ‘traditional friends’ do not have local military counterparts to sit in national departmental and government cabinet meetings where they can routinely explain and justify extra-regional strategic priorities. This lacuna can also be a serious technical concern. It goes to such issues as the protocols for sharing sensitive information. Nevertheless, the most important consequence may be at the political level, where the value of decades of Western contribution to regional defence is not fully understood and thus under-appreciated.

By contrast, the military architecture of the Caribbean microstates involves both intra-regional and extra-regional infrastructure. The cost and requirements of national and regional strategic objectives thus are far more transparent. Disputes over the balance between development needs and defence demands occur within an established framework where all interests are represented, albeit not necessarily equally. Since the Caribbean microstates directly pay for at least some of the costs of interdicting smugglers, enforcing maritime safety, fisheries protection and the like, they more readily understand how much external powers contribute to their security on a regular basis. In the Caribbean, defence burden sharing is an open and negotiable topic between the Caribbean microstates and their Western partners. This is not to argue that the Pacific microstates do not have some intuitive appreciation of the value of the Western defence contribution to their security; rather, Western defence support is expected/assumed without a clear understanding of the costs involved.

A key feature of the Western defence relationship with the Pacific region is that it is so mutually supportive that it can be taken for granted by both sides. Its near invisibility at the day-to-day level may help to explain why there are few clear examples of island states initiating an ‘adventurous’ security relationship to put aid pressure on the region’s Western sponsors. The 1976 Tongan example is probably the only one that fits the stereotypical concern. The 1985 Kiribati fisheries agreement with the USSR was not intended to be a lever for more aid but rather was driven more by Kiribati annoyance in the ongoing dispute with the US over tuna rights. Other examples of dangerous liaisons, such as selling passports, flags of convenience and money laundering, were imprudent commercial opportunism that did not challenge the strategic balance in the region. Historically it has been the analysts, media and academic commentariat who have promoted the idea that the islands will endanger Western security unless bought off by more aid. Virtually any time an apparent risk to Western security is identified, someone (and, occasionally, this author as well) will lay the blame at the doorstep of Australia or some other Western power for defaulting on an island state’s development needs.

A partial explanation for the trope of security and Western aid to the Pacific can be found in the nature of strategic challenges in previous decades. Until recently, there was no genuine extra-regional strategic pressure on the Pacific microstates. The USSR was never in a position to present a real threat to Western interests in the region. Thus, it was a relatively safe game to play the ‘Soviet card’ to convince Western treasuries to increase aid to the islands. Unfortunately the Cold War concept of strategic denial made it easy to slide this thinking into analyses that would identify strategic advantage in almost every venture the People’s Republic of China (PRC) makes into the Pacific Islands region. Initially there had been some doubt as to how seriously to apply strategic denial but this has become rather more serious since Xi Jinping ascended to the presidency of the PRC in 2013. The more aggressive approach to projecting Chinese interests globally has appeared more threatening as the PRC expands and deepens its presence in the region. Moreover, new appreciation of strategic risk in the 21st century has added to the range of types of PRC aid that have strategic implications. Communications raise significant issues for cybersecurity, hence the attempts to pre-empt the availability of this field as an area for Chinese investment in the Pacific Islands region.[22] Indeed, even aid itself has been made suspect through the propagation of the trope of ‘debt trap diplomacy’.

The China Security Agreement with Solomon Islands 2022

The controversial Solomon Islands security agreement with the PRC burst like a bombshell when it leaked on social media in March 2022. It is extraordinary on many accounts but not least for the brazenness of the PRC claim for extraterritoriality and the Solomons willingness to own the agreement. The language and content of the draft agreement suggest that it has been initiated by Beijing essentially to meet its security concerns in Solomons Islands.[23] It provides directly for the possibility of Chinese military intervention. With Honiara’s permission, the Solomons would allow the PRC to use the Chinese military ‘to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects’.[24] As a side objective, it seems clear that China wanted the same status in the Solomons through this agreement as Australia had with its 2017 security treaty. That the Solomons agreed to this while Australian and other Pacific Islands forces were in Honiara at the request of the Solomons speaks to the urgency felt by Beijing and the willingness of Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare to accommodate the PRC.

What has the security agreement gained for either party? The pluses for China could range from the strategic to the economic. A long-term strategic aim may be in part a reaction to the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS)agreement, to compel Australia to look away from the South China Sea to defend its security closer to home. A less grand political/strategic aim may be simply to establish some legitimacy as a security influence in the region. Minimally, Beijing expects the agreement to establish its parity with Australia in the Solomons and to enable it to independently protect its economic stake in the Solomons. There are some very sizeable negatives on the other side of the ledger for China. The gamble has invited higher levels of scrutiny and pushback extra-regionally as well as by regional states. The prospect that Beijing is ‘trying it on’ to validate military intervention in defence of its Belt and Road and other major projects may well serve as a negative going forward, especially if it acquires an adverse image like ‘debt trap diplomacy’.

For Solomon Islands, the negatives feel real but are vaguer than the meagre positives. Perhaps the only real benefit is the one claimed by Prime Minister Sogavare, that Solomon Islands has an additional avenue of security support.[25] Closer ties with China may produce some increased economic benefits, although these are not specified in the security agreement. Adverse consequences may include increased domestic opposition to the Sogavare government for its closer ties with the PRC. Renewed ethnic tensions or even open revolt could be expected if Chinese police or military forces were used to protect a major development project forced on a Malaita that has vowed never to allow Chinese money into the province.[26]

Thus far, there has been little to suggest that the Solomons’ dangerous liaison will serve as a catalyst for more regional states to rush into the new market for trading in strategic access. The security community sentiment appears to be holding sway elsewhere in the region. Indeed, the regional response appears to have brushed aside Sogavare’s outrage at criticism or China’s attempt to stir the colonialism pot. The President of the Federated States of Micronesia, David Panuelo, wrote immediately to Sogavare to express his concern that the agreement would put the region at risk by embroiling it directly in a broader geopolitical power struggle.[27]He argued the security community line that Sogavare has an obligation to recognise that his decision has consequences for others in the region. Similarly, New Zealand Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta reinforced this concern by asking the PIF to address how ‘the sovereign interests of Solomons may well impact on the regional sovereignty and security interests of the Pacific’.[28]

Conclusions

Whatever adjustments are made to regional security in the wash-up from China’s security agreement with Solomon Islands, there is no doubt that development assistance to the PIF states will remain a central contributor to the Australian and Western defence posture in the region. Basic humanitarian compassion for our neighbours will remain the core argument, but security-based arguments will now be advanced with greater authority to mute parliamentary criticisms or bureaucratic demands for financial savings. And for Australia, fully embracing the spirit of the Boe Declaration on climate change will remain a challenge. Consequently, critics will still attribute neglect and inadequate aid as reasons for any security setbacks in the region. Playing the ‘China card’ is unlikely to be taken out of the islands’ negotiating playbook but perhaps it will be done more cautiously. Regardless, if this card is played, the presumed threat is likely to be viewed as less hollow than during the Cold War.

One unfortunate legacy of the aid-for-security analysis of earlier decades has been the obscuring of the shared defence interests of the West and Pacific island states. The region has broadly adhered to the security community concept and its compatibility with Western self-defence needs. This assumption is being challenged overtly by the China–Solomon Islands security agreement and rather less visibly by the PRC’s relationship with other regional states. The critical challenge for both the traditional friends of the region and the Pacific island states is that the Western states have not staked out a clear approach to appropriate relations with China. Thus, there is no convincing security line for the Pacific states to take in their relationships with the PRC. The defence components of the West’s security red lines in the region often appear more like landmines that an island state must step on to learn they are there. Reactively outbidding Chinese investments in communications or other infrastructure projects to remove a defence threat only heightens the appearance of the West purchasing security through aid.

Perhaps the most difficult adjustment for Australia and other traditional Western friends of the region will be to find a way to engage in a frank discussion of the role of defence in regional security. The absence of national self-defence debates in most of the region will complicate inserting a balanced consideration of defence at the regional level. The Caribbean microstates’ solution of regionally networked national defence establishments buttressed by a security pact might have been possible once but is irreproducible today. As long as the defence contributions made by the region’s traditional friends to protect fisheries, interdict smugglers, undertake search and rescue and deliver humanitarian disaster assistance are unrecognised, they exist as uncosted aid in island national budgets. The comfortable expectation that Western security resources will be available when needed without charge or hesitation might appear as a disguised free-rider issue in the way Pacific microstates approach self-defence, but for the overall contribution the island states make through their support for the regional security community.

The China–Solomons security agreement has damaged the trust needed to maintain the regional security community concept. The cost of adjusting Western defence budgets to account for the potential risks created by the agreement will be real even if Sogavare’s pledge not to allow a Chinese naval base is upheld. These defence costs are unlikely to come out of Western aid budgets, which, indeed, can be expected to increase, if only on the logic of a half century linking aid to Western security interests in the region. It is extremely doubtful that Sogavare considered these costs in acceding to the Chinese request for the agreement, although we will never know what difference a defence minister sitting in his cabinet might have made. The problem now is persuading regional neighbours to take defence consequences more realistically in the regional security debate, especially at a time when China appears willing to make defence a regional issue.

*Dr Richard Herr is the academic director for the University of Tasmania Faculty of Law’s Parliamentary Law, Practice and Procedure course. He has held a variety of positions in the University of Tasmania since his appointment in January 1973, including Head of Department. He co-founded the Australasian Study of Parliament Group in 1979. Richard drafted the treaty establishing the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission as an autonomous agency under regional authority in 1985. He served as the consultant to draft the first national candidates’ manual for Fiji’s return to democracy in the 2014 general election.

[1] D Cave, ‘Why a Chinese security deal in the Pacific could ripple through the world’, New York Times, 20 April 2022, <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/20/world/australia/china-solomon-islands-security-pact.html>.

[2] E Corlett & D Hurst, ‘Solomon Islands prime minister says foreign criticism of China security deal “very insulting”’, The Guardian, 29 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/29/solomon-islands-prime-minister-says-foreign-criticism-of-china-security-deal-very-insulting>.

[3] ‘Hegemonic and colonist mentality behind Australia’s threats to invade Solomon Islands’, Global Times, 28 March 2022, <https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202203/1256947.shtml>.

[4] Henry Puna, ‘We will fight back, together, and win back, together’, opening remarks to the Forum Economic Officials Meeting, 6 July 2021, <https://www.forumsec.org/2021/07/06/we-will-fight-back-together-and-win-back-together-sg-puna-to-forum-economic-officials-2021/>.

[5] Dame Meg Taylor, ‘The China alternative: changing regional order in the Pacific Islands’, keynote address to the University of the South Pacific, 8 February 2019, <https://www.forumsec.org/2019/02/12/keynote-address-by-dame-meg-taylor-secretary-general-the-china-alternative-changing-regional-order-in-the-pacific-islands/>.

[6] J Blades, ‘Outgoing Pacific Forum head warns about external influences’, Radio New Zealand, 31 May 2021, <https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/443728/outgoing-pacific-forum-head-warns-about-external-influences>.

[7] JC Sharman, ‘Sovereignty at the extremes: micro-states in world politics’, Political Studies, vol. 65(3), 2017, pp. 559–575.

[8] A Greene, ‘Australian general says Chinese military presence in Solomon Islands would force ADF rethink’, ABC News, 31 March 2022, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-31/defence-general-warnings-chinese-military-solomon-islands/100954752>.

[9] Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of Solomon Islands Concerning the Basis for Deployment of Police, Armed Forces, and other Personnel to Solomon Islands, Australian Treaty Series, ATS 14 [2018].

[10] N Maclellan, The nuclear age in the Pacific Islands, The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 17(2), 2005, p. 365.

[11] Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, ‘“Biketawa” Declaration’, October 2000, <https://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/BIKETAWA-Declaration.pdf>.

[12] Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, ‘Boe Declaration on Regional Security’, September 2018, <https://www.forumsec.org/2018/09/05/boe-declaration-on-regional-security/>.

[13] Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, ‘2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent’, June 2021, <https://www.forumsec.org/2050strategy/>.

[14] KW Deutsch et al., Political community and the North Atlantic area: international organization in the light of historical experience, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1957.

[15] R Herr, ‘Regionalism, strategic denial and South Pacific security’, Journal of Pacific History, vol. 21(4), 1986, pp. 170–182.

[16] D Hourd, ‘The geopolitics of tuna: how Pacific island countries changed international standards’, Young Diplomats Society [website], 13 October 2021, <https://www.theyoungdiplomats.com/post/the-geopolitics-of-tuna-how-pacific-island-countries-changed-international-standards>.

[17] The use of PSIDS for these comparisons is mainly for the convenience of not complicating matters with the two French territories – French Polynesia and New Caledonia. Neither is in the UN. The 13 microstates amongst the Pacific Islands Forum’s island membership are Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu.

[18] Tonga’s Constitution of 1875 with Amendments through 1988, Article 22.

[19] CW Bishop, Caribbean regional security: the challenges to creating formal military relationships in the English-speaking Caribbean, Master of Military Art And Science thesis, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 2002, <https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA406428.pdf>.

[20] ‘Analysing maritime crime on Caribbean waters during the pandemic’, Marine Insight, 31 July 2020,

[21] Minister for Defence, ‘South Pacific defence ministers lay foundation for enhanced regional response’, media release, Australian Government, 8 October 2021, <https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/peter-dutton/media-releases/south-pacific-defence-ministers-lay-foundation-enhanced>.

[22] E Graham, ‘Mind the gap: views of security in the Pacific’, The Interpreter, 11 October 2018, <https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/mind-gap-views-security-pacific>.

[23] E Wasuka & S Dziedzic, ‘China’s Solomon Islands embassy requested weapons after riots broke out in Honiara, leaked documents reveal’, Pacific Beat, ABC Radio, 12 April 2022, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-04-12/chinas-solomon-islands-embassy-request-weapons/100985070>.

[24] M Shoebridge, ‘Decision to bring China’s military into the South Pacific in the hands of Solomon Islands PM’, The Strategist, 25 March 2022, <https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/decision-to-bring-chinas-military-into-the-south-pacific-in-the-hands-of-solomon-islands-pm/>.

As of writing, the signed (and presumably ratified) agreement is not is not available. All quotations on this agreement are from references to the leaked draft agreement, which said to be very close to the final document.

[25] Corlett & Hurst, ‘Solomon Islands prime minister says foreign criticism of China security deal “very insulting”.

[26] E Cavanough, ‘Solomon Islands and the switch from Taiwan to China’, The Saturday Paper, 15–21 January 2022, <https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2022/01/15/solomon-islands-and-the-switch-taiwan-china/164216520013157#hrd>.

[27] Office of the President, Federated States of Micronesia, 30 March 2022, <https://gov.fm/files/Letter_to_T_H__Prime_Minister_Manasseh_Sogavare.pdf>.

[28] T Manch, ‘Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta says Pacific leaders may need to meet as Solomon Islands prepares to ink China security deal’, Stuff, 2 April 2022, <https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/128238766/foreign-minister-nanaia-mahuta-says-pacific-leaders-may-need-to-meet-as-solomon-islands-prepares-to-ink-china-security-deal>.