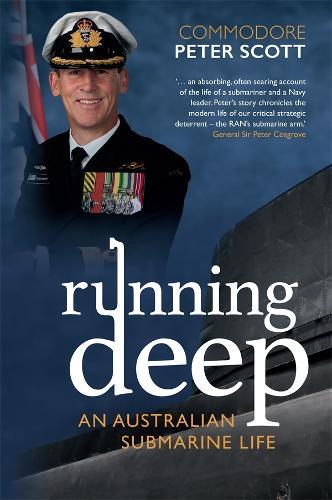

Running Deep. By Peter Scott. Fremantle Press, 2023

Reviewed by Tom Lewis

One of the most attractive aspects of this autobiography is the honesty of the author. It takes a brave man to admit both that he took his teddy bear to sea with him, and that he had problems with alcohol through much of his extensive career. Along with an extremely comprehensive coverage of a life spent in submarines this makes for a very interesting book.

Peter Scott joined the Navy in 1983 through the conventional route of the Royal Australian Naval College at Jervis Bay. Some years into his career he made the decision to volunteer for submarines, a very specialised and individual Branch. His career took him to the very top of his branch of the service. But it was not without considerable difficulties and sacrifices along the way.

There are several more aspects to Running Deep which make it a different autobiography. There are very few such submarining stories from the Australian Navy. Second, he joined the Branch when it was still running six British Oberon boats, which Australia began acquiring in the 1960s. They were excellent vessels but were eventually replaced by the Collins class. These eventually became very good submarines, but in the meantime, they had an extensive range of problems. By the time Scott was putting the final touches to this book, the nuclear program had been announced. To have insights into these three very different platforms – Oberon, Collins, and a nuclear boat – designed or destined for Australia is indeed a distinction.

Scott takes the reader through submarine training; to sea as a trainee officer and on through placements into submarines as a junior member of the command team. The book is detailed, but not in a complicated way, in its descriptions of how the boats and their various weapons systems work. It is honest too, about various problems and accidents that all submarine services have – there is plenty of accounting of other countries’ services to see that a submarining life is a difficult one. His analysis included the Kursk incident which saw a Russian submarine come to its end. There is a sense of how thinly equipped, particularly in terms of crew, the Australian service is – six boats are only just enough, and the crewing issues in such a small Branch never go away.

Scott was selected for possible command and underwent the famous “Perisher” course in Europe. It is a one-way street for anyone who passes or fails. Succeed, and you will captain a submarine. Fail, and you will not return to submarines – instead transferred out of boats forever. Scott passed and went on to eventually rise to oversee all of the submarines in the Australian fleet as their shore-based commodore.

Along the way he served in 10 different submarines and 20 different command leaderships appointments over 34 years. He also saw war service in Afghanistan and Iraq – and here’s a personal disclosure regarding the latter from this reviewer, as I was also serving there at the time, although “embedded” with the US forces.

Scott thinks the Australian public does not understand submarines. He is correct, but here is one of his statements as to their reason for being, which may help them:

In essence, we seek to see without being seen, hear without being heard and know without being known, until the day comes when we need to strike. It is precisely these characteristics, particularly their absolute lethality as a combatant, that generate the true value and potency of our submarines.

As stated, his honesty about his life in the Navy and his problems – some self-imposed; the majority imposed from without – make this more than just a mere chronological accounting. Scott does not name names in his book, preferring instead to make a comment about someone’s position and their actions he did not agree with or like. One exception is his comment about former Minister Brendan Nelson, who he says is one of those ministers who worked as a minister for Defence, rather than of Defence.

The sense of sheer hard work that comes across in the pages though, is a major concern. It would seem to be that a career like his demands the very highest level of self-sacrifice and often familial neglect, imposed by long periods of separation. How such people do it is to wonder at their dedication, and to conclude that their country owes them more than is usually understood or acknowledged. This reviewer was indeed expecting Scott to chronicle his collapse from stress, overwork, or both, but in the end, he makes it through, albeit scarred.

This would be an admirable read for anyone contemplating life in a submarining career, or for anyone who wants to understand them more – especially as Australia is in the middle of a great transition regarding this weapon of deterrence – or for anyone who likes an autobiography with a difference. Highly recommended.