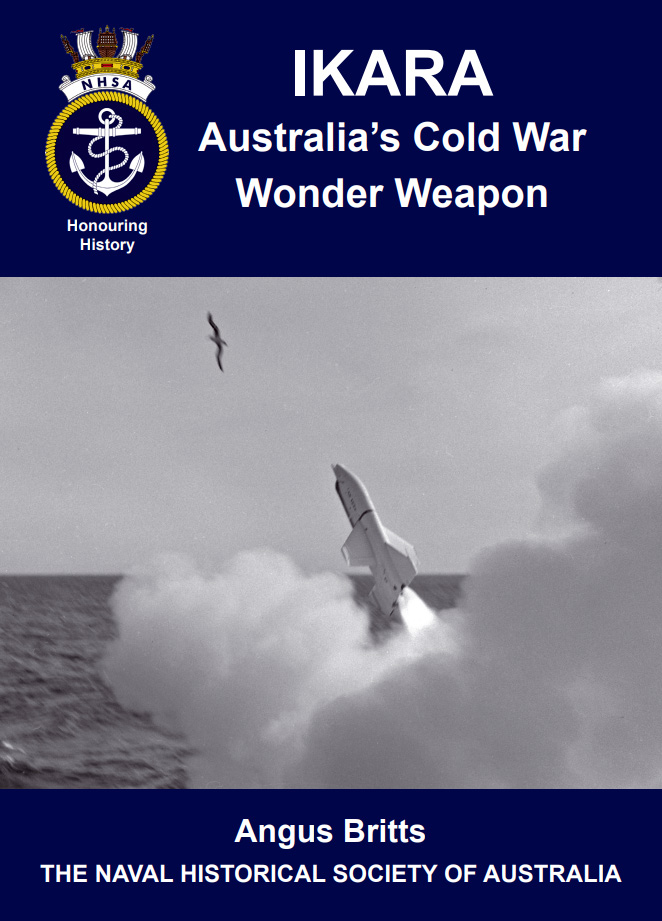

Ikara: Australia’s Cold War Wonder Weapon. By Angus Britts. Naval Historical Society of Australia, Sydney, 2021.

Reviewed by John Mortimer

In this new book the scene is set for the development of the Ikara missile via a description of anti-submarine warfare during the Second World War and the evolving Cold War situation with Russian submarine developments and available weapon and sensor systems for dealing with the problem. This is coupled with scientific research being undertaken within Australia and the UK cooperatively in the late 1940s and 1950s.

In many ways this book demonstrates how capabilities should be informed by strategic relevance and the importance of developing new capabilities from first principles, and not merely by adopting what is available and hoping that it meets our needs.

Angus Britts’ description of the senior Defence and government processes in considering the proposal for Ikara is illuminating, especially in the parochial approach of Treasury and Service Chiefs. This friction between service and civilian elements, and between the individual armed services is often levelled at the feet of the Tange Review and the establishment of the Force Development and Analysis Division. Britts through his thorough and detailed research shows that this problem was evident in the Defence system in the 1960s, and no doubt existed earlier. It is notable that the Chief of Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Sir Henry Burrell played a pivotal role in carrying the case for Ikara through the senior Defence Committees.

Development of Ikara provided ground-breaking technology in terms of its range, mid-course guidance and its ability to use externally sourced data (EXDAK). The USN’s ASROC was a fire and forget system of shorter range. Ikara’s mid-course guidance provided an ability to adjust the weapons delivery point and take account of the latest information on a target submarine’s location, thus improving the torpedoes overall effectiveness in acquiring the target.

The book clearly shows what can be achieved by bringing scientists and engineers together with naval specialists and working cooperatively to develop a proposal, to refine performance requirements and to resolve problems. It is also important to the evolution of the system once in service. This cooperation has also been the case for the mine warfare and submarine communities in the development of their capabilities, especially in the latter part of the 20th century.

The information provided on Ikara firings, both during development and when is service is extremely detailed and is a credit to Angus Britts’ depth of research. It is most unusual to find such information in any discussion of weapon effectiveness and performance.

Sales of Ikara to the UK and Brazil and other prospective customers in Europe and Japan is discussed as is the evolution of systems from Ikara, such as Turana.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book; it is an easy read and is highly recommended especially to those with an interest in Australian Defence and naval history. Scientists and those with an interest in weapons and their development will find much in this book.