Cold War Spymaster: A Legacy of Guy Liddell, Deputy Director of MI5. By Nigel West. Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2018.

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

‘Cold War Spymaster’ is part of the declassified diaries of Guy Liddell who was MI5 director of counter-espionage in World War II the service’s deputy director until 1953 when he resigned after being passed over for director.

Liddell occupied a highly sensitive position in MI5; during the war his responsibilities included overseeing agents, deception operations, political investigations and Communist counter-espionage. Although the full Liddell diaries recorded virtually every important MI5-related intelligence activity, this book concentrates on the 1945-53 period, although Nazi-buried papers relating to the Duke of Windsor, literally unearthed in Germany in late 1945, are included.

The British secret services’ post-war battle of wits against the Soviet intelligence apparatus was famously coloured by the now well-known treachery of Philby, Burgess, Maclean and Blunt. ‘Cold War Spymaster’ selects the following characters and operations:

– The Duke of Windsor’s incipient fascist associations in 1940.

– The 1945 defection of the cypher clerk Igor Gouzenko from the Soviet embassy in Ottawa.

– Nuclear scientist Klaus Fuchs’ employment by the British Ministry of Supply despite his Communist affiliations to MI5’s intense disapproval.

– The Soviet vice-consul in Istanbul, Konstantin Volkov, who offered a mother lode of information on Soviet agencies, materials and Soviet moles in the British security establishment.

– The traitorous four: Maclean, Burgess, Philby and Blunt who convulsed the British security services from the 1950s to the 1970s.

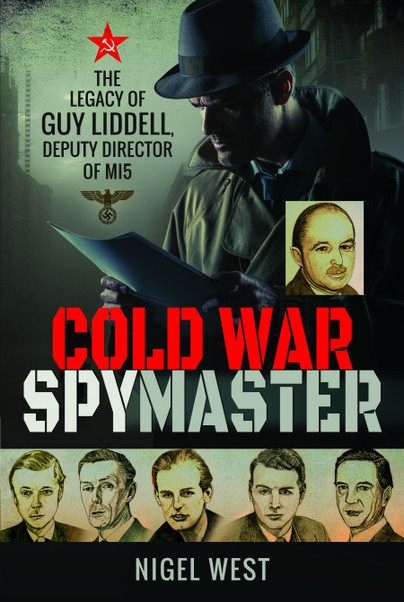

The cast of characters is very wide and requires a ‘dramatis personae’ list of who’s who in this complex tale. The text is very dense and heavy in detail; this is not a relaxing read. Illustrations are sparse; only sketched portraits of the treacherous four, Liddell himself and the Duke of Windsor. Konstatin Volkov’s list of demands, although fully outlined in the text, is reproduced as a photographic depiction in English and Russian. Appendix II: The Prime Minister’s Brief, 1978 helpfully summarises and backgrounds the activities of the treacherous four.

‘Cold War Spymaster’ is presented in a stripped and stark security service vernacular; however, this book may satisfy those fascinated by the intense early Cold War intelligence battle, which has overtones to this day. Despite the parallels this book is mainly for the specialist Cold War historian.