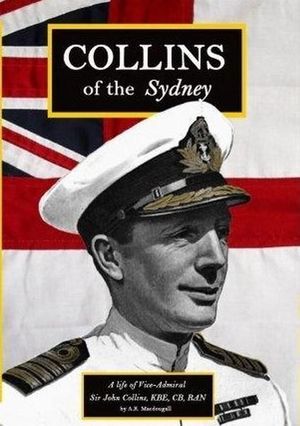

Collins of the Sydney: A Life of Vice-Admiral Sir John Collins. By Anthony K. MacDougall. Clarion Editions, Mudgee, 2018.

Reviewed by Ian Pfennigwerth

TONY MACDOUGALL has taken on the necessary but difficult task of researching and writing a biography of the first Australian officer to command the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Vice Admiral John Augustine Collins KBE, CB. The necessity springs from the central role Collins played in the development of RAN capabilities in operational, organisational and international fields. He is probably best known to Australians today because of the class of submarine named after him.

However, between his acceptance into the RAN College as a member of its first entry in 1913 through to his retirement in 1955, John Collins was associated with almost every stage of the RAN’s progress from a small element of the mighty Imperial Royal Navy to an independent and regionally significant maritime force in its own right. The difficulties arise because the RAN has been far from assiduous in preserving its own records and because John Collins was a notably private person, creating and leaving nothing substantial as a documentary trail of his life, its events and his reflections on them. So, the first plus for this book is that it was written at all.

The author has deployed his considerable skills to explore a wide range of material and anecdotal sources in his efforts to present the whole of Collins’ life, including his family’s history and the interactions of his mother and older siblings with John, the youngest. Collins’ selection for the RAN College in 1913, his experiences and achievements there and his subsequent service with the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet in 1918 are recorded. Clearly a ‘comer’, John Collins absorbed well the lessons learned from his operational experience and specialist Gunnery courses to become a highly-regarded Gunnery expert. His career thereafter led though several operational postings and service in the British Admiralty to command of the light cruiser HMAS SYDNEY in 1939. As the book’s title suggests, his name was forever linked with that ships because of her exploits in the Mediterranean in 1940 under his command, notably the sinking of the larger Italian cruiser BARTOLOMEO COLLEONI.

Great though these achievements were, less prominence has been given to Collins’ pivotal role in Singapore in 1941-42 in first planning for the eventuality of a Japanese attack on British, Dutch and US colonial possessions in Southeast Asia and then in saving as much as possible from the wreckage of the Allies’ failure to honour their commitments to the plan. Many of the vessels and survivors who reached the safety of Australia after the fall of Singapore in February 1942 owed their lives to the quiet but effective measures taken by John Collins. Personally, he remained mindful of those he was not able to save, including the men of PERTH and YARRA lost to superior Japanese forces.

The author carefully charts Collins’ path from his posting to Western Australia after his return from Java, via command of the heavy cruiser SHROPSHIRE and active service in the South West Pacific Area, to his posting in command the Australian Squadron in June 1944. Severely wounded by the kamikaze attack on his flagship AUSTRALIA in October 1944 at Leyte Gulf, he returned to his command after convalescence to lead the Squadron into Tokyo Bay for the Japanese surrender in September 1945.Maccougall notes that Collins’ later progression to become the first Australian officer to command the RAN was, in significant part, through the reputation he had gained in senior political circles for his ability to meet any challenge placed before him, which counted more in his favour when the decision became necessary than his alleged lack of senior command experience.

Throughout John Collins’ tenure as Chief of Naval Staff from 1948, which was extended twice to 1955, he built upon the foundations laid by his predecessors to set the RAN on a course towards strategic independence and development of a force structure suited to Australian circumstances. Although thoroughly steeped in the British way of doing things, he had enjoyed and appreciated his wartime exposure to the US Navy and saw clearly that the post-war development of Pacific cooperation was more important than retaining traditional ties with the Royal Navy. This phase of his career clearly caused the author some anguish. It would be fascinating to learn how Collins argued his case and influenced his colleagues and political masters towards adoption of his views but the surviving records simply do not provide this information. Famously reticent about his service and personal life, Collins left us to speculate on this.

What to do with a youthful former Chief of Naval Staff? Offered the ambassador’s post in Manila, Collins declined because his wife Phyllis was recovering from serious injuries suffered in a domestic accident, but he was happy to be appointed as High Commissioner to New Zealand. There he served effortlessly and effectively before retirement in 1963.

Tony MacDougall presents John Collins as a modest man who knew his own worth and applied his considerable capabilities to good effect throughout a glittering career, in and out of the RAN, in more than 50 years of service to Australia. But he remains somewhat of an enigma, and his determination that nobody, not even his journalist and author brother Reg, should ‘make a fuss’ about him and his exploits means that Tony’s task presented enormous difficulties. He has made a very competent job of it, nonetheless.

The book is easy to read and should appeal to all readers interested in learning more of this important figure in Australia’s national and naval history.