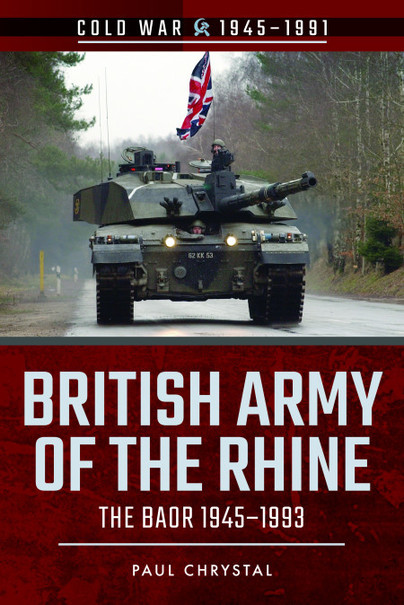

British Army of the Rhine: The BAOR, 1945-1993. By Paul Chrystal. Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2018.

Review by John Johnston

THIS book, one of a series of Pen and Sword monographs on the Cold War, recounts the story of the British Army of the Rhine, the 55,000 troops and the tactical air force which the UK kept in Germany between the end of the Second World War and the end of the Cold War. Originally an army of occupation, the Rhine Army evolved into one of the pillars of NATO’s deterrence strategy and symbolised the British commitment to European defence and to a sovereign Germany.

But, with roughly two-thirds of the British Army and the Royal Air Force on its strength and with an inventory of complex and hugely expensive armoured vehicles, the cost of the Rhine Army was prodigious. By the 1980s, it was absorbing almost half of the UK defence budget. Right-wing commentators revived demands that had been made repeatedly since the 1950s for the troops to be withdrawn or for the Germans to pay all the costs of stationing them in their country, blithely ignoring that the divisions this would have been created in the Western alliance were long-held objectives of Soviet agitation and propaganda.

Secondly, once it had been decided to station troops permanently in Germany, provision had to be made for accompanying families. Cantonments were hastily erected on the outskirts of towns throughout Lower Saxony and North Rhine Westphalia. Some of the cantonments were modelled on English garden suburbs and others were rows of houses and flats built on whatever vacant land was available, but each gave troops and their families housing, schools, medical facilities, and shops and supermarkets, as well as social, recreational, and welfare amenities.

Given language barriers and locations, the cantonments were self-contained communities and living isolated in a foreign country and separated from friends and relatives created social and psychological problems, which fears of what would happen if there should be a Warsaw Pact attack aggravated. Those problems were further aggravated in the 1970s and 1980s when up to a division’s worth of troops from the Rhine Army deployed each year on counter-insurgency operations in Northern Ireland and when the Provisional Irish Republican Army retaliated with terrorist attacks on British families and installations in Germany. Providing an English language radio station and later relaying selections of English television programmes may have alleviated some of these problems but it could not eliminate them.

The Rhine Army ought to be a topic of interest to historians, political scientists, and sociologists, who will find Paul Chrystal has provided an invaluable guide for their journeys. He outlines the strategic environment within which the Rhine Army operated and describes the alterations and adaptations that were made to the army’s organisation, equipment, and tactics as that environment changed. Case studies examine issues such as post-war reconstruction and denazification as well as relations between the British military and German communities, while the final chapter of the book describes the social infrastructure and facilities which gave service families a sense of community and well-being.

The book is copiously illustrated, with many of the photographs being from the collection of his brother, David Chrystal, who served in the Royal Signals towards the end of BAOR and there is an exhaustive list of sources from The National Archives to books and articles, sometimes in obscure academic journals, to Internet websites. Paul Chrystal set himself the task of correcting the omission of ‘the hugely expensive, long-term stationing of troops in West Germany’ from accounts of the British contribution to Western defence during the Cold War and to tell the story of ‘the lives of the thousands of servicemen and their families [who were] living on the front line in Germany’: in that he has succeeded and set out the markers for others to follow.