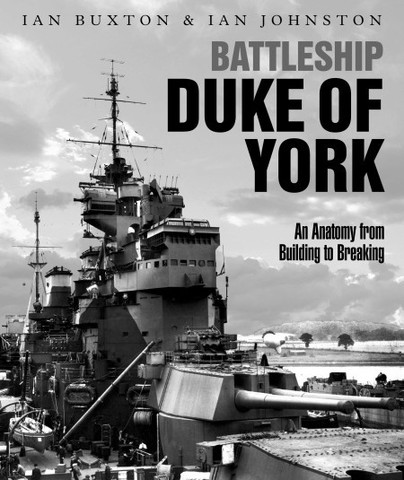

Battleship Duke of York. An Anatomy from Building to Breaking. By Ian Buxton & Ian Johnston. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, Yorkshire, 2021. ISBN 978-1-5267-7729-4

Reviewed by David Hobbs

This carefully prepared book describes how HMS Duke of York was built in the Clydebank shipyard of John Brown and Co and how she was broken up at Faslane after only a decade in operational use and seven years in extended reserve.

It is an outstanding description of how Duke of York, the third of the five ships of the King George V class to be completed, was designed, procured, constructed and ultimately dismantled. It is not, and nor was it intended to be, an operational history. Many earlier books have been described as anatomies of specific ships but this example, written by two authors who are the leading specialists within this genre is, in my opinion, the best example to date. The text is derived from a wealth of primary sources examined during protracted research and the authors benefitted from the fact that unlike other shipbuilders John Brown’s yard employed its own professional photographers. They exposed over 600 images during Duke of York’s construction which were preserved within the National Records of Scotland after the yard closed. Most were glass plate negatives and their survival was, in itself, remarkable. More than 150 of these were used to illustrate this book; the majority are of exceptional clarity allowing the authors to explain what is happening and what the men visible in shot are doing down to the finest of details. Changes in shipbuilding methods over the past century are highlighted by the fact that some of the ‘rule of thumb’ techniques being used by the men in these photographs are now forgotten despite being common practice just within living memory. This book is, therefore, not just a detailed description of one ship’s construction, it also describes methods and skills that no longer exist. Duke of York was one of the last great examples of British battleship design with an armoured hull created out of frames and riveted plates. Machinery and the enormous mass of the gun turrets and their rotating structures were installed after launch. I had not realised the extent to which a hull being launched had to be strengthened with timber beams within its large empty spaces to withstand the stresses it encountered as it entered the water in an incomplete state. The purpose and design of poppets, wooden structures that spread the load of the fine forward and after extremities of the hull as it moved down the slipway, are also described and explained in diagram form.

Clear diagrams support the text and more than 50 are included to show the shipyard layout and how specific elements of the design functioned. Some are drawn in colour to illustrate the Mark II twin and Mark III quadruple 14-inch gun turrets and their rotating structures in both plan and elevation. These work perfectly with their captions to explain how they operated. So too do the coloured diagrams of how the magazines, shell rooms and secondary 5.25-inch turrets operated. The drawings of the gun breeches, shell room arrangements and the methods used for embarking and stowing ammunition are particularly informative. The book also contains coloured reproductions of the ship’s ‘as-fitted’ drawings in side elevation, cross-sections and plans for every deck. The originals were prepared by the shipbuilder as part of the building contract for use in the Admiralty’s Construction Department and now form part of the National Maritime Museum’s invaluable collection in the former Brass Foundry at Woolwich. The side elevation opens out into a gate-fold which covers the four pages from 203 to 206. Printing is of high quality so that a magnifying glass can be used to study fine detail and read the writing on the plans. Readers can, therefore, become sufficiently immersed to ‘find their way around the ship’ as I did. The originals are a beautiful example of the draughtsman’s art and these reproductions pay them the respect they deserve.

In addition to their description of the ship itself, the authors describe the work force that built her and the book is dedicated to their memory. Of interest, she was built on the same slipway as both HMAS Australia I and HMAS Australia II and so many of the skills and techniques described so carefully in this book would have applied equally to them. Some of the men who worked on the latter may well have worked on Duke of York a decade later. About 10,300 men were employed in the yard in December 1939. These included draughtsmen, loftsmen, shipwrights, riggers, anglesmiths, shipsmiths, platers, drillers, riveters, caulkers, welders, pattern makers, fitters, plumbers, electricians, joiners, sheet iron workers, painters and men employed by sub contractors such as Vickers Armstrong and Harland and Wolff who made the gun mountings. Their tasks are described in fascinating detail, together with graphs to illustrate the numbers working on Duke of York at any one time and even what they were paid.

The authors note with regret that although British shipyards built more battleships than any other nation and the Royal Navy contributed more than any other to the development and deployment of this type of warship, no battleship has been preserved in the UK. Had it proved possible to do so, Duke of York‘s short but significant career would have made her a strong candidate. She was Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser’s flagship on 26 December 1943 when, as part of the task force covering a Russian convoy, she sank the German battlecruiser Scharnhorst in the Battle of the North Cape. When Admiral Fraser moved from the Home Fleet to create and command the British Pacific Fleet, BPF, he retained her as his flagship and she was a familiar sight alongside Garden Island Dockyard during 1945. She was in Tokyo Bay for the Japanese surrender which was actually signed on an oak table lent from her Admiral’s accommodation to the USS Missouri for the occasion, replacing an austere American steel table which was deemed less suitable by Admiral Fraser. Maintenance was carried out in the Captain Cook dock in July 1945 and she finally left Sydney in December 1945. A small piece of Duke of York can still be seen in Sydney, however, in a memorial to the BPF, comprising a treadplate with the ship’s name from her quarterdeck and a badge which were both removed when she was scrapped in 1958. They were placed near the site of the BPF’s former headquarters, together with an explanatory plaque, on the initiative of the Naval Historical Society of Australia and unveiled by Rear Admiral G D Moore CBE in 1973. The memorial has subsequently been moved to its present site inside the RAN Fleet Headquarters a few yards away.

In the absence of a preserved British battleship, this book takes readers as close as they can get to understanding how HMS Duke of York was built and how her armament was constructed and operated but it offers much more than that, it pays a fitting tribute to the men who built her and the skills they used to do so. It is, therefore, an important means of preserving an understanding of the work force at Clydebank as much as the ship itself. It deserves a place on the bookshelf of anyone interested in the history of warships, shipbuilding or even heavy engineering techniques that have faded into history. In my opinion it is one of the best books to emerge within the naval genre during 2021 and I wholeheartedly recommend it to a wide readership.