Battle in the Baltic. The Royal Navy and the Fight to save Estonia & Latvia 1918-1920. By Steve R Dunn. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, 2020. ISBN 978 1 5267 4273 5.

Reviewed by David Hobbs

Steve Dunn has written a series of successful books about naval operations in World War One for Seaforth Publishing and this book follows them logically by covering RN operations in the Baltic from the Armistice that ended the fighting on the Western Front in November 1918 to the end of 1920.

It describes operations which have largely been forgotten but which have considerable resonance with contemporary peace-keeping operations by the Commonwealth navies. While 11 November 1918 marked the end of hostilities for the majority, a significant force of British cruisers and destroyers was immediately deployed to the Baltic as part of an effort to contain Bolshevik expansion. Whilst the British Government was prepared to commit ships, however, it refused to commit ground forces to Estonia and Latvia. Forward bases for RN ships were established in Denmark and Finland and Rear Admiral Walter Cowan soon found his ships in action against Bolshevik warships in the Gulf of Finland and bombarding the Red Army ashore in defence of the independent Baltic states. German Army divisions still dominated large areas of land under generals who acted as war lords, untouched by the Armistice.

As the situation ashore deteriorated, the RN found itself having to use force against a variety of hostile groups. These included the Red Army and Navy led by Leon Trotsky; considerable formations of German troops, known as the Freikorps, who intended to keep the Baltic states under German domination and White Russian forces under warlords who wanted to rebuild a Russian Empire which included the Baltic states. War-weary and desperate to reduce expenditure, the British Government was torn between attempting to curb the advance of Bolshevik forces and support the Baltic states on the one hand and the desire to withdraw altogether on the other. Britain’s ally France provided a small flotilla of warships, but the USA stood aloof from formal alliance, referring to itself as an ‘associated power’, although it did provide humanitarian aid at times. The result was a limited war which in some ways foreshadowed the Western involvement in recent conflicts in Iraq, Libya and Afghanistan. Sailors, often ill-equipped for harsh winter conditions were sent into harm’s way under political constraints that often limited their ability to take the most appropriate action in circumstances that could change rapidly. Political indifference and a failure to explain to the men and their families precisely why the RN continued to be deployed in what was widely considered to be somebody else’s war led in some cases to mutinies which the author describes in detail. That indiscipline should disfigure the RN’s normal tradition of discipline under active service conditions is a measure of the difficult circumstances under which this campaign was carried out.

Since the British Government never accurately described the mission it expected Admiral Cowan’s force to carry out, it is not easy to ascribe success or failure to it. It is certainly true, however, that RN command of the Baltic and intervention with gunfire in support of Estonian and Latvian volunteers against the Red Army, Freikorps and White Russians enabled the states to maintain their independent status. To this day the RN role in Latvia and Estonia is commemorated in annual ceremonies and there are memorials to the men who died. On the other hand, the Bolshevik forces were not prevented from seizing absolute control in Russia and were to remain a threat.

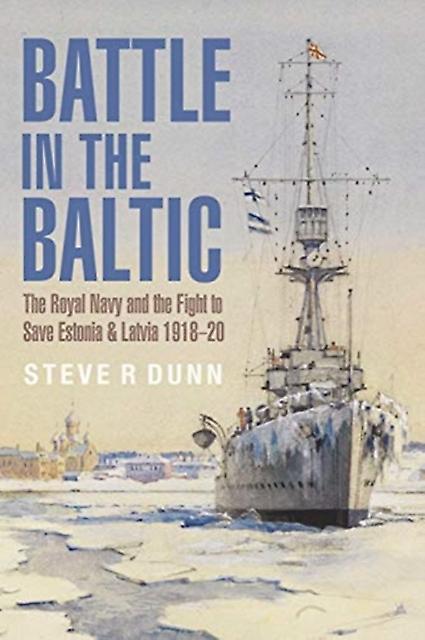

The scale of operations can be deduced from the fact that 128 sailors died and 3 Victoria Crosses were awarded; one of the latter to Lieutenant A W S Agar RN who torpedoed and sank the Red armoured cruiser Oleg in Kronstadt with a single torpedo from CMB-4. The British War Medal continued to be awarded to those who served in the Baltic for two years after the Armistice that had supposedly ended hostilities. The book’s cover illustration is a painting of the cruiser Caledon ice bound in Libau harbour, Latvia, in February 1919; it gives the reader a good impression of what conditions must have been like in winter.Overall, this is a well-written and very readable account of an important but little-known campaign that still has relevance today. It is interesting to reflect on just how many lessons about the application of force in limited war situations have been learnt and then forgotten. The author reminds us that intervention can lack value if the aim is not well defined or if forces are withdrawn before the aim has been achieved. Apart from its obvious interest to readers with an interest in naval history, this is a book that any naval professional or, dare I say, politician involved in foreign affairs should add to their reading list. I recommend it highly.