Attack on Sydney Harbour – June 1942. By Dr Tom Lewis OAM. Published by Big Sky Publishing. PO Box 303 Newport, NSW 2106. ISBN 9781922765383

Reviewed by Desmond Woods

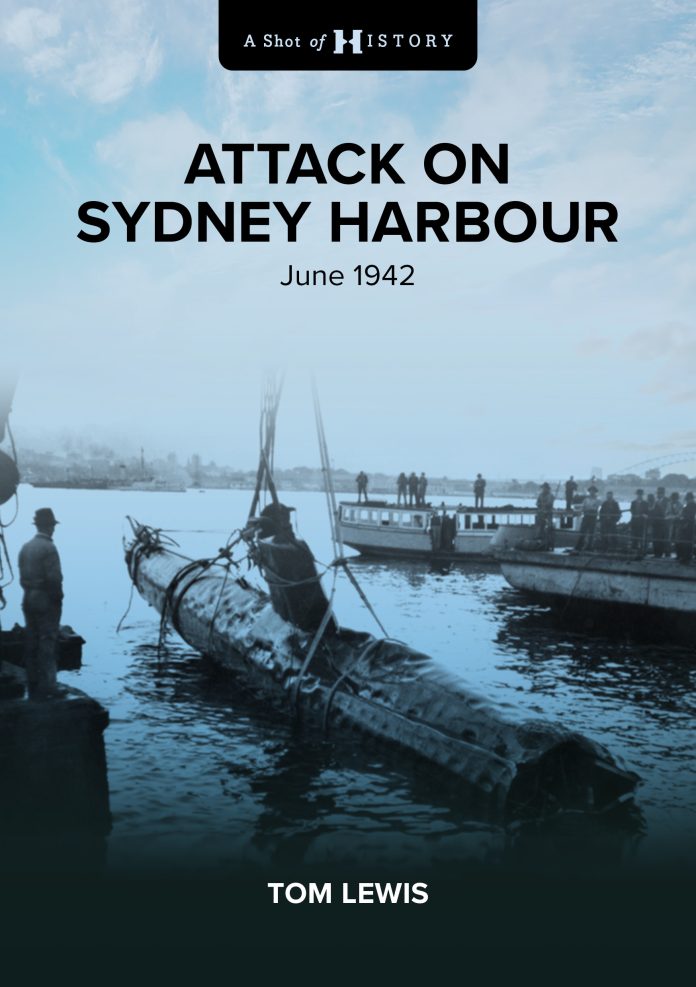

The principal facts behind the Japanese midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour in June 1942 have been understood, and the actions and movements of every vessel on both sides have been plotted, for many decades. The twenty-one Australian and British naval ratings who died in the torpedoed wooden ferry Kuttabul, moored alongside at Garden Island, were buried with naval honours. The ashes of the cremated Imperial Japanese Navy submariners were returned to their families in Japan later in 1942. What then can be the purpose of a new book eighty years on from these tragic events?

My thinking before I opened the book was quickly changed by the realisation that this account of the attack covers a far wider field than just the events of a lethal June night in Sydney Harbour in 1942. The author takes the reader back to the previous decade to understand the motivation of the navies involved on both sides, the secret evolution of the midget submarine, and the assumptions about its practicality as an operation of war. The book reveals that in the weeks leading up to the operation both sides believed that they would be in control of the defences of the channels leading into the harbour itself. The Japanese believed they could bypass them and the defenders believed they would hold. The night of the attack proved that they were both right and wrong. The bravery shown on both sides by junior officers and their sailors revealed that their senior officers’ plans for attack and defence were overly optimistic.

In planning the Sydney attack the Japanese Naval High Command may have been working off an assumption that their midget submarines had caused havoc to the USN battlefleet at Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Because they were all sunk it was not appreciated till after the war that none of the midgets had got remotely within torpedo range of Battleship Row. The Japanese model of a successful attack on an allied harbour by midgets from mother subs was therefore considered bold, but not unreasonable – provided the safe return of all the midgets to their mother submarines was not regarded as mission critical. Short battery life and likely enemy action after a successful strike on a major allied warship were equally likely to doom the two-man crews of the Midgets. But this was not a suicide mission, anymore than the Royal Navy’s X Craft attacks on Tirpitz. A theoretically practical means of recovering crews and their boats after both raids was planned.

The midget’s target for the night was the heavy cruiser USS Chicago which had been spotted from the air by an IJN submarine launched sea plane. Photo analysis mistook Chicago for the battleship HMS Warspite, which had been in Australian waters in early 1942. All efforts were directed at turning this large and valuable target into a scene of carnage right next to Fort Denison.

The only midget commander to get into position to attack Chicago was Sub Lieutenant Ban in M24. His two torpedoes passed very close. One may even have gone under the ship’s hull. It was set to run one metre too deep to strike Chicago – perhaps aimed at the deeper draft of Warspite. However it is clear from the attack that Japanese optimism that such a blow could be successfully made was not unfounded. It was Ban’s inexperience in lining up his shot and luck which may have saved up to 690 American lives of the heavy cruiser’s ship’s company.

On the Australian side, the seaborne raid at Darwin and the loss of life there had been largely obscured by the censors. The southern states and the chances of a carrier borne air raid on a southern city was rightly thought to be unlikely. But preparation to repel bombardment of the city by surface forces was well in hand. The coastal heights at Sydney’s entrance, and north and south of it, bristled with manned heavy artillery emplacements. The defences of the point of entry, the surface and sub surface of the harbour were inexplicably incomplete. In retrospect that was the most important and most neglected vulnerability.

The Royal Navy senior officer and in Sydney, Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould DSC RN, was in theory the ideal officer to command the defence of a naval anchorage or harbour. He had recently overseen the building of the anti-submarine defences at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands to ensure that the tragedy of the torpedoing of the battleship HMS Royal Oak could never occur there again. But he inherited on arrival in his command a half-completed boom defence and, as the book points out, the lack of urgency in getting it finished appears to have been culpable negligence for which the blame extends well beyond Muirhead-Gould to the local and national authorities. Complacency and general lack of understanding of new Japanese submarine capabilities were rife and this negligence cost lives.

One chapter of this well researched book deals with the lack of recognition for the efforts of the crews of three small naval vessels that intervened with depth charges and successfully countered the efforts of three of the four midget boats to get into the harbour. This may not have been oversight. The Australian wartime Government and its Naval Board were not in the business of drawing attention during early 1942 to the tragedies and near misses being inflicted on the RAN and its allies at sea. These costly disasters starting in November 1941 included the loss of HMA cruisers Sydney and Perth and the sloop Yarra. These lost battles were defeats as well as tragedies. An unanticipated attack in June on Sydney itself and twenty one dead was not a cause for anything but grief and anxiety. Perhaps this helps explain the underwhelming response of the Australian Naval Board to Muirhead-Gould’s recommendations that it should give due recognition to the bravery and effectiveness demonstrated by navy crews defending Sydney Harbour. Congratulations were sent by signal and notations in officers’ records were made, but no medals were issued to anyone. The author believes that this error could still be addressed.

This new book is a comprehensive account of the attack and what preceded and followed it. It covers in forensic detail the men, the vessels, the successes and failures on both sides. It brings together from many sources information only to be found in out of print books and hard to access records. Tom Lewis has shone a necessary light on the darker corners of this unique episode in Australia’s naval history and reminds the reader that underestimating what a determined enemy can do in wartime is fraught with danger. Above all, the message of the book is that relying on the distance of our Australian cities from an enemy’s centre of gravity did not work in 1942 and certainly will not work if the challenge comes again this century.

I highly recommend this book to the general reader and to the naval enthusiast alike. I hope it will be read by those who are charged with defence of our container depots, naval bases, fuel depots and maritime communication and underwater cables. Tom Lewis has reminded us of the perils of lack of preparation in peacetime and the price to be paid in war for not recognising new technologies and methods for striking at Australians from the sea.