Prior to this year’s commissioning of the offshore patrol vessel HMAS Arafura, the RAN had an earlier attempt at such a vessel. It was the Offshore Patrol Combatant (OPC) in the late 1990s. This article published in the November/December 1996 edition of Journal of the Australian Naval Institute by ‘Argos’ provides an overview of the ultimately ill-fated project.

The OPC Project

The OPC project is almost unique in Australian naval history. Not since the abortive Light Destroyer (DDL) in the 1970s has the RAN had a project for a warship which is to be both designed and built in Australia. While purists may not call the OPCs major warships, they will probably be the most significant capital acquisition the RAN makes in the next decade.

The OPCs will be the latest RAN patrol force, following the Fremantle class patrol boats (FCPBs), the Attack class and during World War II the Bathurst class corvettes/ minesweepers. Though they are intended to replace the FCPBs they do not sit very well in this company. None of the Bathurst class, A boats or FCPBs had or have such significant warfighting capabilities as the OPC will have. During World War II the Bathurst class had little or no capability against any serious form of determined attack; they provided escort against submarines and armed motor boats, transported troops and supplies, conducted minesweeping operations, and conducted the myriad other minor operations that engage a navy during conflict. That their losses were not greater was due to being employed in low threat areas and because they were involved in tasks which, despite their importance, did not usually justify significant effort by enemy forces. (This should not be taken to mean that the corvettes during World War II were never in danger, merely that the threats to them came from a different league to those which faced, for example, the USN carrier task groups.)

The OPCs are capable of all that their predecessors were in (mine clearance operations excepted) and more. The designs thus far seem to be very well considered, the project has taken cognisance of the potential in automation, mission specific manning and presumably weapons/sensor fits, improved maintenance cycles and hence availability, and much much much more. Lessons learnt from the project management and design of the Collins and Anzacs have been assimilated. It does seem to be in many respects a model operation. But there are many questions unanswered, And like the project itself, which is already late in terms of replacing the FCPBs, these questions should have been answered before now. That being the case, there is no time like the present.

The OPCs are intended to be based in Darwin, along with the new hydrographic survey ships. Though no one has mentioned it so far, this seems suspiciously like ‘three ocean basing”. And there are lots of good reasons for the RAN to have a significant presence in Darwin. There are many questions which the Navy must think through first. Does Darwin have sufficient infrastructure to support massive increases in both the Navy and Army presence there? What are the costs in terms of operating more and larger ships from there? Everything must come by road or by sea. What are the strategic implications of this? What are the personnel costs? In many respects these personnel issues are the biggest of all. They are certainly the ones which will attract the most attention from the naval community, and they are the ones which are perceived to have received the least attention during the process of implementing the ‘two ocean basing’ policy. A final and reasonably valid question is whether the RAN is big enough to support three major bases. None of these questions seem to have been addressed, yet their impact on the OPC project, and through it the RAN, is substantial.

Another question which has been addressed to a small degree is how the OPCs will operate in peacetime. The RAN has substantial constabulary tasks related to the protection and enforcement of Australia’s sovereign rights in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The OPCs will have a medium calibre gun, a naval combat data system, a helicopter, a surface to air missile system, and the accompanying communications, fire control and sensor systems. The crew who operate these will presumably need consistent continuation training in the procedure and tactics needed to operate them. How compatible will this military training requirement be with the constabulary tasks? Will there be a need to constantly visit the EAXA or will the requisite support be provided in the NAXA as well? And how will these constabulary tasks be conducted in a time of conflict, for they will not cease just because a war is imminent?

The RAN’s commitment to constabulary tasks, which currently garner the bulk of the FCPB fleet’s seatime is measured in sea days. Modelling of its performance suggests that the OPC will be many times more effective than a Fremantle. But this increased effectiveness cannot be measured in sea days. What measure can the RAN provide to demonstrate the improvement of its commitment to constabulary tasks. Such a measure must be accepted by at least a majority of the various Government departments which have a stake in managing, monitoring and exploring Australia’s EEZ. This in itself is a major undertaking and open to political and bureaucratic friction, in the same way that the OPC’s constabulary tasking will be subject to operation friction. (Friction is used in both cases in the sense that Clausewitz expressed).

If the RAN cannot fulfil its peacetime constabulary functions, this will lead to pressure for a coastguard which will. The RAN is already a small service and formation of a coastguard would certainly mean reduced funding and increased competition for scarce personnel and other resources. If there is a critical mass for the RAN, the RAN is probably at or near it and reductions below its current size would mean a greater than proportional loss in capabilities. In this sense the OPC project is very high risk for ihe RAN.

Another question worthy of consideration is what the RAN is going to do in the interim between the delivery of the OPCs and the end of life for the Fremantles. Even if 10-12 OPCs are built the last may not be in service till around 2010, by which time, presumably, all the FCPBs will have been retired.

The rationale for the OPC is based around the current axiom that peacetime requirements are not to be force structure determinants, the corollary of which is that all ADF assets must have a primarily military function. That this should be the main tenant of ADF planning is neither surprising nor contentious. However, the guiding rule for interpreting the old Queen’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions is worth hearing in mind: the letter killeth, but the Spirit giveth life. Navies have significant peacetime responsibilities; constabulary and diplomatic functions which are in many cases unique to naval forces and are in addition and complementary to their military functions. In an era when these constabulary and diplomatic functions are taking on more importance, perhaps it would be wise for the RAN and the ADF to consider including them as force structure determinants. They would not have to be principal determinants, but to exclude them makes any study of force structure unnecessarily artificial; monocausal solutions are rarely satisfactory.

The significance of the OPC project to Australia’s warship building industry is also considerable. The OPC will fill the gap between the delivery of the last Anzac and the commencement of the first FFG replacement. If the OPC project is not successful then what are the implications for the major warship building industry which has been developed over the last decade? Are the FFG and Anzac upgrades sufficient to maintain the infrastructure, despite operation at reduced capacity, until another major project commences? Is this a force structure determinant?

The OPC project is very important for the RAN, Transfield and Australia. Consideration of the domestic implications, some of which have been set out above, is complicated enough. But there has been little consideration of these issues, perhaps because of concern over implications for the potential partnership with Malaysia to build a Joint Patrol Vessel (the OPV in a multi-national guise). The rationale being that Transfield’s bid may be weakened if there is any perceived Australian vacillation over the project.

This reasoning is probably spurious. If the Malaysians were seriously concerned about Australia’s commitment to the project, suppression of Australian discussion would most likely increase rather than allay their fears. Nor would it prevent the Malaysian Government from quickly working out in broad terms what the Australian concerns were. Surely our experience with and promotion of confidence building measures would suggest that some degree of transparency was desirable.

Even if Malaysia does not choose the Translield bid and give life to the JPV, the RAN will still have a requirement to replace the FCPBs. The starting point for that process will surely be the OPC or some derivative of it. Thus Australia’s commitment to an OPC must be quite firm. It is how we implement the OPC, and the implications it has, that need consideration, not whether we need one. The OPC has great potential for the RAN, the ADF and Australia. It would be a great shame and a big setback if it went the way of the DDL. The RAN must take a broad view of the OPC project. Excellence within the project is not enough.

Postscript

The OPC did indeed go the way of the DDL. The concept behind the OPC originated in the 1991 Force Structure Review and it was to bring forward the FCPB replacement, acquire a much larger hull form to cope with a broader range of sea states, better endurance, etc., and build the relationship with Malaysia. The Seasprite helicopter was selected to be able to operate off both the OPC and the Anzacs.

Malaysia’s OPV project decision to contract Germany’s Blohm & Voss and not Transfield was the immediate cause of the OPV cancellation, but the diplomatic relationship with Malaysia (Prime Minister Keating calling Prime Minister Mahathir recalcitrant) and Finance/Treasury scepticism were also potentially significant.

In regard to the Australian decision, anecdotally there was scuttlebutt that the RAN had cold feet about ‘going it alone’ on an OPV, and funds were better spent on Mine Hunter Coastal build instead. The FCPBs were extended in service for another 10+ years until the Armidale class was contracted.

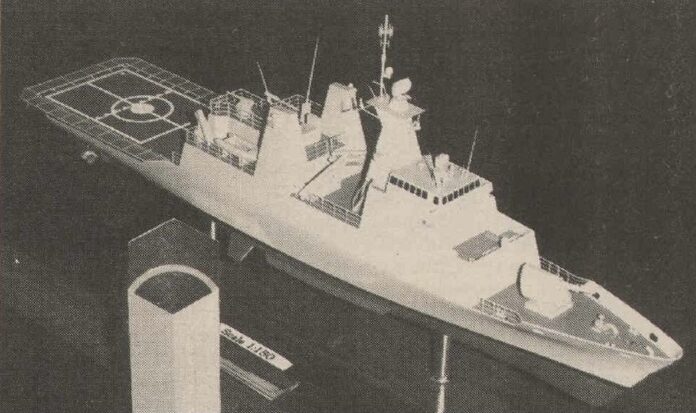

The OPC was to be 75 metres in length with a displacement of ~ 1250 tonnes. The ship would have a range of 6,000nm @ 12 knots with a maximum speed of >25 knots. Her complement was to be about 75. She would be fitted with a medium calibre gun, a close range gun and an intermediate sized helicopter. She would be fitted for but not with an anti-ship and surface-to-air missiles.