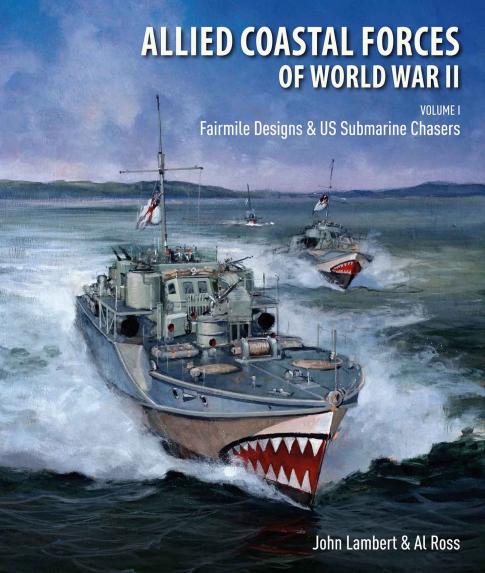

Allied Coastal Forces of World War II: Volume 1, Fairmile Designs and US Submarine Chasers.By John Lambert and Al Ross. Seaforth, Barnsley, 2018

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

THIS encyclopaedic work examines Fairmile Motor Launch (ML) designs, Harbour Defence Motor Launches (HDML) and the US Submarine Chaser (SC) 497, their weapons, sensors and equipment. Every ML is listed, together with its in-service dates and production statistics by boatyard. The book was first published in 1990 with Seaforth Publishing making it available again in 2018.

Mass produced wooden minor warships first appeared in World War I. The Royal Navy sought large numbers of anti-submarine craft to counter the U-boat threat in coastal waters. The Admiralty ordered 500 boats from the US Elco Launch Company, specifications of which included a speed of 19 knots, length 80 feet, displacement 42 tones with an endurance of 2100 nm at 11 knots. They were fitted with primitive anti-submarine weapons as the depth charge had not been developed at that time. They were judged to be too small in service – a 100-120 feet length was more suitable; however, the war ended before any new designs were implemented.

Serving in the RN Dover patrol was a Lieutenant Noel Macklin RNVR. This wealthy young adventurer developed his interests in yachting, flying, car-racing, and innovative business pursuits in the interwar period. With war looming in the late 1930s he conceived a design for a new generation of mass-produced wooden coastal MLs to be assembled in kit form by private boatyards, freeing specialist builders such as Vosper, White and British Power Boats to concentrate on high speed craft. Macklin drew on his wide circle of business and technical contacts to form the Fairmile Marine Company, located at his country home ‘Fairmile’ in Cobham, Surrey. Macklin’s cleverly negotiated a unique arrangement with the Admiralty whereby Fairmile was to carry on business under an agency agreement and receive orders from the Director of Naval Contracts. Macklin would not be bound by Civil Service procedures, but no profit would be expected.

Seven hundred and three Fairmile MLs were built on 140 slipways in 45 UK boatyards while a further 180 ships sets were exported. The main Fairmile classes were A, B, C and D. Type A was largely experimental and only 12 units were produced; Type B was the first volume production – 383 boats. Bs were 112 feet long, displaced 85 tones and had an endurance of 1500 nm at 12 knots with 20 knots maximum. They served as Motor Torpedo Boats (MTB), Motor Gun Boats (MGB), rescue craft, navigation leaders (with enhanced radar fitments), minelayers and minesweepers. Ships companies comprised two officers, two petty officers and 12 – 14 ratings. Fairmile Cs were MGBs (24 boats only) and the next and final volume production were the Ds (229 boats). The main improvements to the D performance was a maximum speed of 34 knots due to four Packard 1250 hp supercharged petrol engines.

Fairmile ML crews suffered uncomfortably in heavy seas. The D series, with their sharp bow, steep flare, knuckle and rounded hull form aft were drier than the earlier versions. However, the wooden hulls ‘worked’ in head seas at high speeds which strained the hulls. ML habitability was sparse and uncomfortable for the ‘hostilities only’ crews. While they probably avoided the formality of ‘pusser’ ships and, in home waters, lived ashore at coastal forces bases, the noisy, wet and highly confined spaces required hardiness and dedication in the knowledge that their wooden boats afforded little protection in action.

The Harbour Defence Motor Launch (HDML) was not a Fairmile, but an Admiralty design. It was a wooden 72 feet long vessel, armed with depth charges, a gun and equipped with asdic (sonar) to provide anti-submarine protection in harbours and estuaries. Crews comprised two officers, two petty officers and six to eight ratings. HDMLs were produced in regular boat building yards using standard procedures rather than pre-fabricated kits. Four hundred and eighty-six HDMLs were built; nine served in the RAN.

The HDMLs were good sea boats and they saw service in most theatres of war, including south-east Asia. As with the Fairmiles, HDMLs were adapted to many uses which included as inshore minesweepers off the D-Day beaches and navigational leaders to guide the invasion landing craft. Conditions in HDMLs were no better than the Fairmiles. Appendix XII of the book: Service Summary HMIML 440 details the ship’s activities off the Burma coast describing the hot and cramped conditions and the dangers of covert navigation in support of special operations.

The US Navy SC 497 110-foot sub-chaser is the third major type examined in the book. The SCs were based on a similar 1917 World War I design to counter the expected submarine threat as the US was facing entry into the war. In 1938 the USN sought renewed designs from Elco and American Car and Foundry. The two prototypes, SC 449 and 450, were armed with a 3-inch gun and two depth charge rails. The boats’ performances were unsatisfactory, and the program was close to cancellation when General Motors offered its ‘pancake’ diesel which revitalised the project. The 2400 hp engine was twice as powerful and raised the speed to 22 knots with a range of 1200 nm at 12 knots. Eight hundred SC 497s were built with many transferred to the Soviet Union and France.

The undoubted strong feature of the book are the many hundreds of drawings of the MLs and their weapons, equipment and fittings. There can be no better source for such detailed technical coverage of these handsome craft for boatbuilder historians and modellers alike. Apart from the boats themselves, approximately half the book is dedicated to ML and SC weapons, radars, rocket flares, smoke floats and smoke-making apparatus and minelaying equipment and much more. The section on engines and engineering is particularly comprehensive.

While much of the ML weapons and equipment suites were practical and well-designed, the Holman Projector was not. The two-page description of this device tells us that it was a cheap stop-gap weapon operated by compressed air or steam. The device theoretically was to fling a Mills bomb at low-flying aircraft. The projector comprised a barrel about 4 ft 6 inches long, attached to a receiver and mounted so it could be trained through 360 degrees. The contraption was useless for its primary purpose; however, innovative ML crews found it an ideal weapon for firing cans, potatoes and the like at their colleagues in other boats when they felt the need to blow off steam.

John Lambert and Al Ross’ Allied Coastal Forces of World War II, Volume 2 is also being released by Seaforth Publishing. This volume deals with the dashing high speed British Vosper MTBs and US Elco PT boats. Stay tuned for more details of what was referred to back then as the ‘mosquito fleet’.