Sea Power and the American Interest; From the Civil War to the Great War. By John Fass Morton. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2024.

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

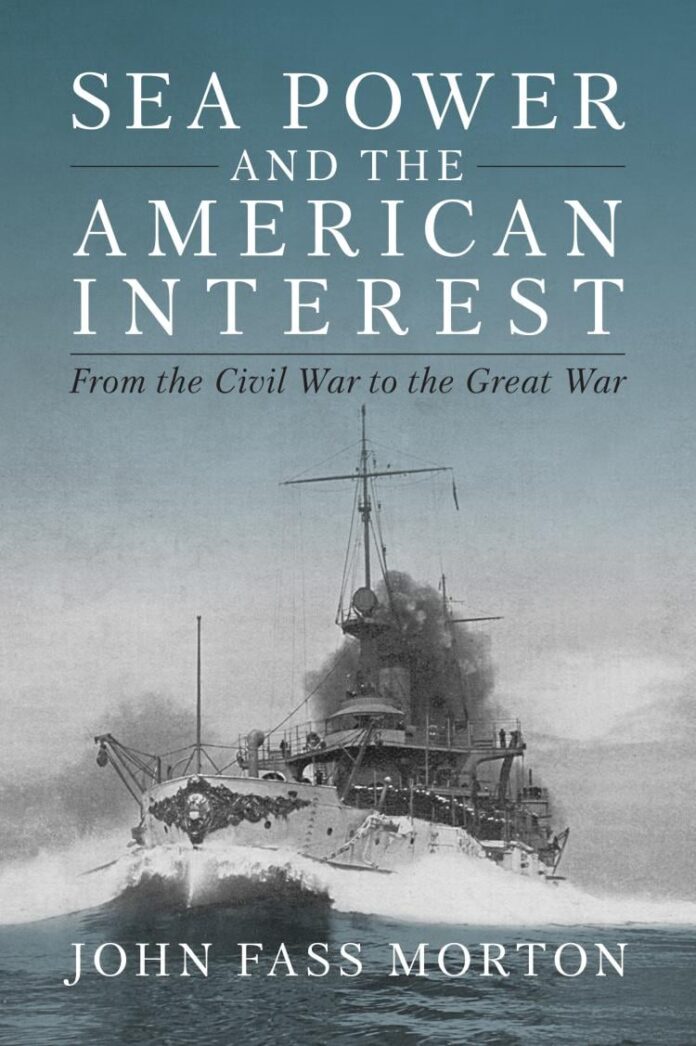

The cover of Sea Power and the American Interest depicts the USS Connecticut (BB-18) running trials in 1906. Belching smoke, its prow flamboyantly decorated with scrollwork, the white-painted battleship knifes through calm seas throwing up an enormous bow wave.

From December 1907 to February 1909, Connecticut joined 15 other battleships and attendant auxiliaries to encircle the globe in a demonstration of American sea power, grounded in its emergent diplomatic, economic, and industrial status.

At a cursory glance, the book’s title and its cover might appear to be another treatise on Alfred Thayer Mahan’s maritime strategic teachings and the transition from the US Navy’s post-Civil War torpidity to extra-regional line-of-battle capability. This impression would be erroneous as the book is far more than that.

John Fass Morton is a Washington DC-based national and homeland security consultant and regular contributor to defence publications, in addition to authoring several books. In Sea Power and the American Interest, he provides an economic and industrial history of the US through the ‘gilded age’ of the second half of the 19th century up to the Great War. From an antebellum agricultural economy, the Civil War was the catalyst for the postwar boom of Northern industrial capabilities, based on the development and production of steel and the discovery of enormous oil deposits. The unbridled entrepreneurship of JP Morgan, John D Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and many others, is recognised as the era of the ‘robber barons’, situated mainly in New York.

Post-revolutionary America was separated from the Old World politically and geographically. It had fought against imperialism but for the next century and beyond, a transatlantic commercial trading system was an American political-economic reality. This ‘Atlantic’ system saw European (largely British) investments in burgeoning US enterprises – most notably railways. At the same time, an ‘American’ system developed post-1812, largely emanating from the Southern states, which sought separation from Europe while America developed continental and hemispheric economic expansion.

The 1823 Monroe Doctrine opposed any intervention by external powers in the politics of the Americas; such interventions were to be viewed as potentially hostile acts against the US. This was the political-military declaration of US regional interests which laid the basis for ‘Dollar Diplomacy’. The US imposed its interest in the ‘Open Door Policy’ for access to China (in competition with the European powers). These strategic interests led to the realisation that a credible navy was essential to enforce the Doctrine and to support the expansionist economic policies.

Morton divides the book into three Parts. Part One: ‘An Industrial Republic in Pursuit of Expansion and Sea Power’ addresses the development of railways, communications, and banking. The Naval Observatory, established in 1844, conducted surveys in support of US interests in Latin America, the Pacific Northwest, and the opening of Japan.

Coincident with these surveys was the development of steel production – the essential element in railways and shipbuilding. This led to the ‘hemispherical American system’, from railroad development to the finance empires of the robber barons extending through the hemisphere and the Pacific to China and the demand for an ‘Open Door’ access.

Part One mentions the Navy peripherally, as American industries burgeoned. The Navy’s profile is more evident in Part Two: The Navy and the Progressive Institutions of the American Century. This details the discovery of abundant oil resources in the US and its potential for the Navy and wider national prosperity. The Navy takes centre stage in Chapter 14: In Search of a Twentieth Century Naval policy (this follows Chapter 13: From Respectable Defense to Preparedness for War; Toward a Peacetime Army – by which the army was transformed from plains warfighting to a peacetime standing army (possibly as a ‘projectile to be fired by the navy’ as British First Sea Lord ‘Jacky’ Fisher postulated in 1903).

In getting to grips with the US Navy, we are very much in the Mahan era – the American ‘prophet of sea power’ who advocated a powerful navy to protect maritime trade and assure national security domestically and abroad (reputedly Mahan’s signature work, The Influence of Sea Power on History 1660 to 1783, was ‘devoured’ by Kaiser Wilhelm II who ordered all his naval officers to read it). Rising from post-Civil War decrepitude, naval policy moved to acquiring an aspirational 48-battlehip US fleet over the latter decades of the 19th century. War Plans Black and Orange (against Germany and Japan respectively) were developed, and US naval power prevailed in the Spanish-American War of 1898.

President Teddy Rosevelt’s advocation of a navy ‘second to none’, was exemplified in the world circumnavigation by the Great White Fleet. Chapter 15 covers A General Policy of National Defense, in which the USN was prominent in asserting the American Interest, which was a shared Anglo-American Atlantic movement championed by influential navalists from industry and finance.

However, while the US Navy was emerging as a world-class fleet, the merchant marine had diminished to virtual extinction. The formation of the 1905 Merchant Marine Commission saw Government subsidies offered to shipping entities to both enhance trade and complement naval power to form a wholistic national sea power.

Sea Power and the American Interest is an important study of the rise of American sea power, as a component of the inexorable growth of American industry and commerce; it ranges well beyond the well-trodden Mahanian paths. Indeed, the book’s emphasis on American 19th century geo-economic development provides a comparative parallel to Mahan’s theories allowing readers to ground their overview of how and why the US Navy achieved its peer status by the onset of World War One. As such the book is an excellent aid to the student of US sea power.

For Australia, the realised creation of the ‘navy second to none’ had a tangible peripheral. The 1908 visit of the Great White Fleet to Australia supercharged the political will for an Australian navy. The Australian prime minister convinced President Roosevelt to route the Fleet to Australia (it wasn’t included in the original plan). Vast crowds turned out to see the Fleet, which exuded a mighty presence when compared to the anaemic ships of the Royal Navy Australia Station, which had formed a naval presence to the Australian colonies through the 19th century. As a newly federated Commonwealth, Australians were concerned by the emergence of Japan, with which Britain had concluded a naval agreement in 1902, ostensibly to dissuade regional Russian influence. This allowed the RN to withdraw assets from Asia to reinforce the Home Fleet. Australian lobbying succeeded against British opposition when First Sea Lord Admiral Jacky Fisher acquiesced to an ‘Australian Fleet Unit’, as a replacement for the RN Australia Station. When seven warships, led by the battlecruiser HMAS Australian, steamed through the Sydney Harbour Heads in October 1913, they were greeted by similar crowds as witnessed the Great White Fleet five years earlier. This birth of a nascent Australian sea power can be attributed, in part, to the influence of Sea Power and the American Interest.