A Discussion of the Value, Training & Future of the Australian Air Force Cadets, and a Short History of the Broader Cadet Movement in Australia

By Gary Martinic

Figure 1. Australian Air Force Cadets pictured at a promotion course graduation parade. One of the cadets is shown marching past while holding the AAFC National Banner.

Figure 1. Australian Air Force Cadets pictured at a promotion course graduation parade. One of the cadets is shown marching past while holding the AAFC National Banner.

SINCE 1941, tens of thousands of young Australians have undertaken training in an organization which was originally founded as the Air Training Corps (ATC), later (circa 1976) to become the AIRTC, and which since 2001, has been known as the Australian Air Force Cadets.

The AAFC, and its predecessor voluntary organisations before it, form part of the ‘air element’ of the Australian Defence Force Cadets (ADFC) Scheme, the other two Cadet services including the Australian Army Cadets (AAC) and the Australian Naval Cadets (ANC). Operating overwhelmingly as a volunteer organization, the ADFC today boasts approximately 27,000 young Australians aged between 13 and 20 years, and they are “supervised, trained and mentored” by a small volunteer, though professional force of some 2,600 Instructors of Cadets (IOC) and Officers of Cadets (OOC).1

Approximately 6,400 Cadets and 900 IOC and OOC staff comprise2 the AAFC service, which is administered and actively supported by the Royal Australian Air Force. Formed with the key aims of providing training in leadership, initiative and self reliance; developing an interest in aviation, history, Air Force knowledge and discipline, and in its widest sense developing Australian youth into responsible young adults with good character and citizenship qualities, the AAFC continues to successfully deliver these key aims, which it is likely to do well into the future. Many famous Australians, including former Prime Minister John Howard, champion golfer Greg Norman, popular actor Russell Crowe, Chief of the Defence Force, Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin, the former Chief of Air Force, Air Marshal Geoff Brown, and of course a host of famous career army officers of the past including Generals Sir Thomas Blamey and Sir Frank Berryman have been former cadets.3 This is not surprising since approximately 18% of the lower ranks of the ADF, and up to 50% of key senior officers in the ADF began their military careers serving in one of the branches of the ADFC.4

Despite being formed in wartime conditions from very modest beginnings, the AAFC has evolved to become a highly respected organisation due to its ongoing dedication, discipline, professionalism and a famous sense of ‘esprit de corps’. Despite the vicissitudes of its existence over 75 years, the AAFC (and the broader ADFC movement) have become important national institutions that have contributed much to the history of our country. We should be doing more to encourage the movement to grow even further as it clearly provides an ideal way forward for the youth of today.

History of the Air Training Corps

Formed with the aim of earmarking and providing pre-entry training for air and ground crews for the RAAF during WWII, the Air Training Corps was officially ‘born’ in February 1941, when the War Cabinet authorized the establishment of this new ‘Cadet Corps’ which was, during the interwar years, a part of the RAAF Reserve. It commenced operating on the 11th June of that year, under the leadership of its foundation Director, Group Captain WA Robertson (and a small number of Directorate staff).

Shortly afterwards, the ATC’s very first Wing was formed in August of that same year. By October, most of the states and territories of Australia already had their own Wings, which it should be said, was formed by a small group of dedicated volunteers most of whom were ex-WWI veterans (and many as members of the Royal Flying Corps or Australian Flying Corps) all of whom were now RAAF personnel. Its aims worked magnificently, in fact so much so that by October 1943, the ATC boasted some 12,000 cadets in training.

Aside from its key aims, there were also two very important objectives of the ATC, which were particularly focused on young men between the ages of 16 to 18 years whom were looking to join the RAAF, and they were (1) to inspire them and impart a sense of military discipline and comradeship, and (2) to educate and equip them with training and knowledge in areas which would be particularly useful to the inter-and post-war RAAF, such as aviation and technical studies. It is interesting to note that a significant number of ATC cadets did complete their training and went off to fight as air and ground crews in the war in Europe. A number did not return from the war.

By August of 1945, by the time the war in the Pacific had ended, the number of ATC cadets had dropped to just over 7500. A period of further demobilization and scaling down of the ‘cadet forces’ followed, particularly between the years of 1946 to 1948, and by December of 1949, total ATC numbers dropped to just 3,000 Cadets.5 Significantly however, the post war years did not just involve a scaling down of the organisation’s numbers but they also, importantly, redefined the principal aims and conditions of the organization, which were now primarily an ‘air youth movement’.

At the same time, and in the context of its peacetime role, it was also made clear that cadets were no longer obligated to enlist in the RAAF, but that ‘should they desire to do so, their enlistment would of course be welcomed’ by their parent organization. The post-war years leading up to the early 1970’s were defined as a period of mild to moderate growth, despite the fact that most of this was achieved by the goodwill of mostly volunteers, with some support of the ADF, and with little if any government support. It was also a period in which school-based and non-school based cadet units became more distinct.

Disaster was struck for the organization when in 1975, the ATC was officially disbanded by the-then Whitlam Labor Government. This was very heavily influenced at the time by a strong publicly-supported anti-war sentiment, owing to the horrors of the Vietnam War. Despite this massive drawback the ATC survived, mostly once again due to its strong base of RAAF reservists, volunteers and parents who gave generously of their time, and also financed many of its activities. Luckily for the ATC, the Fraser Coalition Government, which came into power shortly after the famous ‘dismissal’ of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, did see the benefits that the organization provided, and in 1976 it completely reinvigorated and reformed the ATC, although this now took the form of a largely ‘non-military’ organization.

During this year the ATC was also renamed the ‘AIRTC’. A few years later, in 1982 girls were encouraged to join the organization, and many were admitted. Over the next decade or so, the numbers of both cadets and staff members were dramatically increased, and in 1991 a national AIRTC organization on training was created for the first time.

Almost another decade followed when in the year 2000, the very first sign of enhanced government support was initiated with the important Topley Review.4 This review lead to the formation of the Directorate of Defence Force Cadets (DDFC) which was a Tri-Service policy support directive for cadets, and which included a $6m ‘Cadet Enhancement Program’. In 2001, the name of the AIRTC was again changed to the ‘Australian Air Force Cadets’. However, despite the new name change which seemed to suggest a nationally cohesive organization, there were eight separate ‘organisations’ operating based on essentially state political boundaries. Systems and standards of training across ground and air subject material varied significantly across state borders, and while both AAFC cadets and staff wore identical uniforms to the RAAF, they still were not totally actively supported by the RAAF.

This all changed when in April 2005 the AAFC was reorganized into operational and functional wings. A new Office of the Chief of Staff position was created to provide national policy with command authority, and also three functional wings were created which included the Ground Training, Air Training and Logistics Support Wings. Eight operational wings were also created on state boundaries, which were also redirected to provide service delivery and focus. These include: 1 Wing – North Queensland; 2 Wing – Queensland; 3 Wing – New South Wales; 4 Wing – Victoria; 5 Wing – Tasmania; 6 Wing – South Australia; 7 Wing – Western Australia and 8 Wing – Northern Territory.6

An Early History and Changing Fortunes of the Cadet Movement

The cadet movement has had a profound impact on many generations of Australian men and women. Many fondly remember the time they spent in uniform learning simple skills such as field craft, navigation, survival and first aid, as part of a popular movement that also developed important life skills such as initiative, confidence, self-discipline, leadership qualities, and of course a ‘team spirit’.3 4 During the years of WWII the instruction to cadets was more of a military nature, in which they were taught tactics such as defence and attack drills using weapons, often in an effort to make the training as ‘realistic’ as possible, and in the hope they would later go on to enlist into regular military service, which many did. Today, the cornerstone of the training is aimed at character development and ‘adventure-type’ training that fosters the qualities of leadership, cooperation and self-reliance.6

Originally formed with the intention ‘to train their boys for national defence in time of national emergency’ which at the time grew out of a fear of war with Napoleon III in the late 1850s, the very first cadet corps were formed at many famous English schools such as Eton, Harrow, Shrewsbury and Winchester.7 The (army) cadet movement as it was then, specifically focused on strict discipline, particular military skills, and ceremonial drill lessons. An ever-present fear of war with France in that period, as well as the popularity of rifle shooting competitions (which were used as an incentive move to encourage young cadets to join) actually helped the cadet corps to become very popular. Of course it wasn’t long before the cadet movement was established in Australia, with the introduction of the Commonwealth Military Cadet Corps.3 Essentially the cadet movement prospered until the depression years of the 1890s, when a number of schools were forced to close their units.7

The earliest records seem to indicate that the honour of being the oldest army cadet unit belongs to St. Mark’s College in Sydney, which was originally established in 1866, although many other units were similarly formed in Australia’s eastern and southern colonies. In contrast, the Naval Cadets were not established until the beginning of the 20th century.8 Many years later a resurgence returned to the cadet corps, in fact, compulsory cadet service was introduced in 1911, and Australian youth could serve either at school or community-based units, which in its first stage of enrolments peaked at around 100,000 cadets.3

Like many large scale organizations before it, the Cadets have suffered from financial hardships which have significantly impacted the movement. These have come and gone in many forms, for instance, many cadets left the corps when it became apparent that the army couldn’t supply enough uniforms due to the financial constraints of the great depression3 of the 1930s, which in itself is not surprising as only the year before, compulsory cadet service was abolished by the-then Labor government of James Scullin. In contrast, the government of Joseph Lyon’s conservatives did much to enlarge the movement due to better economic times of the late 1930s, and beyond. In fact, Sir Robert Menzies, Liberal Prime Minister of Australia, should be duly acknowledged with re-invigorating the cadet movement as well because under his leadership the numbers again increased by around 25%. Financial constraints were again a cause of a great reduction in the number of instructors in the cadet corps from the mid 1960s until the ‘infamous’ period of 1975 when school-based cadet units were disbanded.

Aside from financial considerations, the community also became increasingly uneasy about youth undertaking tactics and war-like training which many considered a form of ‘youth militarism’, especially at the time of the Vietnam War, hence there was a huge focus on relaxing the training of cadets. This was further attenuated when the Hawke Labor Government in 1983 again withdrew financial government support to school-based cadet units. It was not until 1998 that full support was restored to school-based cadet units, mostly thanks to a change in government, and to them adopting the Brewer report’s recommendations.8 Despite these setbacks, many regard the ‘golden period’ of the 20th century for the cadet movement as the time between WWII and 1975, as the numbers of cadets that were enrolled again peaked as high as 38,000 members.3

A Strong Program of Formal Training

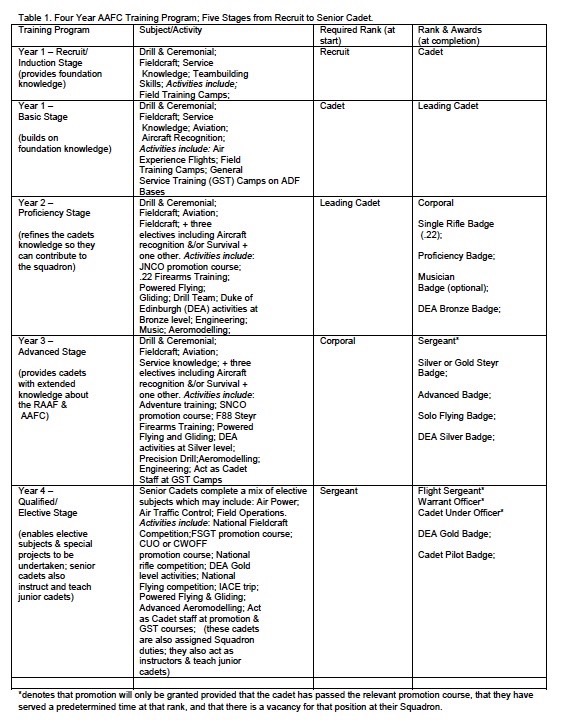

AAFC cadets undertake formal classroom instruction in a range of subjects during their weekly parade nights. Some of these include: military service knowledge, aviation, fieldcraft and survival, and drill & ceremonial. Each of these subjects are taught at four separate levels for example, recruit, basic, proficiency, and advanced. A detailed training program is provided in Table 1. Once cadets have passed advanced levels of training they are eligible to undertake specialist elective subjects which are normally undertaken as special projects. Additionally, highest rank cadets, such as Cadet Under Officers and Cadet Warrant Officers are able to accrue 2.0 ATAR points towards their Higher School Certificate studies, and also towards a Certificate IV level qualification in Frontline Management, gained during promotion courses.

The broad aim of AAFC Squadron training is to achieve the wider aims of the AAFC. In accordance with the AAFC Youth Development Philosophy,9 the senior cadets deliver much of the home training syllabus, often supervised by AAFC staff, who are trained in educational management and many other subjects. In addition, part 2 of the AAFC Manual of Ground Training10 specifically deals with AAFC Squadron training issues.

Table 1. Four Year AAFC Training Program; Five Stages from Recruit to Senior Cadet.

The AAFC training program, as above, is currently in use, however the ‘Vision 75’ report,11 which provides a future vision for cadet training in the AAFC, as well as the more recent ‘Draft Cadet Curriculum’ survey, and subsequent report,12 indeed highlight that training in the organization is on the cusp of change. It will be interesting to see how the AAFC syllabus changes in the near future.

Commonly offered Elective Subjects

Once core subjects are completed, senior cadets are offered ‘specialist’ elective subjects to study. These include but are not limited to; air traffic control, fire safety, radio communications, field operations, hovercraft technology, motor vehicle awareness, aircraft engines, meteorology, model rocketry, air navigation, basic visual tracking, and aviation weapons.

Types of Activities Offered

AAFC cadets are offered a broad range of activities to undertake which include remembrance marches and services; Anzac Day, Remembrance Day, Vietnam Veterans Day, and Servicemens Day. They are also offered opportunities to undertake weekend field exercises concentrating on survival in the bush, fieldcraft techniques, navigational exercises and leadership training.

Cadets can undertake and experience powered flying and gliding, firearms safety training, adventure training, aeromodelling, engineering (basic aeroskills), first aid courses, leadership training, air traffic control courses, musicianship courses, and the chance to experience exchanges to overseas countries with similar air cadet organisations (known the International Air Cadet Exchange program). From a team-building perspective, they are also regularly offered ‘fun’ activities such as white-water rafting, rock climbing, I-Fly (indoor parachuting), abseiling, caving, & a ‘ropes over water’ course at ADFA.

Flying – a cornerstone of the AAFC activities

The AAFC has always provided opportunities for flying activities to both its cadets and its staff members, in the form of both powered and gliding aircraft. The purpose of this has been to train and test members in aeronautical skills, and to help expose AAFC cadets to aviation training and flying skills in general. This was first introduced in the 1950s and was popular from the start. To this end, approximately 66 gliding scholarships and 20 powered flying scholarships are awarded every year in the AAFC, which are financed and supported by the RAAF. Many cadets and staff have achieved their training goals and their ‘wings’ in this way, and continue to train and mentor junior members who are also wanting to gain their own qualifications.

Recently, the AAFC has been very fortunate in that its parent organization, the RAAF, has provided the AAFC with the newest gliders to use in its training program. These are the ASK-21 Mi self-launching gliders and the DG-1001 Club soaring gliders (Fig.2) Eleven of each type of aircraft were officially handed over to the AAFC by the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Defence, Mr. Darren Chester, and the then CAF, Air Marshal Geoff Brown, in March 2015 at the Avalon Airshow in Victoria.13,14

All in all, this provides the AAFC with 22 new glider aircraft which have been supplied on a pro-rata basis across the Wings of the AAFC (excluding AAFC powered aircraft). AAFC cadets of 3WG (NSW) have also been very fortunate in that the RAAF has financed the construction and development of new aviation facilities in Bathurst NSW, which is regularly used by many squadrons within 3WG NSW, and more recently also used by the ADF.

Former Chief of Air Force, Air Marshal Geoff Brown pictured with Australian Air Force Cadets alongside one of the new DG-1001 gliders, at the Avalon 2015 Airshow (Photo courtesy of Australian Aviation magazine).

Comments from those who have served, on the benefits of Cadets

A huge majority of those whom have served in one of the branches of the cadets have only positive things to say about the movement. For example, an oft-quoted remark by many ex-members is how serving in the cadets has ‘transformed’ their lives for the better. Many whom have made this comment go on to explain that their ‘cadet experience’ has been extremely valuable to them because of the military-orientated training to build self-reliance, resourcefulness, endurance and a sense of service to the community.15

Many said they feel a part of ‘one country’, as the types of activities that the cadets regularly run promote and build a sense of teamwork and togetherness, often achieved not only via military-style bivouacs, but also through teamwork and bonding activities such as various sports, and even orchestras. These experiences work to set them up for success in later life and also provide many with a sense of patriotism.

Another ex-member of cadets recounted how the cadets didn’t just teach him how to be competent using a rifle, and how to navigate his way in the field from point A to point B without getting lost, but it also taught him how to think quickly in challenging situations. Most importantly, he states that it set him on the ‘straight and narrow’, making him understand right from wrong, and thereby instilling a sense of worth and respect for both himself, as well as others around him.15 This same person went on to contribute as an adult staff member for 17 years to ‘give something back’ to the cadets which had such a positive effect on his own life.

Another ex-army cadet fondly remembers the discipline, training and education that he was given, much of which he subsequently used during his 30 year long career in the regular army, and felt very strongly that similar opportunities should be provided to school-age teenagers of today. Another went on to a long and rewarding career in the RAAF (as did many others). This ex-member recounted that his very positive experience in the AAFC will stay with him for the rest of his life, and he concluded his comments by asking the question, ‘which other youth organization gives you the opportunities to learn to fly or glide, to compete in target shooting, to navigate in the field (including at night), to learn a musical instrument, or to participate in team sports?’15

It was also strongly felt that many of these ex-members of cadets had done more with their lives, than had they not been cadets, and that the friendships that were made during these formative years remained throughout their lives. Also it should not be forgotten that many of these ex-cadets went on to join the ADF and have long fulfilling careers, in which many were stood in good stead because of their prior cadet training.

Due to the high levels of discipline and personal responsibility that cadets maintain, many parents of serving cadets comment that they often see an improvement in their educational abilities as well as their sporting prowess, which they believe may be directly attributable to the nature of training that they receive.4,15

However, critics of the cadet movement often say that it is a form of ‘youth militarism’, which is only being used as a way to cure youth degeneracy.3 Whether one agrees with this statement or not, it is evident that cadet training generally does tend to have a significant degree of success when it comes to dealing juvenile delinquency and degeneracy.3 Moreover, with the contemporary issue of record levels of school age teenagers being suspended from schools for violent behaviour, 16 or for possessing illicit drugs, 17 it would seem logical that the cadet movement should be able to do a lot to improve the lot of our troubled youngsters.

The importance of quality adult staff mentors

The scale and scope of the cadet activities is only as good as the quality and calibre of the staff members who plan and implement them. It is no good having a myriad of interesting subjects which to learn, or activities in which to participate unless you have the staff who have the knowledge and experience to teach, train and supervise it.4,15 It is a well known fact that since 1976, the cadet movement has been fortunate to have been run mostly by RAAF reservists and a number of non-military adult volunteers, some of whom were ex-cadet personnel themselves.

Regardless, both groups provide a significant wealth of knowledge and experience which directly contributes to which ever class was being taught, or which ever activity which was being run. Also, it is interesting how quality staff can have a positive influence on cadets during their period of service.4,8,15 The consensus of many ex-members of the cadets often cite how it was the work of the adult staff which often set high standards, and inspired them to achieve ‘greater things’ and even to bring out their very ‘hidden’ talents, through their constant encouragement and mentoring. These same ex-members of cadets say they remain forever indebted to such ‘role model’ staff, for they probably would not have achieved as much in the cadets, and later in life, had it not been for such quality adult volunteer staff.4,8

Summary

Regardless of the changing fortunes of the AAFC and the broader cadet movement over time, it is clear that ‘cadets’ has been an institution which has touched the lives of a significant proportion of our population over the last nearly 150 years. It is also clear that throughout the history of the cadet movement there have always been four key areas, or ‘pillars’ as one author puts it,3 that have been vital to its operations in the past, and will likely do so in the future. These have been a combination of factors including important educational and community interests, financial resourcing, and the level of both government and military support, and their inherent outlook on the cadets. As has been evident in the past, any disproportion between these pillars will likely weaken the structure of the organization moving forward. Similarly, radical changes in decision-making and key government policy shifts away from support, will have disastrous effects on the movement, hence the need for an ongoing, reliable and stable platform of support, where all four pillars are maintained in equilibrium, is vital.

The question of the value of the cadet movement and the contribution it makes to national, military, educational and sociological settings has often arisen, which has prompted various studies and reviews into these movements in the past, both in Australia and overseas.18 For example, the Brewer study conducted in Australia,8 and two earlier studies, one from Canada19 and another from the United Kingdom20 have all led to the same general conclusion, that ‘government-sponsored school-age, military cadet systems are valuable’.

Another substantial Australian study by McAllister of the same period, and which assessed all three elements of the Australian Services Cadet Scheme of that time, also found that ‘by any standards, the ASCS is an important recruiting ground for the Australian military’.21 Huston,22 in his earlier research into the Australian Army Cadets saw the value of the scheme as it gave the cadets a foundation of military knowledge and discipline, developed leadership qualities, self-reliance and initiative, as well as sense of tradition which encouraged cadets to continue in some form of military service. While he felt that the training wasn’t sophisticated, it did provide a solid understanding of rank structure, barracks routine, discipline, fieldcraft skills and military organization, which placed ex-cadets at a significant advantage over non-cadets, who were undertaking training at either ADFA or the Royal Military College at Duntroon.

Furthermore, Huston argued that it was in his view, not only important to reinvigorate the Cadet Corps, but indeed to regularly maintain their numbers at high levels. He felt that this was important because of the inherent value that they bring to the ADF. In the end, he affirmed that this policy should be considered as an investment, rather than an expense by those in the senior leadership of the ADF.22

In this electronic age where video gaming and a sedentary lifestyle has resulted in record rates of obesity23 and other negative lifestyle issues24 in Australian youth, it has never been more important to engage Australia’s youth and make them aware of the wide range of healthy activities that the AAFC, and the broader ADFC can offer them from a developmental, physical and mental health perspective. The well-designed and rigorous training programs of the AAFC, and the broader ADFC, have proven over a long period of time that the ‘system’ works. Fortunately, these programs are still alive and kicking to this day, and for the benefit of Australia’s youth we should do all we can to encourage the movement to grow further.

Furthermore, with the 75th anniversary celebration of the birth of the AAFC due to fall in the year 2016, the AAFC is busy planning a myriad of ideas and activities for this important event which will mark three quarters of a century of service to Australia by this very important national movement. The senior national AAFC leadership are in the planning and coordination stages of exciting activities which will likely signify the nature of what the AAFC represents, such as massed formal parades of cadets and staff, coordinated flypasts of the AAFCs glider squadron, fieldcraft competitions, large-scale sporting activities, and even some international activities, such as the Nijmegen march in the Netherlands in July 2016, a ‘first’ for the AAFC, and indeed Defence. The Nijmegen International 4 Day March event is also celebrating 100 years, and in turn ties in very nicely with the AAFC 75th Anniversary. All of these events promise to not only be exciting and memorable, but to also lift the national profile of the AAFC even further.

-o-o-O-o-o-

In his civilian role as Laboratory Manager and supervising scientist, Gary Martinic manages the Centre for Infectious Diseases & Microbiology and the Marie Bashir Institute of Biosecurity & Infectious Diseases at the Westmead Institute for Medical Research. Wearing his ‘other hat’, Flying Officer Martinic also works as Training Officer-Operations, Firearms Quality Manager and Unit Safety Coordinator based at 307 (City of Bankstown) Squadron, Australian Air Force Cadets, located at Defence’s Multi-User Depot, Lidcombe NSW.

In his civilian role as Laboratory Manager and supervising scientist, Gary Martinic manages the Centre for Infectious Diseases & Microbiology and the Marie Bashir Institute of Biosecurity & Infectious Diseases at the Westmead Institute for Medical Research. Wearing his ‘other hat’, Flying Officer Martinic also works as Training Officer-Operations, Firearms Quality Manager and Unit Safety Coordinator based at 307 (City of Bankstown) Squadron, Australian Air Force Cadets, located at Defence’s Multi-User Depot, Lidcombe NSW.

With a lifelong interest in military aviation and military history, and having previously served for a number of years in the Air Training Corps, as a current serving AAFC Officer, he now dedicates his time to supervision, training and mentoring AAFC Cadets. He has a strong interest in unmanned weapons systems of land, sea and air, and has written numerous articles for both national and international defence journals and magazines, a few of which have received ‘Authors Awards’. He is also a prolific author on topics relating to in-vivo based biomedical research.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are extended to Dr. Matthew Glozier for his critical review of my manuscript, and for permission to reference information from his new book ‘75 Years Aloft: Australian Air Force Cadets (Royal Australian Air Force Air Training Corps), 1941-2016’, which is due to be published early in 2016. Secondly, I thank Mr. John Griffiths, MBE Director of the Alumni Association for his useful feedback and advice. Lastly, I thank WGCDR(AAFC) Paul Hughes, Officer Commanding 3 Wing AAFC, for his endorsement and helpful comments.

References

1. Air Commodore McDermott, Committee Hansard, 21 June 2004, p. 45 (Australian Defence Force Cadets).

2. Williamson, G. (2015) As quoted in the Preface to: Glozier, M. ‘75 Years Aloft: Australian Air Force Cadets (Royal Australian Air Force Air Training Corps), 1941-2016’. Canberra: Defence Publishing Service. Publication pending Jan. 2016. Pp xix, 428. ISBN 978-1-326-14299-5.

3. Stockings, C. (2007). ‘The Torch and the Sword. A History of the Army Cadet Movement in Australia, 1866-2004’. University of New South Wales Press, Sydney.

4. Topley, J. (2000). Section 1.14 Chapter 1 In: Cadets – the Future. Future Review. A Strategy for the Australian Services Cadet Scheme. Parliament House Canberra ACT.

5. Reserve Magazine (1949). Royal Australian Air Force Reserve Magazine. Vol 1, No. 2. RAAF Headquarters, Melbourne.

6. Australian Air Force Cadets website, see also:

7. Kitney, P. (1978). The History of the Australian School Cadet Movement to 1893. Defence Force Journal. No. 12 Sep/Oct issue.

8. Brewer, C.J. (1996). Review of the Australian Services Cadets Scheme. Chairman, Col C.J. Brewer, AM.

9. Australian Air Force Cadet document (2011). AAFC Youth Development Philosophy. Office of the Commander, AAFC National Headquarters, Canberra ACT.

10. Australian Air Force Cadet document (2006). Manual on Ground Training. AAFC National Headquarters, Canberra ACT.

11. Wozniak, J., and Young, S. (2014). Vision 75: Cadet Training Needs Analysis Discussion Paper 2014 – Brining AAFC Training from Spitfire to Unmanned Flight. Australian Air Force Cadet document, Canberra ACT.

12. Fechner, C. (2015). Survey Report: Draft Cadet Curriculum – Feedback Results, Analysis and Findings. Training Directorate, Australian Air Force Cadet document, Canberra ACT.

13. Parliamentary Brief (2015). Air Force Cadets receive new Self-launching Gliders. Report by the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Defence. Department of Defence, Australian Government, Canberra.

14. Australian Aviation, (2015) Australian Air Force Cadets presented with newest glider at Avalon. Mar. issue.

15. Mackenzie, C. (2012). Pupils on parade: Military-style Cadet Forces to be Introduced in all Secondary Schools (in the UK). Mail Online. See also:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2083832/Pupils-parade-Military-style-cadet…

16. Smith, A. (2014). Big Increase in Student Expulsions, Suspensions. Sydney Morning Herald, July 14th edition.

17. McDougall, B. (2015). Drugged Student Crisis in NSW schools: average 20 students suspended each week. Daily Telegraph, Feb. 9th edition.

18. Jones, W.H. (2000). Measuring the Value of the Australian Services Cadet Scheme. Australian Defence Force Journal. No. 140, Jan/Feb issue.

19. Canadian Forces. (1995). The DND/CF Cadet Program. Final Report on NDHQ Program Evaluation E3/93. Jan. 1995. Director: Skippon, P.C. (Miss). Canadian National Defence Headquarters Program Evaluation Division.

20. Lewis, C.A. (1995). The Air Training Corps Cadet and Staff Motivation Survey. Royal Air Force Research Report PTC/4961196/1/CSSB. Dec. 1995. Scientific Support Branch of Personnel and Training Command, RAF.

21. McAllister, J. (1995). Schools, Enlistment and Military values: the Australian Services Cadet Scheme. Armed Forces and Society. Vol.22.

22. Huston, J. (1991). The Australian Cadet Corps – Lost Opportunities. Australian Defence Force Journal. No. 89, August.

23. Brown, R. (2015). One Quarter of Australia’s Teenagers are Overweight or Obese, New Health Survey Reveals. ABC News, Feb 19th Edition.

24. O’Brien, S. (2013). Young Australians are Fat, Oversexed and Underemployed. Herald Sun, Mar 14th edition.

Images Used

Figure 1. Photo sourced from: Filename: 20130119raaf8194170_0020.jpg

Figure 2: Photo sourced from: An Australian Aviation magazine photograph taken March 1, 2015 at Avalon Airshow, Victoria.