On the morning of May 21, 1982, Lieutenant Commander “Sharkey” Ward was flying his Sea Harrier low over San Carlos Bay as British forces landed on the west coast of the Argentine-occupied East Falkland.

Under a clear blue sky, he flew in battle formation — side by side, two miles apart — with Lieutenant Steve Thomas, descending from the northeast and setting up “a low-level race-track patrol in a wide shallow valley”, helping to protect the British ships below.

At the southerly end of the track, as the two pilots completed their turns, Ward, as he recalled in an interview later, “spotted two triangular shapes approaching down the far side of the valley under the hills from the west”.

The objects were Daggers, the Israeli version of the French Mirage fighterbomber operated by the Argentine air force, and they were moving fast.

Ward levelled out of his turn and pointed directly at them, increasing power to full throttle, and alerting Thomas to the presence of the enemy jets. “My voice was so excited and garbled that Steve could not understand a word,” said Ward.

He flew between the Argentine aircraft, lower than the leader and higher than the No 2, as they flashed passed his cockpit. He expected the enemy jets to press on to their target. In the face of the Harriers, however, the Daggers turned for home — but it was too late.

Thomas came up behind the Argentine jets and destroyed two of them with Sidewinder missiles. Ward shot down a third, which entered the fight from the north and, as he found out later, had been firing at him.

“Adrenaline running high, I glanced round to check the sky about me,” Ward said. “Flashing underneath me and just to my right was the beautiful green and brown camouflage of the third Dagger.

I broke right and down towards the aircraft’s tail, found the jet exhaust with my Sidewinder and released the missile.

“It reached its target very quickly and the Dagger disappeared in a ball of flame. The engagement had lasted for roughly a minute and, although it all happened incredibly fast, in my mind it was registered as spectacular slow motion.”

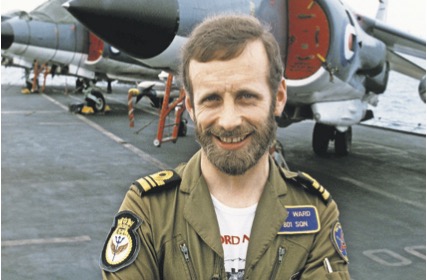

Ward was the commander of 801 Naval Air Squadron, which was based in HMS Invincible. The aircraft carrier was one of two — the other was the Task Force flagship HMS Hermes — sent to the South Atlantic after the junta in Buenos Aires had ordered the invasion of the Falklands, a British territory, on April 2, 1982.

A pugnacious and aggressive fighter pilot, Ward was often compared to Douglas Bader, one of the heroes of the Battle of Britain, and Albert Ball, one of the great aces of the First World War.

Like them, he was courageous and fearless.

He was also a fine squadron commander with strategic vision.

He had been involved in the development of the Sea Harrier, a naval version of the revolutionary “jump jet”, and played an important role in ensuring that it was highly capable in air-to-air combat. By the time 801 Squadron was sent to the South Atlantic, his pilots and their aircraft were more than a match for the Argentinians. On May 1, their first day in action, they demonstrated their deadly prowess, shooting down two Mirages and a Canberra.

Ward was a demanding leader who feared no one in authority and was quite prepared to confront his own side too.

He challenged Rear-Admiral Sandy Woodward, commander of the Task Force, over his conduct of the air war, and disobeyed directives from the flagship.

In short, he fought his own way.

His behaviour followed a rebellious pattern that marked his life — and paid off. As a child he was “the most caned boy at Reading School”, but still became head boy.

After passing through operational flying training with distinction, Ward was court-martialled in 1969 for an “exhilarating flight” in a Sea Vixen at extremely low level over the north coast of Devon and Cornwall. Members of the public rushed to complain and one newspaper ran the story under the headline: “Terror pilot frightens children.” He received a formal reprimand but was soon selected as an air warfare instructor.

He was posted to the Ministry of Defence in 1976 as the naval staff officer responsible for the development and production of the Sea Harrier. “The modification from the already well proven ground attack Harrier was a design masterpiece,” said Ward, who was involved in the project for three years.

In an interview with the aviation magazine Hush-Kit, he said: “It included a raised cockpit, a superb albeit physically tiny mono- pulse radar, the Blue Fox, a very reliable inertial standard navigation system and a very user-friendly head-up display weapons aiming system, including a hotline gunsight.

“The only guidance I received from my director was that if I wished to spend more than £5 million over and above agreed project costs, then I should clear it with him. But there was no need. It was the first UK fighter jet programme in history to be on cost and on time.”

Ward later commanded the squadron that took the Sea Harrier into “Top Gun” trials with American F-5E Tigers and F-15 Eagles. The Harrier dominated the exercises and was delivered to British naval squadrons in 1979, three years before the Falklands conflict.

Ward was awarded the Air Force Cross.

In a publicity stunt in autumn 1979, he landed the new jump jet at the BBC’s Pebble Mill Studios in the centre of Birmingham after the RAF had declined to perform the manoeuvre, saying it was too dangerous. He was soon known as Mr Sea Harrier.

In the Falklands his expertise was invaluable, but sometimes divisive. While 801 Squadron flourished with the aircraft in Invincible, 800 Squadron in Hermes was apparently less confident with the equipment. “They didn’t know how to use the radar properly or the navigation computer,” Ward said in an interview with the Imperial War Museum in 1986. “They weren’t at the same professional standard and this came out before the Falklands.”

Even by the measures of inter-squadron rivalry, this was harsh, but Ward stuck by his opinion and enlarged on it after the conflict. He said he had offered to share his expertise but was rebffed. In return, Ward was accused of “bullshitting”.

Influenced by the views of 800 Squadron on board his ship, Sandy Woodward restricted the use of the Blue Fox radar and ordered the Harrier squadrons to perform combat air patrols at high level.

Both directives were ignored by Ward. His squadron flew at low level, which enabled them to intercept enemy aircraft before they attacked the British ships. He made extensive use of the radar, which, he claimed, worked well and deterred the Argentinians. When they picked up signals from the Harriers’ radar, they held back and avoided the British aircraft. Indeed, the Argentinian pilots referred to the Harrier as “La Muerta Negra”, the Black Death.

Ward claimed that the sinkings of HMS Ardent and HMS SheZeld were avoidable and that long-distance Vulcan raids on the runway at Port Stanley were unnecessary. He believed that the airfield could have been destroyed by the Harriers flying at night, but the idea was dismissed, even though 801 Squadron had, without formal authorisation, completed a successful programme of night flying.

Ward flew more than 60 combat missions in the Falklands and shot down three of the eight enemy aircraft destroyed by 801 Squadron, which is believed to have turned away more than 450 enemy attacks. He damaged another Argentine aircraft and was involved in several more “kills”. The unit lost four aircraft and two pilots, but none in air-to-air combat.

Ward was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his “gallantry and devotion to duty”. He was also made a Freeman of the City of London and a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society. Years later, Woodward wrote: “If Sharkey Ward had not disobeyed orders, we would have lost the Falklands war.”

Nigel David Ward was born in Medicine Hat in Alberta, Canada, in 1943, the son of Squadron Leader John Ward, who was serving with the RAF in Canada, and his wife, Margery. He had an elder brother, Michael, and a younger sister, Anna.

He said his epitaph would be: Thank God he lived, thank f*** he’s gone

As with many naval personnel named Ward, he was always known as Sharkey after a 16th-century pirate. He changed his surname to MacCartan-Ward by deed poll in the 1990s in honour of his father’s Irish ancestry.

The family returned to Britain by sea in 1944. Ward suffered from a serious lung condition at the age of five and was confined to a hospital bed for a year. He only started to thrive after spending three years in Pakistan, after his father was posted to RAF Mauripur in Karachi, where his health improved in the dry climate.

In 1954 he was sent to Reading School in Berkshire. There he captained the 1st XV and learnt to fly in a Tiger Moth on an RAF scholarship.

He first set foot on an aircraft carrier as a teenager during a visit with his father. “I couldn’t get my head around how the huge glistening jet fighter aircraft on show for the cocktail party could operate from such a small deck,” he said.

“I knew then what I wanted to do.”

He trained at the Britannia Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, played rugby, took charge of the Tiger Moth Flying Club and, in his own words, “had a wild year as a midshipman in the West Indies and a rollercoaster ride as a navigator on minesweepers in Hong Kong”.

He was contemptuous of many rules and his philosophy was, quite simply: “Work hard, play hard.”

He later flew Phantoms from HMS Ark Royal with 892 Squadron and served as a nuclear intelligence oZcer in Norway for two years before returning to his squadron. He was given command of 801 Squadron in 1981.

Ward’s private life was complicated.

He met Alison Taylor, who was serving with the Women’s Royal Naval Service, in 1971 and married her in Gaddesby, Leicester, that year. The couple had two sons: Kristian, who also became a distinguished naval fighter pilot and served in Afghanistan, and

Ashton, who founded a head-hunting firm. The pair divorced in 1986. He is survived by Alison and Ashton. Kristian took his own life aged 45, after suVering from combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder (obituary, December 28, 2018).

His death aVected Ward hugely.

After leaving the navy in 1985, he set up his own company, Defence Analysts, which employed former members of the special forces to defend oil tankers during the Iran-Iraq War. He then moved to Turkey, where he started to build a hotel and married a local woman, Semiha Mutlular, in Marmaris.

Both ventures eventually failed.

In 1994 he moved to St George’s in Grenada after rescuing an English woman, Abbi May, from an unhappy marriage to a Turkish man, which involved an infamous bandit in the getaway.

His marriage to her did not last. His fourth and final wife was Mary Egan — the union was described as “brief”.

A generous spirit, Ward spent much of his later life helping Grenadians who had fallen on hard times and rescuing badly treated dogs, including a “dying” puppy found outside a church. He nurtured the dog back to health and named him Vicar.

As a boy he had listened to his father, a fine singer, and became a great fan of the Three Tenors, whose music could often be heard from his balcony in Grenada as he drank rum and Coke. He wrote three books: an autobiography, Sea Harrier Over the Falklands (1992), Her Majesty’s Top Gun and the Decline of the Royal Navy (2020), and most recently, How Strategic Air Power Has Changed the World Order (2024), with Dr Anthony Wells, a specialist in naval intelligence.

Ward argued that governments had spent too long paying lip service to naval aviation and wasted billions on land-based fighters and bombers for the RAF. Long after leaving the navy he became close friends with Woodward and campaigned with him for a change in defence strategy. Needless to say, the RAF long regarded him with suspicion.

Asked by an interviewer some years ago what he thought would be his epitaph, Ward replied: “Thank God he lived, thank f*** he’s gone.”

Commander Nigel “Sharkey” MacCartan-Ward, DSC, AFC, naval fighter pilot, was born on September 22, 1943. He died of a suspected heart attack on May 17, 2024, aged 80