By April A. Herlevi*

The fate of the subsea environment and the seabed are on the brink of a fundamental shift. Driven by the Trump administration’s recent sweeping changes to US national security and foreign and domestic policy, the increasing likelihood of seabed resource extraction is prompting serious commercial interest. (From The Interpreter. The Lowe Institute.)

Several of the intersecting policies mean the ocean floor has the potential to become more congested, testing international law and efforts to manage the seabed for the “benefit of mankind”.

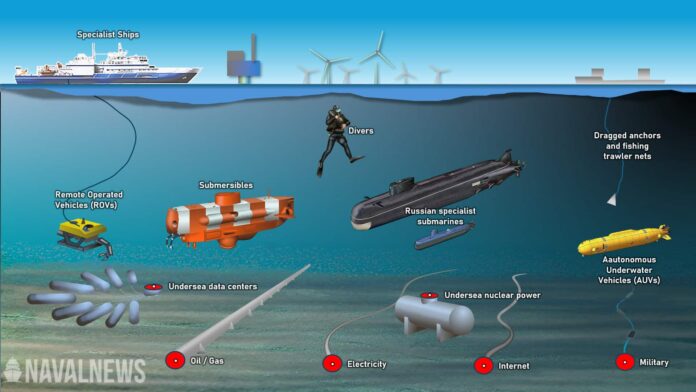

In the past four months, the Trump administration has published more than 130 executive orders. Three categories of emerging policy – maritime strategy, energy, and critical minerals – are likely to impact the seabed. Deep-sea mining and exploration, for example, combined with offshore energy projects, may lead to conflicts and what is known as “maritime spatial squeeze”. On the upside, shipbuilding plans could enhance subsea cable resilience if repair and maintenance ships and their associated workforce are part of the strategy.

Maritime reindustrialisation has bipartisan support in the United States, as does shipbuilding.

The new US policies have emerged to compete with China’s aspirations in the maritime, digital, and undersea domains. President Donald Trump’s 9 April executive order, titled “Restoring America’s Maritime Dominance” states that “it is the policy of the United States to revitalise and rebuild domestic maritime industries”. Maritime reindustrialisation has bipartisan support in the United States, as does shipbuilding. The president has ordered a Maritime Action Plan with inputs from across other agencies be delivered by 5 November.

The maritime dominance executive order also demands that the US Trade Representative “make recommendations regarding China’s anticompetitive actions within the shipbuilding industry”. Should this set of programs be enacted, the initial focus will be US Navy shipbuilding, but expansion of the sector could also provide a venue for increasing the supply of submarine cable repair and maintenance ships. According to one industry representative, as demand for telecommunications infrastructure continues there will likely be increasing demand for ships that lay cables and conduct repairs.

Of importance will be whether Trump reintroduces the Cables Security Fleet (CSF), which was initially established in 2019 to secure domestic capability to repair and maintain submarine cables. However, the CSF was defunded by the Biden administration in 2024, and the project’s future is uncertain.

Besides maritime policy, the White House wants “to make America energy dominant” and “expand all forms of reliable and affordable energy production”. As part of the energy security agenda and efforts to increase the availability of critical minerals for the defence industrial base, the administration released “Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources” as a follow-on to other mining-related executive orders. The order lays out the Trump administration’s goals, strategies, and legal arguments for seabed mining. In late March, The Metals Company (TMC), a Canadian enterprise based in Vancouver, issued a press release stating the company had applied for permits “to enable exploration and commercial recovery of deep-sea minerals in the high seas”, specifically in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean.

According to the International Cable Protection Committee, “uncoordinated deep seabed mining” poses significant risks for damage to submarine cables. Moreover, commercial actors, encouraged by the new deep-sea mining policies, and using US domestic law as justification, have the potential to further fray international institutions, making it difficult for the International Seabed Authority to manage exploration or exploitation of seabed mining in the high seas.

The push to begin deep-sea mining may frustrate US allies who have called for a “precautionary pause” or moratorium.

The extent to which Trump’s new executive orders are implemented is yet to be determined, but there are pros and cons in each. On one hand, increased demand for telecommunications will boost demand for cable installation, repair, and maintenance ships. If the Trump maritime policies can be turned into actionable steps for shipbuilding, likely with partners such as Japan and South Korea, then the anticipated cable repair shipdemands could be alleviated.

On the other hand, the push to begin deep-sea mining may frustrate US allies who have called for a “precautionary pause” or moratorium, arguing that forging ahead could disrupt regional relations in the Pacific or weaken international institutions, such as the International Seabed Authority. These potential outcomes could make coordination of subsea cable security policies more difficult.

The next key indicator to watch will come in late June. The Offshore Critical Minerals executive order states that the US government, via the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, shall “expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits”. If the US government grants TMC permits in June, then commercial interests are likely to drive domestic, regional, and international debates with a new sense of urgency.

*April A. Herlevi serves as senior research scientist at the non-profit research organisation CNA, and non-resident fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR).