Over the past five years, numerous articles have called for increased U.S. defense resources focused on the Arctic. This is a strategic mistake, a distraction.

This article will outline the reasons proponents feel the high north has increased value, examine the actual strategic value of each, and show that none is sufficient to divert scarce resources from higher value theaters. (From: The Center for International Maritime Security.)

Strategy should serve as an appetite suppressant to keep the nation from committing to peripheral missions at the expense of critical ones.1

The 2024 Department of Defense (DOD) Arctic Strategy was justifiably “prudent and measured,” limiting DOD actions to enhancing domain awareness, communications, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. It planned to work with Allies and partners to uphold deterrence and homeland defense.2 The 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy did not mention the Arctic.3 In contrast, proponents agitate for the United States to dedicate increased defense assets to maintain access to its vast natural resources, exploit the increased economic and shipping opportunities, and provide for national defense.

Unfortunately, the Joint Force is already overtasked in trying to meet its global and domestic missions while rebuilding the force. It is therefore prudent to examine the actual value of the far north before committing scarce resources to what is, at best, a strategic distraction.

A potential new trade route

The most exaggerated claim concerns the value of the Arctic as shortened and hence cheaper shipping routes between Asia and Europe. Many stories tout the speed and value of the shorter route for Asia to Europe shipping.4

While factual, these stories exaggerate both the volume and the value of shipping using the northern routes. To evaluate the real value of these routes, it is essential to understand their current usage and the limits that geography and oceanography impose. Figure 1, below, illustrates both routes.

The Congressional Research Service notes:

“The Northern Sea Route (NSR, a.k.a. the ‘Northeast Passage’), along Russia’s northern border from Murmansk to Provideniya, is about 2,600 nautical miles in length…Most transits through the NSR are associated with the carriage of LNG from Russia’s Yamal Peninsula…The Northwest Passage (NWP) runs through the Canadian Arctic Islands…potentially applicable for trade between northeast Asia (north of Shanghai) and the northeast of North America, but it is less commercially viable than the NSR.”5

While this description sounds promising, it is important to understand the current and potential flow of shipping, the nature of containerized shipping, and the impact of oceanography on its future growth.

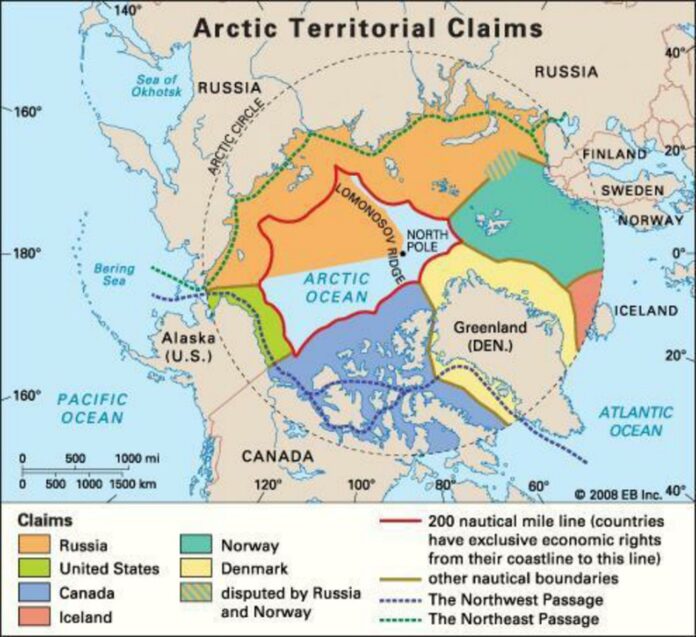

Almost all of the Northwest Passage lies within Russia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Russia also claims that key straits on the route lie within its internal waters.6 See Figure 2, below.

The percentage increase in shipping along these routes may sound very impressive, but only because the baseline was miniscule. Actual shipping remains minimal. The Centre for High North Logistics recorded only 97 voyages on the NSR during 2024.7 See Figure 4, below.

Despite continued official Chinese and Russian efforts to promote the route, as of August 31, 2025, only 52 vessels had transited the NSR. Container freight represented only 20 percent of the total. See Figure 5, below.

Further restricting traffic growth, in October 2025, four of the world’s five biggest container shipping companies — MSC Mediterranean Shipping Company, A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S, CMA CGM SA and Hapag-Lloyd AG — stated they will not use the NSR due to environmental, safe navigation, and transit issues. The fifth company, Cosco Shipping, a Chinese company, has not made a statement.8

The Northwest Passage supports even less shipping than the NSR. As the 2024 shipping season concluded only 18 ships completed the full journey – eight cruise ships, nine cargo ships and one tanker.9

Factors restricting the value of shipping via NSR or NWP

Several major and enduring factors – draft restrictions, unpredictable sea ice, the requirement for ice breakers, and higher cost per container–reduce the economic viability of these routes.

Draft restrictions

Arctic hydrography is particularly restrictive for commercial shipping. The NSR has a controlling draft of 12.5 meters and the NWP is limited to 10 meters. This means the Panamax-class (5,500 TEU maximum) is the largest that can use the NSR but they draw too much water for the NWP. In addition, ships may not have a beam of more than the ice breaker escorting them, or about 30 meters maximum.10

In August 2025, the NEWNEW company proudly announced it had increased its NSR traffic from 7 voyages in 2024 to 13 voyages in 2025. In those 13 trips, it carried a total of around 20,000 TEUs.11 For comparison, the Inira-class carries over 24,000 TEUs on a single voyage. From January 2022 to April 2024, over 800 ships per week transited the Cape of Good Hope and Suez Canal,12 for a yearly total of over 41,000 transits. More ships pass the Cape every 11 hours than use the NSR in a year and many are much larger than the Panamax-class.

Unpredictable Sea Ice

While Arctic Sea ice is steadily receding, this does not mean passages are necessarily or predictably clear. Sea ice moves with prevailing currents with thicker multi-year ice moving into areas where one year ice has melted. As such, moving multi-year ice often stacks up in restricted waters. The NASA image (Figure 6 below) shows how the melting ice on the NWP flows east and closes the route despite major reductions in total ice coverage. It led NASA to conclude:

“Despite overall declines in the thickness and extent of Arctic sea ice, shipping routes along the northern coast of North America have become less navigable in recent years.”13

The fact that the sea ice floats means it is very difficult to predict exactly where the passage will be blocked. This problem is not limited to the NWP. As late as September 2025, “a non ice-class Suezmax oil tanker has been forced to wait several days due to ice conditions before proceeding along Russia’s Northern Sea Route…at very slow speeds in close proximity to the shoreline to find a route through the ice.”14 Even ice rated ships are often delayed, the Buran, an Arc4 rated Liquid Natural Gas tanker “reached the Northern Sea Route north of the Bering Strait on October 29 and for the past three days has been struggling to find a path through early winter sea ice.”15

Compounding the problem of drifting ice, the routes have notoriously shallow water. The channels are not well marked and still surprise mariners. On September 7, 2025, the Thamesborg, a Dutch bulk freighter, ran aground in the remote Franklin Strait of the NWP. It required three salvage ships to refloat the Thamesborg.16 The vessel was not unloaded and refloated until October 9 – a delay of 33 days. Canadian Coast Guard inspections also revealed damaged ballast tanks.17

In addition to ice, Arctic weather ranging from storms to heavy fog often slows transiting ships. While delays are not a significant problem for bulk shipping, they have major impacts on the timeliness required for container freight.

Icebreaker requirements

Paradoxically, as the arctic ice cap is melting, the demand for icebreakers is surging. Russia has 47 in service with 15 under construction. Canada is funding two dozen new ones. Both nations require numerous ice breakers to support domestic industries in their EEZs.

In contrast, the United States currently has two icebreakers with one of those used primarily as a research vessel. The U.S. Coast Guard has also purchased a used icebreaker and hopes to have it in operation by 2026.18 Although the Coast Guard analysis indicated it would only need three heavy and three medium icebreakers, on October 10, 2025, the Department of Homeland Security announced the United States and Finland have signed a Memorandum of Understanding for a Finnish company to produce four icebreakers with the next seven being produced in U.S. shipyards.19Given only 18 NWP passages in 2024, it is unclear why the United States needs to increase its icebreaker fleet from two to 11.

Cost

Proponents of Arctic shipping routes note that shorter northern routes will mean lower costs. Unfortunately, several factors mean the cost of shipping individual containers will often be higher. Draft restrictions, lack of ports enroute, slow emergency response, stricter construction requirements, specialized crew training, ice breaker escorts, and insurance costs all contribute to higher cost per container. While the cost of an individual ship’s voyage may be less on a shorter route, the Thamesborg and Lynx show a shorter route does not necessarily mean it is cheaper or even faster.

Bulk cargo is usually shipped point to point so can benefit from a shorter route. Obviously, it makes sense to ship coal, LNG, and oil that is produced in northern Russia to China or India via the NSR. However, due to economies of scale, bulk cargo originating elsewhere may be cheaper to ship via the much larger ships that can transit southern routes. Not only are Arctic-capable ships much smaller, but they must also meet strict construction, outfitting, and crew training requirements which make them more expensive to purchase and operate. Due to the route hazards, insurance rates are also higher. Further inflating the cost per voyage is the requirement for ice breaker escorts. Both Canada and Russia charge each vessel for icebreaking services.20

For its part, container shipping has different cost factors. The most important metric is the cost per container rather than the cost of the voyage for an individual ship. Thus, scale is an important factor.

A second critical metric for container freight is timeliness. Unlike either northern route, southern routes can be part of a shipping network. This is critical for on-time delivery and economy of scale. The desired standard for on-time delivery for containerized freight is 99%. To achieve this goal, container ships operate in networks with “strings” or routes of many ports serviced by multiple ships on a steady schedule. For example, a US east coast to Southwest Asia route taking 42 days round trip serviced by six ships means regular weekly service out of the ports serviced on that route.21

The network described limits delays to a week. Today, much of the global economy consists of subcomponents built in one country, shipped to a second for final assembly of the subcomponents, and then on to another country for inclusion in the final product. Such supply chains are based on just-in-time delivery. As the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated, failure to deliver on time means production lines must be idled, making reliable delivery time critical. As noted, the unpredictable sea ice, infrequent sailings, and often brutal weather on the northern routes reduce reliability. Given the northern routes cover 2,500 miles with minimal infrastructure or support services, weeks-long delays are not unusual.

Access to natural resources

Minerals, particularly those yielding rare earth metals, are often touted as the primary resources of interest in the north. In fact, the Geological Survey of Norway estimated the value of rare earth minerals in the Arctic alone is $1.5-2 trillion.22 However, most of the minerals lie within the Exclusive Economic Zones of the six nations bordering the Arctic — Russia, Norway, Denmark, Canada, the United States, and Iceland. Any exploitation will be done by those nations, and so there is no special urgency to secure them against competitors. Figure 3 shows how only a small slice of the Arctic Ocean lies outside national EEZs. A paper from the Institute for Security & Development Policy also noted:

“Overall, the High North’s … resources have long attracted global interest, but their exploitation is technologically difficult and capital-intensive, and often faces local resistance due to risks to nature-based livelihoods and cultural heritage. … In short, the Arctic’s mineral wealth is both enormous and yet largely untapped…”23

Just as important, rare earths are not rare. The High North is estimated to hold only 15 percent of the world’s supply.24 In fact, in the last year major deposits have been found in Wyoming and Arkansas; these deposits have the obvious advantage of easier access. The issue is not the ore but the refining process. Currently most rare earth minerals are shipped to China for refinement into rare earth metals. If the United States continues to invest in refining facilities, supplies of rare earths will not be an issue.

Oil is another driver of interest. According to the U. S. Geological Service “roughly 22 percent of the undiscovered, technically recoverable fossil fuel resources in the world” may remain in the Arctic with 84 percent of it outside the Exclusive Economic Zones of Arctic nations.25

However, the high production cost of High North oil meant the United States government received no bids in the January 2025 Alaska Wildlife Refuge lease sale.26 Apparently, oil firms have decided it makes no economic sense to invest in very high-cost production when there is still oil in fields with much lower production costs. Russian firms are the obvious exceptions. As state-controlled firms, they must continue to invest onshore in the north of the country. Oil revenues are essential to the Russian economy and government budget.

National Security

Two threads emerge from the discussion of the need for U.S. defense of the High North. The first is the need for surveillance to detect any Russian attack coming over the pole. The second concern is the security of Greenland, Svalbard, and the protection of shipping routes.

During the Cold War, the United States and Canada operated the Defense Early Warning (DEW) radars from 1957 to 1985 to provide warning of Soviet bomber and missile attacks over the pole. From 1985 to 1988, DEW transitioned to the North Warning System (NWS). The NWS provides surveillance for the atmospheric defense of North America. Today, the United States and Canada are working to improve the surveillance element of missile defense. Re-establishing the radar system in the High North will be an extremely difficult, very expensive, and time-consuming project.27 A potential alternative is space surveillance. The Pentagon is already exploring deploying space-based sensors as part of the Golden Dome. If this very expensive project continues, it will provide the surveillance aspect of the DOD tasks.

The sudden concern that the United States must field and deploy forces to physically defend Greenland, Svalbard, and the new shipping routes is a bit puzzling. By holding the Greenland-Iceland-UK Gap, NATO credibly defended the western exit from the High North throughout the Cold War against a highly capable Soviet Navy. Even with global warming, the Gap will remain Russia’s best exit to the west. In the east, the Bering Strait is about 50 miles wide with two islands in the middle.

In fact, the most significant change since the Cold War has been the steady decline of the Russian forces in the region. “Decades of attrition, neglect, and resource depletion have left Russia’s Arctic capabilities outdated and functionally broken.”28 Against the degraded Russian air and sea forces, land-based missiles and drones can provide an affordable option. There is no requirement for U.S. or allied forces to penetrate the NSR. Containerized land-based missiles, drones, radar, command and control systems integrated with space-based surveillance can allow U.S. and allied forces to engage surface ships and aircraft transiting the Arctic. In short, the United States and its allies can control traffic that attempts to leave the Arctic. These systems can also support the most challenging mission – tracking and, if needed, engaging Russian submarines.

Conclusion

Strategy should provide discipline to guide the investment of limited defense resources. Proponents of investing in capabilities focused on the High North point to defending Greenland and Svalbard; balancing the increased Chinese and Russian interests in the region; maintaining access to its vast natural resources; and taking advantage of the shortened shipping via the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage. Yet, the vastly increased range of land-based missiles supported by pervasive surveillance means it is easier and cheaper to defend the chokepoints at the exits to the Arctic Ocean than during the Cold War. And they will do so against vastly reduced Russian forces. The vast natural resources lie within the EEZs of the Arctic nations, so access requires diplomacy and businesses willing to make arrangements for western firms to exploit them. Military resources will not improve access. Finally, the shipping routes will, even with massive growth, never amount to more than a minor fraction of global trade. So, while there is some value in investing in High North capabilities, those resources will have to be taken from already under-resourced theaters with much higher strategic value. Strategy requires allotting scarce assets to priority missions – the High North is not one of them.

While there is essentially no need for major military investment in the High North, the United States should continue to engage concerning environmental issues and apply sanctions against violators. It should also reduce its icebreaker contract to the maximum of six suggested by the Coast Guard. While the current two icebreakers may be insufficient, the proposed buy is much too large. It will take shipbuilding resources away from the Navy at a time when the fleet is understrength and has no path to sufficient numbers of ships. The U.S. can continue to maintain a defense of the High North using the same terrain and maritime chokepoints used during the Cold War. The investments in new generations of cruise missiles and long-range drones necessary to support the priority theaters will also provide a flexible force to defend the north if needed. Lastly, it should not allocate limited DOD assets to the region because high-priority theaters like Indo-Pacific, Europe, and the Middle East are already under-resourced. These measures can effectively manage Arctic interests within the appropriate context of focused national strategy.

Endnotes

1. Frank G. Hoffman, “Strategy as an Appetite Suppressant,” War on the Rocks, March 3, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/03/strategy-as-appetite-suppressant/.

2. U.S. Department of Defense, “2024 Arctic Strategy,” https://media.defense.gov/2024/Jul/22/2003507411/-1/-1/0/DOD-ARCTIC-STRATEGY-2024.PDF.

3. Donald J. Trump, “United States National Security Strategy, November 2025,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf.

4. “Arctic Shipping Update: 37% Increase in Ships in the Arctic Over 10 Years,” Arctic Council, January 31, 2024, https://arctic-council.org/news/increase-in-arctic-shipping/ and Malte Humpbert, “Chinese Containership ‘Istanbul Bridge’ Reaches UK via Arctic Route in Record 20 Days,” gCaptain, October 13, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/chinese-containership-istanbul-bridge-reaches-uk-via-arctic-route-in-record-20-days/?subscriber=true&goal=0_f50174ef03-5ee6139183-381157581&mc_cid=5ee6139183&mc_eid=64e8ec0a99.

5. “Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, Updated July 2, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R41153.

6. Cornell Overfield, “Wrangling Warships: Russia’s Proposed Law on Northern Sea Route Navigation,” Lawfare, October 17, 2022, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/wrangling-warships-russias-proposed-law-northern-sea-route-navigation.

7. ”Main Results of NSR Transit Navigation in 2024,” Centre for High North Logistics, NORD University, November 28, 2024, https://chnl.no/news/main-results-of-nsr-transit-navigation-in-2024/.

8. Brendan Murray and Danielle Bochove, “China Turns to Arctic Shortcut While Major Carriers Steer Clear,” gCaptain, October 3, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/china-turns-to-arctic-shortcut-while-major-carriers-steer-clear/.

9. “International Voyages on the Northwest Passage in 2024,” Aker Arctic, November 13, 2024, https://akerarctic.fi/news/international-voyages-on-the-northwest-passage-in-2024/.

10. Stephen M. Carmel, “Taking a Round-Turn on Reality: Commercial Shipping through the Arctic,” email to author.

11. Malte Humpert, ”Chinese Companies Dispatch Multiple Container Ships Along Arctic Route for Faster European Trade,” High North News, August 4, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/chinese-companies-dispatch-multiple-container-ships-along-arctic-route-for-faster-europe-trade/.

12. ”Ship crossings through global maritime passage: January 2022 to April 2024,” Office of National Statistics, https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/internationaltrade/bulletins/shipcrossingsthroughglobalmaritimepassages/january2022toapril2024.

13. ”Sea Ice Chokes the Northwest Passage,” NASA Visible Earth, August 8, 2024, https://visibleearth.nasa.gov/images/153166/sea-ice-chokes-the-northwest-passage.

14. Malte Humpert, “Sanctioned Suezmax Oil Tanker Without Ice Protection Stuck for Days on Russia’s Arctic Northern Sea Route,” gCaptain, September 15, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/sanctioned-suezmax-oil-tanker-without-ice-protection-stuck-for-days-on-russias-arctic-northern-sea-route/?subscriber=true&goal=0_f50174ef03-245bcea0f7-381157581&mc_cid=245bcea0f7.

15. Malte Humpbert, ” Russia Pushes ‘Shadow Fleet’ to Limit as LNG Carrier Struggles Through Early Arctic Ice on Northern Sea Route,” gCaptain, November 3, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/russia-pushes-shadow-fleet-to-limit-as-lng-carrier-struggles-through-early-arctic-ice-on-northern-sea-route/.

16. Malte Humpbert, ”Two Salvage Vessels Arrive in Canadian Arctic to Begin Refloating of Grounded ‘Thamesborg’,” gCaptain, September 23, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/two-salvage-vessels-arrive-in-canadian-arctic-to-begin-refloating-of-grounded-thamesborg/?subscriber=true&goal=0_f50174ef03-a458a9f7c7-381157581&mc_cid=a458a9f7c7&mc_eid=64e8ec0a99.

17. Malte Humpbert, ” Arctic Cargo Ship ‘Thamesborg’ Refloated AIS Data Show, Awaiting Company Confirmation,” gCaptain, October 9, 2025, https://gcaptain.com/arctic-cargo-ship-thamesborg-refloated-ais-data-show-awaiting-company-confirmation/?subscriber=true&goal=0_f50174ef03-400f2f7a4e-381157581&mc_cid=400f2f7a4e&mc_eid=64e8ec0a99.

18. Stew Magnusen, ” The Icebreaker Numbers Game,” National Defense, January 13, 2025, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2025/1/13/the-icebreaker-numbers-game.

19. ”DHS Celebrates Purchase of New Coast Guard Icebreakers as President Trump Signs Deal with Finland,” Department of Homeland Security, October 10, 2025, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2025/10/10/dhs-celebrates-purchase-new-coast-guard-icebreakers-president-trump-signs-deal.

20. Nouman Ali, “The Cost of Icebreaking Services,” SeaRates, Jun 11, 2020, https://www.searates.com/blog/post/the-cost-of-icebreaking-services.

21. Stephen M. Carmel, “Taking a Round-Turn on Reality: Commercial Shipping through the Arctic,” email to author.

22. Mark Rowe, ”Arctic nations are squaring up to exploit the region’s rich natural resources,” Geographical, August 12, 2022, https://geographical.co.uk/geopolitics/the-world-is-gearing-up-to-mine-the-arctic.

23. Mia Landauer, Niklas Swanström, and Michael E. Goodsite, ”Mineral Resources in the Arctic: Sino-Russian Cooperation and the Disruption of Western Supply Chains,” Niklas Swanström & Filip Borges Månsson, editors, The “New” Frontier: Sino-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic and its Geopolitical Implications, September 2025, Institute for Security and Development Policy, https://www.isdp.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/SP-Arctic-Sep-2025-final.pdf.

24. Ibid, p.109.

25. Mark Rowe, ”Arctic nations are squaring up to exploit the region’s rich natural resources,” Geographical, August 12, 2022, https://geographical.co.uk/geopolitics/the-world-is-gearing-up-to-mine-the-arctic.

26. ”Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Status of Oil and Gas Program,” Congressional Research Service, updated July 24, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12006#:~:text=On%20January%208%2C%202025%2C%20DOI,the%20lease%20sale%20discouraged%20participation.

27. Sune Engel Rasmussen, ” Inside the West’s Race to Defend the Arctic,” Wall Street Journal, October 11, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/world/inside-the-wests-race-to-defend-the-arctic-0f04ca7a?gaa_at=eafs&gaa_n=ASWzDAi4UrfELbN8TNIpkiANQ9qkJ409UcY7ybn1KHm71Es8FzKPdjCv2Sk3_6eJxEI%3D&gaa_ts=68efa5d0&gaa_sig=X9bLexZswY1r8pD8-BgF7-BUcPWUSkNZB5DFNXcqGswh-PVRHJkHIZ_O-GK6LEEDyK8b2uDpyvgFayIxLxTHnA%3D%3D.

28. Michael S. Brown, ”Rethinking the Arctic Threat Landscape,” Proceedings, November 2025, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/november/rethinking-arctic-threat-landscape?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=PWNov6-25&utm_id=PWNov625&utm_source=U.S.+Naval+Institute&utm_campaign=f01c9a3224-Proceedings_This_Week_2025_6_November&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_adee2c2162-f01c9a3224-223022301&mc_cid=f01c9a3224&mc_eid=e0ac270dd4.

Featured Image: The icebreaker USCGC Healy (WAGB 20) keeps station while conducting crane operations alongside a multi-year ice floe for a science evolution in the Beaufort Sea, Aug. 9, 2023. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Briana Carter)