By Tom Sharpe*

The march to autonomy in warfare continues. Led by Ukraine and closely followed by China, the obvious requirement for “lethal mass” demands it. Whilst the direction of travel is unambiguous, the rate at which countries are progressing down it varies depending on how innovative they are and, often, how much hard cash they spend. In the UK, we could lead on the former but are lagging on the latter.

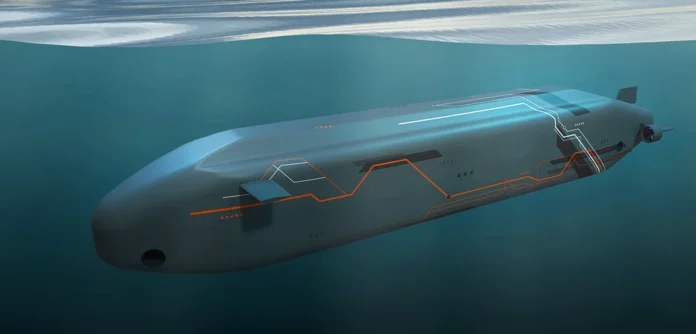

Nevertheless, one example emerging that has caught the eye is the Herne extra-large uncrewed underwater vehicle (XLUUV). Built in a collaboration between BAE and Cellula Robotics and “available to purchase from the end of 2026” this is an interesting development. There are a huge amount of variables when it comes to cost but as an indicator, you could buy over 50 of these for the price of a single Astute-class attack submarine. But should we do that?

First, I spent far too long at sea getting battered by the elements and having to fix stuff. For something even vaguely complex to work in the real world out there, not as a demonstrator, it will need to be extraordinarily well made. This will be expensive.

Third is processing power and data transfer. How good these are will determine if your UUV can be used as a weapon or ‘just’ a sensor. It will determine if it is a posh remotely operated vehicle or genuinely autonomous, decision-making force multiplier.

The UK military operates in a tight Rules of Engagement environment to ensure compliance with international law. Key decisions will still need to be made by humans, no matter how ‘clever’ your autonomous system is. You therefore need to find a way to get the data you have just gained to the decision maker and back again fast enough to be of use. In a normal submarine, this person is standing next to you. Here, you have to bend physics to make it work – communicating underwater is really, really hard. If your XLUUV gets round this by deploying a buoy so that it can transmit its contact data immediately, then both the data and the buoy itself can be detected and potentially jammed by an alert enemy.

Having said all that, there is an arrow in the direction of military autonomy that is as assured as the arrow of time itself. The question for Defence, the Navy and, in this case, in the anti-submarine (ASW) battle, therefore, is how fast should we progress down it. Go too slowly and you cede the advantage to your adversaries. Go too fast and you write off existing equipment before the tech replacement is fully mature, as we have done with our mine countermeasures capability.

In the case of XLUUVs, new and exciting options are appearing fast. It was the BAE variant that triggered this article, but MSubs are already on contract with the Royal Navy with their Cetus, now Excalibur, alternative. This is slightly smaller than the Herne, but both have a 40 foot shipping container as their home-of-choice. To date, the Navy has bought just one, as a capability and reliability test platform.

I won’t go down the SME rabbit hole here, but suffice it to say, the environment companies like MSubs nare being asked to survive in is about as unfriendly and unhelpful as it’s possible to be. The MOD and to an extent the Royal Navy are not configured to support them and having your start-up being gazumped by a Prime defence contractor will remain a risk until this changes. The new First Sea Lord is leaning in hard here which is excellent, but will come up against the MOD’s baked-in resistance to change sooner rather than later. But let’s say General Jenkins and the Navy’s Future Development manage this and release the funds to be able to seriously ramp-up production of XLUUVs en masse, then what are they actually for?

A manned attack submarine has five primary roles: anti submarine warfare (ASW), anti-surface warfare, land-attack strike, intelligence gathering and special forces insertion. With the exception of the last one, they can switch between them at a moment’s notice and do so without anyone knowing. Submarines are hard to find. Someone is always about to discover a bit of tech that will render the oceans transparent but this is a record as old as submarines and normally surfaces when governments need to spend cash on replacing them. Ignore it for now – every serious navy has submarines.

ASW is a networked effort involving intelligence operators, satellites, aircraft, ships and other submarines. The earlier you can detect, classify and track an adversary submarine, the sooner you can do something about it. Normally this involves tracking it discreetly to gather intelligence from it such as its acoustic signature, or letting it know you’ve detected it in order to deter it or chase it away. Exceptionally, you will need to destroy it. The obvious answer to “what are XLUUVs for” is to add mass to this network. A necklace of them across the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap would provide an excellent barrier to the Russian “out of area deployers” that routinely head this way. These Russian boats then prowl above our Critical Underwater Infrastructure, try to get on the trail of our deterrent submarines, or, as they did recently, attempt to close in on a US Navy aircraft carrier off Norway. It’s a real threat facing mainland UK everyday, not some future possibility, and we need to be able to deal with it.

To contribute, the ULUUVs will need range, endurance and reliability as mentioned before. Air independent versions are being developed that will satisfy this. They will need to be quiet themselves and given how they are powered, their size, and hydrodynamically simple hull form, it is safe to say they will be. Their sensors will need to be first class. This is an area that is developing quickly with lots of companies finding ways to put capable sonar arrays into small spaces. They could also trail an array out behind them and be equipped with other, non acoustic detection measures that our larger boats routinely trial. They will have a bay that could deploy other devices – drones from drones. Get really clever and those drones, or even the XLUUV, could simulate a much larger submarine to confuse the enemy’s own picture. All of this is being trialled today.

A key variable is who is doing the tactical decision making in all this. A manned submarine carries exhaustively trained decision making humans. Can the AI onboard replace this or will it need to be done ashore? In a normal intercept, the manned submarine will be cued onto the contact of interest, coming from a direction and depth that maximises the chance of detection and minimises the chance of counter detection. Once “in contact”, the target will need to be classified, target motion analysis conducted – i.e. finding out what is it doing and why – and decisions made on all this. If the AI brain is to do this, then the XLUUV will need a highly classified mission library installed (which you do not want washing up ashore somewhere) and some advanced processors (which will get through a lot of power).

If the thinking is to be done ashore then you immediately get into the communications issue outlined above. Can you get that data ashore undetected and pinged back to the submersible – or a different one equipped to act on the data – in time to be of use? Even in the slower world of underwater warfare, a “position course and speed” report only needs to be a few hours old for the “furthest on circles” to get so large as to be of little use. This is the interesting part and if you press tech companies for an answer on how to solve all this, you don’t really get one. This suggests to me that it’s because, at the moment, they don’t know the answer. The Navy bought the Excalibur precisely to look at all this, but there is much still to do. This is the reason why, for now, these drones will be used as sensors and not weapons.

Of the other roles, anti-surface warfare is easier and could be done by an XLUUV. They could certainly sit near a chokepoint, hover into tide and track and report vessels as they pass although there are other, better, ways of doing this. Their lack of fin would make operating optical or other masts a challenge. ‘Strike’ they could not do – the ones we are looking at are not big enough. Intelligence gathering or signals interception close to someone else’s ports or cities is an option although they would need the legs to get there and again, get that data back undetected. However, sometimes these missions are a slow burn and waiting a few weeks for the XLUUV to return with the intercept data still onboard would be acceptable. Special Forces could use them as part of a wider tool kit and if we to ever get back into mine-laying, then they could do that. There is certainly plenty they could do in the future as the capability matures.

The final note of caution with programs like this is that our Treasury won’t care about the nuances of ASW, sensors or lethality. They will just see a cheap per-unit option that doesn’t even need people in it. That you still need people, just somewhere else, will be ignored. I suggested recently that we should buy some diesel-electric submarines to rebuild operator experience for our beleaguered nuclear submarine fleet. This remains valid and in an ideal world, you would have a spread of nuclear, diesel and uncrewed boats. But we’re not in one of those and it would not be unprecedented for the Treasury to say, “you can’t have those because you have XLUUVs”.

Lots of countries are looking at this capability now. The US has its Orca programme and Australia the ambitious Ghost Shark program. The cynics and the cautious think this programme is overly ambitious as they intend to use it as a weapon as well as a sensor, but let’s see. China is building XLUUVs at a rate of knots with images of their newest ones clearly showing that they will be used to lay mines. Russia has been doing this sort of thing for decades through the secretive GUGI underwater covert ops directorate. Most of their systems tend towards remotely operated rather than autonomous but they will be transitioning to the latter just like everyone else.

We need to be very clear what our XLUUVs will be for and not overreach if we are to keep up in this interesting and rapidly advancing Defence frontier.

*Commander Tom Sharpe is a former Royal Navy officer with command experience on live operations against Russian submarines in the High North.

This article was first published in The Daily Telegraph (UK) and republished with the author’s permission.