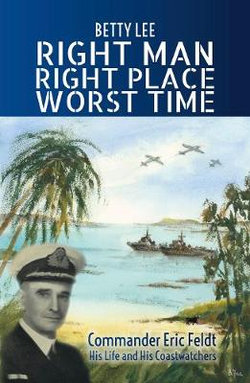

Right Man, Right Place, Worst Time. By Betty Lee. Booralong Press, Brisbane 2019.

Reviewed by Mark Edmonds

Right Man, Right Place, Worst Time is a biographical work about Commander Eric Feldt RAN OBE, written by a retired Medical doctor and member of the extended family.

Commander Feldt was the first wartime commander of the Coastwatchers, initially an organisation of civilians, then commissioned navy officers, spread out throughout the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA).

The Coastwatchers were formed in 1922 under the control of the Australian Naval Intelligence Division. By 1939, the organisation consisted of over 700 individuals across Australia, Papua New Guinea and the SWPA, and Lieutenant Commander Eric Feldt was appointed Supervising Intelligence Officer. Feldt began the process of equipping and training new Coastwatchers and developing procedures for the management of these individuals and the invaluable intelligence they produced, when the Japanese invasion began. Feldt himself remained in command until he suffered a heart attack in 1943, however the organisation he largely built continued to provide a critical role in the defence of Guadalcanal and maritime operations. He was subsequently awarded an OBE and went on to write the seminal work on the subject, “The Coastwatchers” (Feldt, E, 1946).

The author accessed a remarkable amount of primary material, including family journals dating back to the 19th century, oral history records and family correspondence. This provides a unique insight into the Feldt family’s migration to Australia from Sweden in the 1870s and life in the far north Queensland area where they lived. It is here Feldt was introduced to Islander culture, working alongside the Kanak labourers imported to harvest sugar cane. The resilience of these immigrants to Australia is astonishing and deserves greater scrutiny than it gets in the first chapter. Indeed, to the reviewer, this (and the last chapter) were the great revelations of this book – what life must have been like for Swedish emigres in Far North Queensland, not speaking the language, with few practical skills, but with a determination to make good in spite of considerable hardship. With this background, it should not be a surprise to us when we read later of Feldt’s civilian career in the colonial administration of New Guinea.

Feldt was accepted into the first class of the Royal Australian Naval College in 1913. His exploits and those of his peers are detailed in Vice Admiral Peter Jones RAN (Rtd) history on the subject. Feldt’s navy career did not last much longer than the war itself, and he soon found himself in the colonial administration in New Guinea. Until his recommissioning, he spent his career working and living in New Guinea and the Solomons, meeting the people (expatriate and locals) who would go on to become his most valuable allies and friends in the Coastwatchers. This extended network of relationships is detailed admirably in this book, again based on oral histories told by Feldt himself. This aspect of the work is fascinating, providing readers with insights into life in inter-war New Guinea as well as insights into how Feldt was able to succeed in his subsequent role as leader of the Coastwatchers.

The book then spends several chapters recounting stories of Coastwatchers during Feldt’s period of leadership, and it is here where perhaps some direction is lost. Feldt’s own history is exhaustive and whilst he represents his own role in a way characteristic of so many World War 2 veterans (that is, understated and with humility), the exploits of the individuals under his command is captured in considerable detail. What is missing, which might have added value to the reader’s understanding of the role of the Coastwatchers and Feldt’s leadership, is contextual information – war diaries, official histories, records of proceedings. One is left impressed by the heroics of the Coastwatchers, but generally unaware of Feldt’s work behind the scenes, and in managing the intelligence produced by these officers. This is not surprising given the dependence on Feldt’s own work – in his book he mentions himself only four times. The penultimate chapter concludes with Feldt’s heart attack and the cessation of his active role in the leadership of the Coastwatchers. Whilst we learn a little more about individuals, for the most part, we are left wondering what became of this organisation.

The last chapter returns the reader to the new and intriguing. It is a collection of vignettes about how the Coastwatchers faired in post war memorials, the media, social and pop culture, official recognition (Feldt spent many years on and off battling for an adequate pension) and of course the fate of individuals mentioned throughout the book. One learns of the many films which are nested in the Coastwatchers narrative. Feldt’s book was translated into French and the obligatory unit association sets about memorialising the work of the Coastwatchers in Australia and Papua New Guinea.

Overall, this is a fascinating read but one which leaves the reader a little unsatisfied. The family history and life in colonial New Guinea; and the post-war reflections on the role of the Coastwatchers in popular culture, are genuinely interesting. Whilst the valour of the individuals in the Coastwatchers is communicated clearly, there is little added from Feldt’s own work (which continues the narrative after his own medical impairment), and the role of the Coastwatchers in the larger naval intelligence and war effort is only dealt with superficially. Whilst there is a wealth of biographical and colloquial works on the Coastwatchers, the subject, by virtue of its importance, is crying out for an official “unit history” type work.