Sailor, scholar, teacher, friend: remembering James Goldrick a year on

By Sudarshan Shrikhande*

At a juncture in the lives of our two big countries, one a continent, and another a sub-continent; one the world’s most populous and one not quite; one straddling two oceans, the Pacific and the Indian, and the other sitting in the centre of an eponymous one, it may be appropriate to mark the robustly growing strategic proximity, mutual trust, trade, military to military and people to people contacts.

The oceans that imposed a tyranny of distance and a significant level of mutual indifference and even a degree of animosity between Australia and India that perhaps grew in the 1980s and peaked in the 1990s now draw us closer. Many factors have bridged the distance. Was the late RADM James Goldrick one such factor?

The Indian Connection

Imagine, therefore, a keen, young RAN officer, James Goldrick, astutely discovering naval connections between the RAN and the Indian Navy (IN). In 1984/85, as an Australian exchange officer in the RN’s fleet, he used to spend some of his free time trawling British archives instead of crawling across English pubs as some younger officers might have been expected to do. This happened while researching the post-war development of the RAN from a British Admiralty perspective. He then happened to start reading similar archives about the IN. In his own words, “Two themes were soon evident…The first was the similarity between the challenges and difficulties which the Indian Navy was facing with those of my own service and the similarity of the responses which were made by each navy. The second was the dichotomy between India’s strategic traditions and the assessment which the Indian naval staff developed and sustained of India’s naval requirements.” [1] In fact, the resultant paper from 1987, The Parted Garment… became a basis for his subsequent research that led to the publication of No Easy Answers: The Development of the Navies of India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka 1945-1996. That interestingly titled paper was excerpted in an early volume of the IN’s official history.[2] How about that?

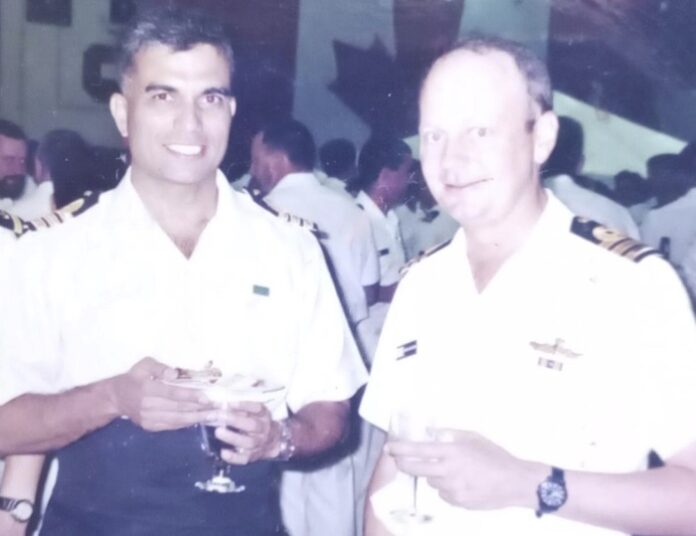

It was in the quest of learning more about the Indian Navy, that Commander James Goldrick spotted an IN commander—yours truly—in the hangar of USS Independence at a reception during RIMPAC-1996, nearly three decades back. I was there as one of two IN observers the IN had sent and he was XO of HMAS Perth. It was my Navy’s first-ever involvement in the RIMPAC series. We got talking and it struck me that I was speaking with an exceedingly knowledgeable, curious and perceptive seaman who was writing a book that was mainly on my Navy! Here is a memory of that day, (Attached photo May be merged by ANI editors) that has become so much more valuable for me because James crossed the bar so very early in life when he could have enriched so many so much more. I did read No Easy Answers two years after it was published in 1998 and was impressed with his understanding, analyses and the skill with which he could convey the essence of the difficulties different navies faced in contexts that were not necessarily similar. Yet, he could flesh out commonalities within the differences. He made two points in the Introduction which are worth noting in his own words:

First, “The ability of nations to organise and maintain naval services depended in the absence of external assistance, more directly upon the level of national development across a range of areas from elementary education to heavy industry than almost any other national activity. Much naval planning effort had therefore to be directed towards finding ways to overcome the deficiencies which were otherwise inevitable in a developing nation state.”

“A second repeated theme was the alienation which tended to develop between navies and the generally predominant national armies and between naval staffs and the remainder of the national strategic decision makers. The superficial cause of this phenomenon was the semi-dependent relationship on larger navies which either appeared to be the relic of colonial times or which grew up as small services were forced to look overseas for the assistance which their national economies could not provide.”[3]

“Helping the Navy Understand Itself”

Only someone with James’ erudition, precision and deep understanding of navies and seapower spanning centuries and relate it to the present and likely future contexts, could have said what he did say to VADM Peter Jones while the sun of his life itself was sinking into the horizon. Very aptly, he told Peter that perhaps his life’s contribution could be summed up as “Helping the Navy understand itself.” Lest any younger reader misunderstand, I feel this line reflects James’ modesty as well as his empathy, but above all his ability to make the history of his own Navy a palpable entity to those who served currently and quite likely for a long time to come via his books, papers and recorded lectures. James was surely the type of leader and naval intellectual who will continue to reach out to navy folks who will never get to meet him. He loved his Navy deeply, and served most professionally, while keeping a watch over it and writing with a critical eye. I am as privileged to know Peter, his term-mate, as I was to know James. As his ‘shipmate’ of nearly five decades, friend, collaborator and scholarly opposite number, Peter maintained station alongside James in the final, difficult weeks. He included this thoughtful summation of what James said in an email to me a few days before James slipped his mooring. In bringing these words in eulogies and elsewhere, Admiral Jones and Dr David Stevens have helped us understand the larger purpose to which James dedicated his life and did so undoubtedly from his youngest days. James perhaps sensed in me a sort of kindred spirit and thanks to him I came to know his term mates Peter and David and others including younger officers who he had mentored in his own, wise, smiling ways.

After 1996, I met him again in Mumbai towards the end of 2004, at a time when I was getting ready to move to Canberra as the Indian defence adviser at our High Commission. He had visited the Indian National Defence Academy, Pune on an exchange visit as Commandant of ADFA. Based on my predecessor’s heads-up from Canberra, we invited him to talk to the Naval Higher Command Course at the College of Naval Warfare (CNW), where I was teaching. He spoke about his experience as OTC of a coalition task force in the Perian Gulf. He was candid and shared several insights into his command experience. He could weave humour into the way he understood different operating cultures within a ship; working with a multi-national staff; differing levels of professional approaches and different attitudes to accepting and taking risks. It was clear that we had listened to a regular seaman officer, known within the IN, even if in small pockets for his understanding of our Navy. By the way, this was the first time that a foreign speaker had interacted with the CNW. That it was an RAN officer who was given the opportunity may have been more of a coincidence and a timely heads- up by our DA to his own designated reliever. However, what could be said that IN-RAN cooperation began to pick up speed and purpose around that time to the stage we see today.

Time Down Under

In spending a little over three years as the DA in Canberra until Feb 2008, apart from getting to understand the ADF, Australian defence challenges and participating in the task of improving the security and defence relationship between our countries, were opportunities for me to meet James more often, including when he headed the Border Protection Command after having been the Commandant of ADFA. He gave me access to the ADFA library and enabled more friendships to be formed. Our conversations were wide-ranging even when they were circumscribed by propriety and limited to the ‘UNCLAS’ world most understandably. In that matter, we always proper and discovered we could converse with a honesty that never crossed propriety, but was underlined by our individual affection for one’s own navy, one’s own professional life and to understand the other’s Navy. An amusing memory comes to me. James and I were talking about think tanks and he said, with the quiet smile and mischievous eyes that the “problem with some think tanks was that they were more into CBMs than in thinking and writing” serious stuff. Naturally, I knew there was a subtle joke (and a lesson) and asked him what did he expand CBMs into? “Conference Building Measures” was his answer! His association with many think tanks the world over and some in India was deep as well as wide where he valuably contributed with his dogged preparation, understanding of history, seamanship, and of command itself. Through his articles, lectures and discussions in conferences he educated others and absorbed a lot himself. James was a good listener!

We had several common interests and often similar views. One must say right away that the major difference was that his research, writing and early start in helping ‘himself understand navies better’ put him in a league in which I did not rank at all. Thanks to him, over the years I came to know others like Dr John Reeve, Dr Stuart Kaye, LCDR Desmond Woods, CDRE Peter Leavy and a few others as an informal, occasional ‘chat-group’ about navies in general and its people in particular. This included working on chapters for a book that is revisiting the work of Late RADM Richard Hill, Maritime Strategy for Middle Powers, in a contemporary context

As a DA I lectured at the ADFA and at RAN College, HMAS Creswell to help Aussie midshipmen and young officers ‘understand another country and another navy.’ (Readers may wish to access a fine article that Desmond Woods wrote on this and many other small ways in which the “P2P” relationship evolved between our navies.[4]) It happened, as I now largely feel due to James’ realisation and recorded by Admiral Jones for posterity in helping navies to understand each other.

“Advancing the Naval Profession”

In one of two very elegantly written chapters in the 2012 book, Dreadnought to Daring: 100 Years of Comment, Controversy and Debate in the Naval Review, James’ gravitas is obvious. [5] In fact, in much of his writing, James tried to look at the past with empathy, with an understanding that leaders and juniors of that period were working with the equipment they had, in the circumstances they encountered and in the command and control circumstances of their own time. He could also then relate it to contemporary circumstances. For instance, in Chapter 17, Life at Sea and Ship Organisation, he begins,

“…seeks to examine only efforts to treat these issues in a contemporary context; while there are many retrospectives within the NR, their value has been for historians rather than advancement of the naval profession. Our interest is in periods which the press of events has created a feeling that change is necessary and when the NR has identified that the contract between the nation and the people who man its Navy has become unbalanced.” [6]

Further in this chapter, is evidence of the thoroughness of his research through the archives of the NR; the care with which he could go into ship’s organisation and see continuities and disruptions in life at sea; of good and poor leadership; the strange idea that the Physical Training school propagated “that sports would provide the perfect bond between officers and men.” [7] I would think that only someone with James’ ability to get to the crux of problems that navies experience under different circumstances and often find solutions, related to his wide knowledge, sharp intellect and sense of history and the keen senses he developed for effectively leading others. For him seamanship, combat efficiency, engineering reliability, divisional systems, a wardroom’s professionalism and the mess decks’ morale all were parts of an important whole and parts of any navy’s history that could be related and examined alongside some other navy. I cannot but help recommending his chapters to those who are reading this article. One cannot also help but ask rhetorically, did James, even as a school boy and young officer write anything that may not have been worth a reader’s time? By his own admission, his great book, Before Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, August 1914- February 1915, had its genesis in 1971.[8] James must have barely on the threshold of teenage when he began reading the Naval Staff Monographs (Historical) that his naval father gave him. His first book, as the many tributes from last year pointed out, was The King’s Ships were at Sea: The War in the North Sea August 1914- February 1915 published over forty years ago. He must have been a most “Able” Lieutenant then at a time when I was a very ordinary Lieutenant. I could not read this book in its entirety because I ran out of time to do so. However, in reading Before Jutland (BJ) many years later, I could get a sense of how sharp his mind must have been then and how his experience, further research and even deeper appreciation reflected in BJ . Peter Jones and David Stevens were on the mark in their eulogy when they shared with the congregation that James was “Perhaps christened in saltwater… that one of the things he liked about the Navy was that if you were a ‘Nerd’ like him, provided you could be competent in seamanship, ship handling and leadership, then the Navy would accept you.”[9]

His 2016 interview with Christopher Nelson of CIMSEC.org is a fine way for those few in the RAN who may — and the many in other countries—who may not know of him, to get a sense of his wide-ranging wisdom and command of naval matters and seapower. [10] It combines his thoughts on naval history, historians, nuances of naval command, books and coal. Yes, even coal as the fuel that ships used, but where the quality of coal mattered a lot! On command and control, he drew parallels between the changes radio and wireless/telegraphy brought to WW I and how it impacted command as well as initiative which he conveyed thus:

We have got ourselves used to an uncontested electronic environment and a virtual reality which allows constant communication between commands and subordinates. That creates two problems: the one that gets talked about most frequently is the “thousand mile screwdriver.” But there is another problem that worries me even more and this is also a World War I problem – subordinates won’t make a decision; many would rather ask permission than seek forgiveness. And that I think creates the prospect that if communications are cut off, operations will be paralyzed because people will wait and see if communications become reestablished rather than do anything themselves. The direct parallel is the effect of radio on naval culture in 1914. Before radio, it was inherently bipolar. If you were in sight of the admiral, you were doing exactly what the admiral directed. But if you were not in sight of the admiral before radio, you knew what the intent was, and you went.

Down Under and Over Here

In my retirement since 2016, James and I kept up some correspondence by e-mail but met only a few times. Even his emails were so elegantly written combining sharp observations on issues of navies, jointery, seapower, the misunderstandings and misconceptions about fundamentals that ought to be first understood better by seamen, if they were to be understood by others. This we both attempted in parallel and together. For instance, we suggested that the term Non-traditional security threats was unhelpful for most threats under this rubric, but especially piracy. [11] There is also continuing confusion about say, sea control, sea denial and power projection because primarily navies tend to use these with more than required license. Together we wrote a short commentary, Sea denial is not enough: an Australian and Indian perspective.[12]

In his final years in service, James came across more Indian officers and delegations that studied/ visited Australia when he was once again closely involved with Professional Military Education (PME) as Commander of the Australian Defence College. A couple of things may be said here because I came across a few officers who had interacted with him due to my own involvement in PME in India. Firstly, they all came away impressed by his scholarship and the way in which he leveraged his own experience with that of others through centuries. Secondly, was the way in which he seems to have touched some in his small, inimitable ways. As we do know from things written about him, a young Goldrick had kept up correspondence with admirals and scholars as he went about his quest to learn and write. That included some in India. Something similar could be said about him reaching out to young officers to help them with their research. Let me mention just one case. Some years ago, at the Indian Staff College, a commander got in touch with me for a paper he was writing on the Battle of the Heligoland Bight. I thought it would be profitable for him to get in touch with James as well because of his scholarship on WW I. James readily agreed to my sharing his details. Cdr Puneet Bala knew James from being his liaison officer during a 2009 visit to India. After James’ passing, knowing of our friendship, he shared with me a letter he had got from James to thank him for his support during the visit. It is reproduced here. (May be included by editors.) It could be admired just for James’ calligraphy; neat, precise, and no rewriting! But, it could be admired even more for his thoughtfulness in doing so, personalising a message instead of leaving it to someone on the staff who would work on a template with minor variations for all one needed to mechanically thank. It could be said about James, what I had said of a much admired IN admiral on his passing a few years ago. “People interested him, and people were therefore, interested in him.”[13]

After Jutland and After Goldrick?

No doubt, his final major books, Before Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters August 1914- February 1915, (BJ) , and After Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, June 1916- November 1918,(AJ)were the apogee of his historical contribution to naval thought, which he continued to embellish with superb papers, articles and talks during his travels. Early in BJ, he analyses the vagaries of the RN’s varying cultures between big ships and smaller torpedo craft. “A senior officer’s authority was almost absolute and following the senior officer’s movements and routines were obligatory, while there was an unhealthy emphasis on choreographed close order maneuvering (sic)…creat(ing) a mindset of speedy response to direction rather than initiative in ambiguity.”[14] His concluding line of BJ is stunning in its simplicity; “If there is a lesson, it is that technology, organization, and culture matter and navies need to get all of them right.”[15]

The sequel, After Jutland (beautifully inscribed by James and presented to this writer in Canberra in Oct 2019) is also a retrospective on how navies learned, often at high cost, under the pressure of combat and how some perhaps fell short in some areas. It is written with a personal modesty that comes from knowledge, experience and an understanding how close to making errors one could be at sea, as he says, “There but for the grace of God, go I…”[16] The research on the Great War that James began way back in 1971and encountered in his chapters in Dreadnought to Daring, seems to have helped in the skilled reflections and comparisons he drew the British, the German as well as the Tsarist Navies. This ranged from battle doctrines, to victuals and mess organisations; from details of learning better command and control to failures of leveraging the fleet and forces at hand; from morale to mutinies. As the largest navy and of more consequence (at least potentially), the RN gets the more detailed examination including “problems…long ascribed to the Admiralty may have been as much the result of the inadequate organization of the operational commands as deficiencies in Whitehall.” AJ continued looking at the factors that he concluded BJ with. He inferred that technological developments of platforms and operational precepts between 1914 to 1918 were remarkable and some of these “foreshadowed the task forces of the next war” before concluding his book thus: “A modern observer can mourn lost opportunities in the Great War at sea, but it is only fair to recognize just how much was achieved as well.” [17]

Admiral Goldrick monitored, spoke and wrote concisely and incisively about the way the Quad, Malabar exercises, and Australia’s interactions with Asia were growing. The last time we spoke about these matters was over a lunch in Canberra we had in September 2022. It seemed that James was recovering well from his treatment and although he was not permitted to attend the eponymous Goldrick Seminar that year, I was immensely grateful that we had the chance to talk about just the matters that so interested both of us but in which his knowledge was so much deeper.

In one of the final e-mails we exchanged in February 2023 (James was not feeling well, once again) he was thinking about Australia and India’s post-colonial experience. It is very slightly edited here:

“I have just been pointing Professor….of the ADC to the Indian experience of civil-military relations and the parallels with our own, for much the same post-colonial reasons. Persuading the academics not to impose the template of Huntington is quite a challenge, even when one points out the fundamental difference between an administration appointed and senate confirmed US public servants and ours…. And then one has to explain that our post-colonial systems did not derive directly from the Westminster system and have never worked the same way (although I think Westminster has become more like us over the years).”

One can only agree with the thoughts of so many who recalled James’ contributions to naval and strategic thought from a fine mind of a sailor and scholar. His work will provide continued value to coming generations certainly in Australia, but also elsewhere. After all, how many twenty-one years old naval officers end up being authors and as Peter and David recounted are able to conclude a book with such a profound line: “History seems to repeat itself for only so long as its actors are unaware of what has gone before.”

Would it be wrong to say that he helped many navies understand themselves?

*Sudarshan “Shri” Shrikhande, RADM, IN (Ret)

[1]James Goldrick, No Easy Answers, The Development of the Navies of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, 1945-1996, New Delhi, Lancer Publishers:1997 from the Introduction, v

[2] Satyendra Sing, RADM (Ret), Blueprint to Bluewater: The Indian Navy: 1951-1965, New Delhi, Lancer Publications:1992. Copyright with IN. Goldrick’s paper was The Parted Garment: The Royal Navy and the Development of the Indian Navy 1945-1965.

[3] Goldrick, No Easy Answers, vii.

[4] Woods, Desmond, “Understanding Each Others’ Education and Training Methods: An “Aussie” reflection on IN-RAN Officer Exchange,” Indian Naval Despatch, https://indesfoundation.in/indes.php?id=9&page=2, 59-78.

[5] See Sudarshan Shrikhande in Book Review Essay, of the referred book, Dreadnought to Daring… published first in Maritime Affairs, National Maritime Summer 2013, and then by the British Naval Review in Vol 102, Number 1, February 2014, 75-83. The Essay was titled, A Fleet Under Review for a Century.

[6] Peter Hore (Ed), Dreadnought to Daring: 100 Years of Comment, Controversy and Debate in the Naval Review, Barnsley, Seaforth Publishing, 2012, 236.

[7] Ibid, 240. These observations relate to a period immediately after the Forst world War that makes it that much the stranger.

[8] In the Introduction to Before Jutland, 1-2.

[9] The author thanks VADM Peter Jones for kindly sharing this tribute via email after the Memorial Service on 05 April 2023.

[10] Interview with Christopher Nelson, “On Naval History, Books and Coal…” Cimsec.org, 15 February 2016, https://cimsec.org/naval-history-books-coal-interview-rear-admiral-james-goldrick-ranret/

[11] See, James Goldrick, “Let’s Stop Using the Term ‘Non-Traditional’ About Security Threats, “ The Strategist, ASPI, 24 June 2020, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/lets-stop-using-the-term-non-traditional-about-security-threats/, and Sudarshan Shrikhande,”Recognising and Leveraging the Traditionality of Non-Traditional Security Threats, in Synergy, Journal of the Centre for Joint Warfare Studies, Aug 2020, 180-194, https://cenjows.in/publications/synergy-aug-2020/.

[12] Goldrick & Shrikhande, “Sea denial is not enough: an Australian and Indian perspective,” Lowy, 10 March 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/sea-denial-not-enough-australian-indian-perspective.

[13] See Sudarshan Shrikhande, Obituary for VADM Manohar Awati written for bharatshakti.in, 05 November 2018, https://bharatshakti.in/manohar-awati-sailor-war-hero-adventurer-leader-chroniclercrosses-the-bar/

[14] Goldrick, BJ, 25.

[15] Ibid, 305.

[16] James Goldrick, After Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, June 1916- November 1918,Seaforth, Barnsley, 2018, 2.

[17] Goldrick, AJ, 283-284.