Introduction

NAVAL warfare officers spend the majority of their early careers at sea in the RAN either in single naval units or in modestly sized naval task groups. They are extensively trained in naval tactical planning on Principal Warfare Officer (PWO) course and use this training operationally at sea. However, the majority only get a rudimentary exposure to Joint planning or tactical planning in the land environment.

Yet given the methodical and logical way in which planning is addressed at the tactical and operational level in the land environment it is proposed that the RAN is disadvantaged by not embracing a similar planning methodology.

The RAN currently has no tactical planning methodology of its own, and until 2007 nor did the RN. In the last decade there was a shift towards a more doctrinal approach to planning in the RN, with the arrival of the Seven Question Maritime Tactical Estimate (MTE); a planning methodology developed from the combat or tactical estimate used for years by the British Army. Although formalised as doctrine, the MTE was neither intuitively, nor enthusiastically embraced by junior naval officers. Many felt that it was an infantry officer’s tool that had been imposed upon the RN by a land-centric establishment fighting two wars in the Middle East.

This article will attempt to demonstrate that a logical and critical thinking method of approaching a situation or problem is vital when embarking on a planning process. It will aim at first defining what planning is, before elaborating on the Military Appreciation Process (MAP); the Australian Army equivalent of the tactical estimate. Next it will address why the concepts behind MAP and similar methodologies are critical for planning, particularly in the ever greater complexity of the 21st Century. The article will then attempt to explain how the RAN currently plans and why, before looking at the development of British Military Doctrine as a comparison to the RAN and to determine why the adoption of the MTE by the RN early in the 21st Century. It will conclude by framing the importance of a logical planning methodology in the context of a complex modern world and why the training and education our Officers in this method of planning is critical in creating a winning force at sea.

Planning

Nelson planned well. Lambert, in his essay , addresses how the true lessons from Trafalgar were actually lost to the RN after the battle. In his argument Lambert refers to Dupin, a French academic, who was tasked by his government to analyse the success of the British against the French and Spanish at the battle. Dupin uncovered how Nelson used a process of mission analysis to determine his tactical decision-making. Nelson abandoned the classical fighting instructions of the day; to keep the line at all cost, not because they were wrong, but because through his analysis of the enemy and his own forces this tactic was unnecessary against unskilled foes eager to avoid battle. In essence, he conducted planning using a model that would be recognised by the proponents of modern tactical planning models.

Mazourenko and Jobst discuss how it is axiomatic that planning is fundamental to military operations. They continue by quoting Australian Defence Force (ADF) Joint planning doctrine and state that ‘effective planning is the pre-requisite for the successful conduct of military operations. A good plan is not a succession of fixed steps rather a solid foundation to adaption to changing circumstances’. Davis describes how effective planning enables us to make tactical decisions. Furthermore this paper emphasises tactical decision-making as a subordinate element of the military command and control system in the tactical planning context. He draws attention to how tactical decision-making is a problem solving exercise, which involves a systemic approach that is based on effective analysis and is designed to enhance effective application of professional knowledge, logic and judgement. It is therefore both an art and a science, but it cannot be left to chance.

The Naval way

The RAN of course plans and owns significant layers of tactical doctrine by which it trains to fight, but this paper attempts to understand why it has not embraced planning to the same degree as the Army, or joined the RN with its own tactical planning method.

Junior Army officers and NCOs will be taught from a very early stage about mission analysis, commander’s intent, COA development and war-gaming. However, a mention of any of these terms to junior naval officers will normally result in blank stares. As an example a patrol boat was tasked recently to shadow a foreign fishing vessel suspected of fishing illegally within the Australian EEZ. The Commanding Officer asked his Executive Officer and Navigating Officer, junior lieutenants with BWCs, to come up with a plan for this task and they were provided with an aide memoir of the IMAP process to guide their planning efforts. Though intelligent and capable officers, both were at a loss to how to conduct the basic preliminary scoping and mission analysis of the task. This was understandable, as they had never been exposed to this method of planning before.

On questioning them they were both vaguely aware of MAP, but had never received instruction on it. The only planning instruction they had received was on the use the NATO standard of orders used to brief a plan. By failing to instruct RAN junior officers to plan sufficiently and in a logical and intelligent manner encourages the behaviour celebrated by Abraham Maslow whereby “if you only have a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail”.

Typically a naval warfare officer will be introduced to the lexicon of planning on the Joint Operations Planning Course during Principal Warfare Officer’s course as a mid seniority LEUT or junior LCDR. This course will introduce the students to the Joint Military Appreciation Process (JMAP) used by the ADF to plan at the operational level. In hierarchy of planning this process sits above the MAP and is used at the operational level by a Joint Headquarters, the output from the JMAP will directly impact on how the tactical commanders plan using MAP. For non-warfare officers this exposure may not take place until as late in their careers as Advanced Command and Staff Course.

As indicated in the vignette of the foreign fishing vessel, the junior naval officer in the RAN is taught the NATO sequence of orders as part of their initial officer training. Andrew St George in his book on leadership in the RN describes this as ‘an important tool that allows a team to be aware of the situation and what needs to be done and how the end will be achieved’. At the New Entry Officers Course, RAN officers under training are taught to brief a plan using the acronym SMEAC: situation, mission, execution, administration and command and control. Useful as this may be, this method does not educate a young officer how to plan or analyse a mission or task. It is merely a delivery mechanism, which does not consider mission analysis, intelligence preparation of the battle space or other such logical planning sequences. Moreover this simple method of planning has no correlation with the JMAP process.

As discussed at the start of the paper, the introduction of the MTE was met with some disdain by RN officers, who believed the model with its unfamiliar terminology was best suited to a Land or Amphibious environment. Sloan in a series of articles for the Naval Review provides evidence which may account for this initial reluctance. He explains how in the age of sail traditional rules were taught to all naval officers to be instinctive, these were: attainment of the weather gauge (giving freedom of manoeuvre to the commander), damaging the enemies’ spars (limiting the enemy’s freedom of manoeuvre), a raking attack (to cause maximum casualties) and attack by boarding (resulting in the capture of the ship).

Although these rules were created for fighting sailors in the age of sail, their legacy survives to this day. PWOs are taught to know instinctively how to maximise their weapons and sensors to find the golden moment over the adversary. If this is the modern interpretation of finding the weather gauge and a raking attack, then why would the PWO bother with a formalised planning methodology such as the MTE or MAP when all you need is expertise over the use of your weapons and sensors in order to defeat the enemy?

Planning Land style

The Australian Army, much like its allied counter parts instructs its officers at the initial officer entry level how to conduct the Military Appreciation Process (MAP). The SMAP (Staff) and the IMAP (individual) are integral components to all officers training and indeed practical knowledge of the IMAP forms the cornerstone to the cadets’ successful graduation from the Royal Military College, Duntroon. At a lower level is the CMAP (combat) is an abbreviated process conducted quickly when something changes during the execution of a plan. IMAP is generally conducted from the platoon commander level with little or no staff support, whereas the SMAP is carried out by a Brigade staff and is a very deliberate and controlled process.

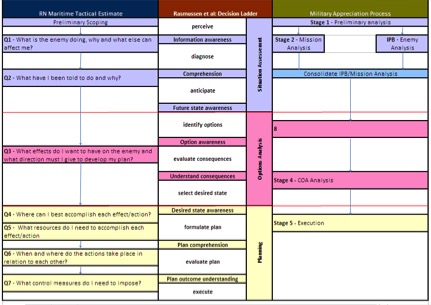

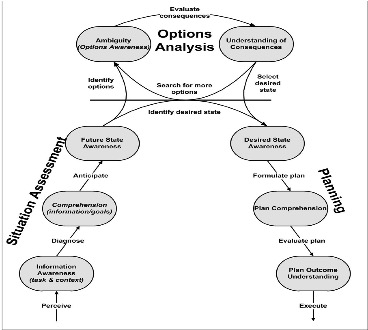

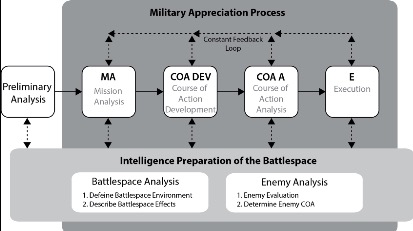

The MAP process can be simplified as follows: preliminary scoping; this stage provides the basis for the conduct of the planning task and sets the context for the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace (IPB). It should include the commander’s initial guidance and higher lever direction, an intelligence update, time constraints and planning considerations, force preparations and capability requirements.

Next comes mission analysis; this section focuses planning within the boundaries of the superior commander’s intent. The result of which should be the production of the mission statement as a basis for subsequent planning and decision-making. The key output for this section includes a list of specified and implied tasks, determination of freedom of action, identification of critical facts and assumptions, identification of friendly forces centre of gravity and their own critical capabilities, risks and vulnerabilities. Concurrent to the mission analysis the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlespace will be conducted by the intelligence specialists. This process effectively mirrors the friendly mission analysis, but for the enemy forces. Its output will provide analysis on the enemy centre of gravity, and its most dangerous and most likely course of action. From this work there is a consolidation of the mission analysis work and the IPB, whereby the commander decides how to attack the enemy critical vulnerability and thereby produces and number of decisive events that must take place to target the enemy COG.

The next MAP step is Course of Action Development. Here the staff will develop a number of plans that can be achieved. The integration of the products of the MA and the IPB to sequence the decisive events along lines of operation to construct a critical path to defeat the enemy centre of gravity. Next follows Course of Action Analysis whereby the advantage and disadvantage of each course of action is identified. Different processes of war-gaming can be used to validate each COA for workability, strengths and weaknesses. Improved and viable COA are passed forward for the next phase. In the execution step the commander compares the viable COA and determine which one has the highest probability of success. The selected COA is then developed into a plan and then issued. This plan is then executed.

A story of Doctrine?

It is open to debate as to why the RAN does not have a planning methodology like MAP or the MTE. Yet, by looking at the development of British military doctrine from the end of the Cold War it is understandable why the RN inherited the MTE. Mäder’s thesis offers a comprehensive history of post Cold War British military. In it he describes how Britain’s pre-1989 Armed forces did not appreciate this central idea of doctrine. He states that traditionally, British officers did not care about intellectual debate, and felt a deep reluctance towards any formal writings. He goes on to state how in this culture innovation was left to coincidence, largely steered by what was already known or physically available.

The drive for doctrinal change was driven by the British Army. In the first half of the 1990s the idea of doctrine began to be embraced by the three individual services. Their conceptual debate in these years was shaped by the end of the Cold War which was dominated by a rise in the use of conventional forces and the requirement for the British Armed Forces to understand their role in the new world order. As Mäder argues, during the four and half decades of East-West rivalry, Britain’s military-strategic thinking had ossified under the imperatives of Alliance strategy and nuclear deterrence. In Britain’s Armed Forces there was no mil-strategic concept other than their contributions to NATO defence.

Mäder goes on to report that the last service to incorporate the new understanding of doctrine was the Royal Navy. Its organisational culture was particularly hostile towards formal writings on the Service’s role, and only the impending development of a joint doctrine convinced the Service’s leadership to formulate its own doctrinal statement. He continues by stating that the Royal Navy’s culture was dominated by wide spread aversion against written doctrine. Procedure manuals and tactical level doctrine for naval warfare had always existed in great variety, yet higher-level doctrine was a different matter. Senior officers believed that prescriptive doctrine could endanger flexibility and freedom of action, two principles held high in the maritime environment and embedded in the Navy’s decentralised command and control philosophy.

But how does this development of doctrine link to the adoption of a tactical planning methodology? In the vanguard the British Army embraced two particularly important approaches which ended up heavily influencing the other services doctrinal development and ultimately joint doctrine. And it was this push to Jointery that ultimately had the impact at the tactic level for the Navy.

Manoeuvre Warfare and Mission Command

In the book, Race to the Swift , author Richard Simpkins presented the concept of manoeuvre theory and marked the starting moment of the British debate over manoeuvre warfare. As support gathered, the view emerged that the most promising way to military victory was to shatter the enemy’s overall cohesion and will to fight rather than destroy his men and material. Strength should be applied to areas of particular enemy weakness, his strategic or operational ‘Achilles heel’. Momentum, tempo, shock and surprise were the key features to this approach.

It is important to point out that the manoeuvrist approach was more than just physically out-manoeuvring an enemy. Mäder defines it from the doctrine as an approach to operations in which shattering the enemy’s overall cohesion and will to fight is paramount. It calls for an attitude of mind in which doing the unexpected, using initiative and seeking originality is combined with ruthless determination to succeed.

Interestingly, from the RN’s point of view, maritime power was inherently manoeuvrist. Historically and from the standpoint of modern doctrine, a navy does not have a choice between manoeuvre and other styles of warfare. Manoeuvre warfare theory is the intelligent use of force and is a logical development of the ‘principles of war’, particularly the principles of surprise, flexibility, concentration of force and economy of effort. Maritime forces have the combination of mobility, firepower, flexibility and responsive command and control systems that is ideal for manoeuvre warfare. It may be considered more an attitude of mind than an operational blueprint.

Andrew Gordon contributes to the debate by highlighting the difference between Military and Naval operations. He describes how in a typical land campaign much detailed knowledge would be known of the terrain and enemy dispositions and probable response options. As such highly scripted and time tabled orders would be both possible and necessary. Friendly artillery, air support and logistics all had to know where advancing units would be at given times. This was however largely untrue of operations at sea. Where in a free manoeuvre area, the time, place and nature of the next engagement with the enemy could not be scripted and therefore the naval commander had to largely innovate in the theme of the higher commander’s intent.

Adding to the picture, Hughes describes how a naval force can move at up to 500 nm in a day, whereas an army is pleased if it manages to move 25 miles per day (an average which has not changed since King Harold’s march from York to Hastings in 1066). Hughes goes on to explain how operations at sea can seamlessly transition between strategy, operations (which he calls operational logistics) and tactics. His point is that a Navy is largely self-sufficient, as a package it will move itself over great distances and be ready to deliver a range of strategic options to the government without significant reconfiguration. However, with the onwards push for developing a coordinated approach to doctrine the manoeuvrist approach was entered into RN doctrine.

The second approach championed by the Army was mission command. Mäder again describes this as the focus on achieving the right balance between delegation and control. The doctrine stated four enduring tenets to achieve mission command: timely decision making; a clear understanding of the superior commander’s intention; an ability on the part of subordinates to meet the superior commander’s remit; and the commander’s determination to see the plan through to a successful conclusion.

Going Purple

It was the push for more Jointery in the British Services that drove the RN towards a planning model taken from the Army estimate. Mäder describes how the theme of Joint development came to fruition in 1994 after a series of studies was conducted by the MoD focussing on the question on how to enhance Jointery. These studies resulted in the proposal of three major tri-service initiatives: the establishment of a Permanent Joint Headquarters, the creation of a Joint Rapid Deployment Force and the fusion of the existing single service staff colleges into a new Joint Services Command and Staff College.

In the question of planning, it is the formation of the Joint Staff College that is most germane. The main purpose of the JSCSC was to train officers from all three services in the planning and conduct of joint and combined operations. A united command and staff training was to enable the three services to achieve a common standard in the planning and conducting of operations. This Joint level of education quite obviously had a trickledown effect to all three services. But for the RN and its approach to tactical planning this was the genesis. The infusion of mission command and manoeuvre warfare in its doctrine, exposure to the Army centric Joint Staff Course set in the context of two serious land campaigns from 2003 onwards heralded the arrival of the army style of tactical planning to the RN with the adoption of the MTE in 2007.

Why this approach?

MAP is comparable to the RN MTE, which likewise is very similar to US and NATO armed forces planning methodologies. All these models follow a logic based decision processes; a reductionist method where by the problem is broken down for deduction (IPB and MA) and analysis (COA analysis and development) . The appeal of following a relatively simple step by step process is that it can be scaled for use from a small tactical unit to a larger task group staff.

The author of a Chief of Defence Force fellowship paper on critical thinking for defence planning, Dr Mazourenko, states that the articulation of the ‘logic of thinking’ that underpins planning is explicit at every level; from the strategic to tactical. This increases transparency and traceability of logical links between actions and their consequences, first in the plan itself and then during the execution phase. Generally the clarity of reasoning behind decisions facilitates better understanding between stakeholders to the plan, be it done under MTE, IMAP or any other methodology.

All military planning methodologies encourage and demand critical thinking. Mazourenko et al describe critical thinking as a key aspect to the logical planning process and furthermore states that a planning methodology framework can be vital to ensuring its success. Hall and Citrenbaum as cited by Mazourenko et al describe critical thinking as ‘an intellectual process that examines assumptions, discern hidden values, evaluates evidence and assesses conclusions’. Thus by following a planning methodology such as MAP the planner is engaged in such a way as to examine every fact and assumption related to the mission or task at hand and in theory nothing should be missed. By structuring the method in doctrine, planners will be guided by the process. Therefore in the event of crisis or war the thorough use and training this mode of thinking and planning will become second nature.

Fundamentally, successful tactical planning will leverage forces in such a way as to maximise the tactical and operational effect of employed forces. Mazourenko et al contend that military planning processes often focus on identifying and expressing desired outcomes. This results in a hierarchy that flows from the national strategic aim to campaign objectives to decisive conditions and supporting effects. It is in this space where tactical planning plays its role in the bigger picture; why achievement of lower level outcomes will lead to higher level outcomes.

In linking the tactical level to planning, Kelly contends that the link between tactics and strategy is provided in the western style planning process by the application of military analysis. Doctrine demands that in determining his or her mission, a commander considers and follows the intent of the commander ‘two-up’. This therefore links the lowest level tactical actions with the highest strategic aspirations’. Fry adds a historical analogy of this process not working in his RUSI speech by pointing out failures in Iraq in 2003. Such failures occurred in the coalition in applying tactical doctrine to operational effect in pursuit of strategic goals. He states that at the heart of successful tactics is the concept of transition and the ability to switch between operations of war.

The requirement for better military planning is not going to diminish. In the prize-winning essay , Lieutenant Commander Pitcher builds his thesis for future conflict around the persuasive ‘Hybrid war’ argument of Frank Hoffman ‘that blend[s] the lethality of state conflict with the fanatical and protracted fervour of irregular warfare’. Obviously it is inordinately difficult to predict the exact nature of warfare in the future, but the ‘hybrid war’ model seems as valid as many other schools of thought. This not so distant future features the increasingly likely scenario of state on state conflict, superimposed onto a world influenced by international non-state actors. All this will be set within the globalised system where the competition for resources and the devastating effects of natural disasters will be played out in increasingly populated littoral areas.

The sliding scale of future conflict and interaction will be conducted amongst people; reported on not only by the ubiquitous media but also before the citizen journalists armed with smart phones and instant connectivity to the internet. This ‘war amongst the people’ as coined by Rupert Smith will not be limited to just land forces. Emphasis on soft power versus hard power will be the key to mission success. In a recent book , two British military officers, Andrew Mackay and Steve Tatham, analyse recent conflicts in which they have both been personally involved over the previous 30 years, with particular focus on Iraq and Afghanistan. They come to the conclusion that the common weakness of all western militaries has been the inability to identify the character and nature of the opponent. Thus they are unable to exert the soft power of influence with any great effect.

Conclusion – why we must adapt the way we plan

Given the complexity of the modern world and the key role in which the modern naval officer plays within the maritime terrain now is the time to base our planning methodology on a more robust and logical framework. A framework that encourages our naval officers to think critically thinking, apply logic and explore all assumptions in a methodical planning process. Where decisions are made and can be tracked to the higher commander’s intent and part in the mission. Why shouldn’t the naval officer be trained to apply the language of intelligence planning of the battle space, mission analysis, decisive effect, centre of gravity and most likely course of action?

Even if this methodology is not fully embraced at the junior level, there is benefit in educating and training officers in this language now. Embracing tactical planning at the earliest stages of professional military education will create a ‘Trojan Horse’ effect; officers who will one day operate at the Joint level will find discover that their planning language is the Lingua Franca of operations. As senior officers they will be able to represent the Navy on a level playing field and perhaps lead the way in planning and conducting operations at the Joint or Combined level.

-o-o-O-o-o-

*LCDR Edmondson RAN served in the RN for 15 years as a warfare officer, holding various appointments at sea as a Navigator and PWO. He transferred to the RAN in 2011, serving in HMAS Newcastle as TASO, PWO instructor at HMAS Watson and most recently in command of Ardent Two patrol boat crew.