By David Hunt*

On 25 January, archaeologists announced that the body of Matthew Flinders, who had completed the first circumnavigation of Australia in 1803, had been found under London’s Euston station.

The discovery excited Australian interest more than it perhaps otherwise would. Three days earlier, Prime Minister Scott Morrison had announced the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook’s Endeavour voyage to Australia would be marked by a replica Endeavour circumnavigating the continent to “help Australians better understand Captain Cook’s historic voyage and its legacy for exploration, science and reconciliation”.

Australia has more statues of Matthew Flinders than of any other man – and more statues of his cat, Trim, than of any other cat.

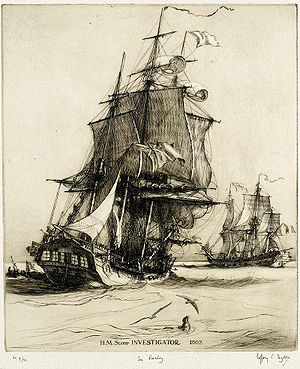

Culture warriors shriek-tweeted that sailing up an east coast, as Cook did in 1770, does not a circumnavigation make. Flinders, with his full Aussie 360 aboard the HMS Investigator, was a far worthier sailing-around-things pin-up – and he also had far more cred on the reconciliation front.

Cook’s first steps on Australian soil were marked by firing on two Gweagal men, and his last by claiming half of the uncircumnavigated maybe-continent for Great Britain – notwithstanding the Admiralty’s orders that any territorial claims should be made “with the consent of the natives”.

Flinders, in contrast, befriended Bennelong, the first Aboriginal man to visit England. He defused a confrontation in the Illawarra by giving the locals free haircuts and insisted that Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, join the Investigator to foster “a friendly intercourse with the inhabitants of other parts of the coast”.

Australia has more statues of Matthew Flinders than of any other man – and more statues of his cat, Trim, than of any other cat. Flinders named 348 places in Australia, compared with Cook’s 103, and in 1804 was the first person to call Australia Australia, so that we can still call it home.

The great man discovered Bass Strait, establishing that Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) was an island and dramatically cutting the sailing time from Britain to Sydney. His 1802-1803 circumnavigation proved Australia was both the world’s smallest continent and the world’s largest island, which is a pretty impressive double act.

Flinders pioneered the use of ship cannons to make speed of sound calculations to determine the position of places on land. He solved the problem of magnetic deviation at sea, allowing accurate navigation under cloud cover. He was the first person in the world to use a marine barometer to predict changes in wind velocity and direction.

When it comes to Australian exploration, science, and reconciliation, Matthew Flinders is your go-to guy.

Flinders’ life also highlights the manner in which France and Great Britain integrated science and foreign policy to make territorial claims, maintain diplomatic channels, and engage in espionage.

The Investigator continued the voyage of scientific discovery tradition pioneered by Louis-Antoine de Bouganville in 1766-1769, carrying a cross-disciplinary team of boffins handpicked by Sir Joseph Banks.

Banks, Cook’s botanist on Britain’s first scientific voyage, had been elected president of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest national scientific institution, in 1778. He held the post until his death in 1820, working with the Admiralty in arranging scientific voyages during his tenure. He harnessed Britain’s scientists to support the nation’s colonial and trade agendas and advised the Crown on colonisation, exploration, agriculture, currency, and other matters.

Britain’s scientific voyages also had colonial aims. Cook, for example, had secret orders (so as not to tip off the French) to search for Terra Australis during the Endeavour voyage and take possession of its “convenient situations”.

Britain enforced its claim in 1788, when it followed Banks’ advice to establish a convict colony in New South Wales. The colony was also founded for strategic reasons: to source shipbuilding supplies for the Royal Navy, to provide a base for Pacific trade, and to deter the French from establishing South Pacific colonies.

Louis Saint-Aloüarn and Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne had claimed western Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand for Louis XV in 1772, although France never took action to settle and establish sovereignty in those areas.

Flinders’ circumnavigation proposal was championed by Banks, as France had commissioned Nicolas Baudin to comprehensively chart the region and investigate its people, plants, animals, and minerals.

France and Britain were at war when the Investigator set sail in 1801. Yet Banks had arranged a British passport for Baudin, with the French doing likewise for Flinders.

France had ordered protection and assistance for Cook during the American War of Independence and for George Vancouver, who claimed western Australia for Britain in 1791, during the French Revolutionary Wars. Britain also didn’t interfere with French scientific expeditions.

Banks continued as a member of the Institut de France during the numerous Anglo-French wars during his presidency, with the Royal Society and Institut providing diplomatic backchannels during hostilities.

Flinders and his cat beat Baudin and his monkey in the race around Australia, with the two expeditions meeting in South Australia’s Encounter Bay. Flinders and Baudin compared their charts and discussed their discoveries, before Baudin’s crew, riddled with scurvy, limped into Sydney.

Baudin’s men were nursed back to health, with two of his party, Louis de Freycinet and the naturalist, François Péron, rising from their sickbeds to prepare reports on how the French might invade Sydney.

Baudin’s naming southern Australia Terre Napoleon and some comments over drinks about Van Diemen’s Land, convinced Governor King that Baudin planned to claim the southern island. He ordered Charles Robbins to follow Baudin in the Cumberland, with Robbins attempting to gazump Baudin by claiming Van Diemen’s Land for Britain on King Island. Such was Robbin’s haste, that he hung the British flag upside down and had to borrow gunpowder from Baudin for the accompanying military salute. Baudin was incensed, advising he had “no intention of annexing a country already inhabited by savages”.

Flinders, sailing for Britain aboard the Cumberland after his circumnavigation, was forced to stop at the French colony of Île de France (Mauritius). Péron, who’d left the island the day before Flinders docked, had advised Governor Decaen that “we should destroy [Sydney] as soon as possible”.

Decaen placed Flinders under château arrest on suspicion of being a British spy, claiming that the French passport was only valid while Flinders was aboard the Investigator. Decaen later wrote that he would have promptly released Flinders, had the British officer not so rudely refused a dinner invitation from Madame Decaen.

Banks and the Institut de France lobbied Napoleon to release the unwilling diner. Decaen, directed to free Flinders as a good will gesture, replied he would show good will when the Royal Navy was no longer a threat to his colony and Flinders could no longer provide it with information on his defences.

Flinders was imprisoned for six-and-a-half years, with Trim believed to have been eaten by Mauritians, and the French publishing his ground-breaking charts of the Australian coast, during this period.

An era of scientific cooperation, where learned organisations provided effective diplomatic protections and backchannels during war, had been ended by a minor breach of dinner etiquette.

History often hangs on such small threads.

*David Hunt is the author of Girt: The Unauthorised History of Australia, winner of the 2014 Indie Award for Non-Fiction Book of the Year. The sequel, True Girt, was shortlisted for Audiobook of the Year at the 2017 Australian Book Industry Awards and for the 2017 Russell Prize for Humour Writing.

Republished with permission of the Lowy Institute