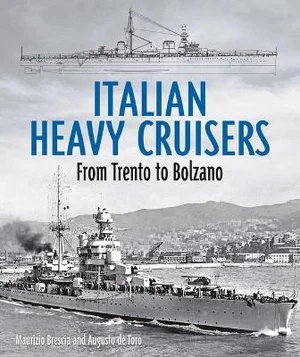

Italian Heavy Cruisers From Trento to Bolzano. By Maurizio Brescia and Augusto de Toro. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, 2022.

Reviewed by John Mortimer

This book is one of a series by Seaforth Publishing on Italian Navy warships from the Second World War. The other volumes are: “The Littorio Class Italy’s Last and Largest Battleships 1937-1948” by Erminio Bagnasco and Augusto De Toro; and “Italian Battleships Conte di Cavour and Duilio Classes 1911-1956” by Erminio Bagnasco and Augusto De Toro.

The structure of the book is logical and commences with a discussion of Italian Naval Policy and the 10,000 Ton Cruiser. This is followed by a Technical Description of the ships, Weapons and Fire Control, Aviation Facilities, Camouflage, Pre-War Activity of Italian Heavy Cruisers (1929-1940), Wartime Careers (June 1940-May 1945), and a final chapter on Conclusions and Comparisons with other heavy cruisers. Several appendix discuss Damage and Losses During the War, Full Speed and Range Trials, Night Gunfire and other issues.

In the aftermath of the First World War the General Staff of the Marine Nationale had set as priorities for the naval program and construction;

- Priority One – torpedo boats and submarines,

- Priority Two – scouts of light cruisers, and

- Priority Three – large ships.

These priorities had been driven by the naval experience of the First World War, especially the challenges of escorting shipping in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Washington Naval Disarmament Treaty of 1922 ( Great Britain, USA, France, Italy and Japan) restricted, inter-alia, signatory nations for warships, other than a capital ship or aircraft carrier to no larger than 10,000 tons (10,160 metric tons) standard displacement, and with guns no larger than 8 inches (203 millimetres).

Subsequent to the Washington Treaty Italy provided for construction of two heavy cruisers Trento and Trieste, in the 1923 Naval Program. In the following years there was debate within Navy on whether priority should be accorded to further heavy cruisers or small light cruisers armed with 6 inch guns. In the end the heavy cruiser argument prevailed. With the scrapping of battleships there remained a need for ships that had both defensive and offensive qualities required to carry out those missions of a strategic and tactical nature, that are not suitable for smaller vessels. Five further ships were subsequently built – Gorizia, Zara, Fiume, Pola and Bolzano.

On 30 April 1930 Italy announced its construction program for 1930/1931 which included the last heavy cruiser Pola and two 7,000 ton 6 inch gunned cruisers, which subsequently emerged as the Raimondo Montecuccoli class. Thereafter Italy concentrated on smaller cruisers.

All the heavy cruisers were in theory designed and built within the Washington Treaty constraints. The main focus of the design of Italy’s heavy cruisers was driven by the perceived threat from its neighbour France.

Other aspects of Italian naval policy are explored, including proposals relating to battleships and other warship types, broader naval treaty negotiations and, relevant naval developments in the five Washington Treaty navies.

The technical description of Italy’s heavy cruisers is extensive and includes excellent photographic coverage, ship plans covering the full ship as fitted and cross section plans, engine room plans, etc. There is also discussion of the ships hull and superstructure, building data, protection, steering gear, ground tackle, machinery, and auxiliary services,

Weapons and fire control are described in considerable detail and include the main and secondary armaments including 203mm guns, 100/47 guns, model 1932 37/54 machine guns, illumination howitzers, smaller machine guns and small calibre weapons, torpedo tubes, ammunition and magazines, and fire control. Variations in armament between the ships and upgrades are described and the text is complemented with drawings and photographs of the weapons.

During 1928 and 1929 aviation trials were undertaken aboard the cruiser Ancona, with the aircraft stowed and launched on the forecastle. This installation was implemented in the first two heavy cruisers, Trento and Trieste, as well as several of the new light cruisers. The aircraft were housed in a hangar below the forecastle and hoisted onto the catapult via a collapsible kingpost. This position in front of the forward 203mm gun mounting proved unsuitable for a number of reasons. It interfered with the arc of fire of the forward main armament and exposed the aircraft to the effects of blast, salt corrosion, as well as damage from heavy seas. Alternate arrangements right aft were trailed with two light cruisers (Diaz and Cardona) and were followed with a catapult between the funnels, which was decided as the most suitable site for aircraft launch and recovery. This arrangement was finally installed in Bolzano.

Aircraft trials and use of various floatplane types is discussed as are catapults and aircraft stowage arrangements. Photographs and drawings complement the text. These include a photo dated 4 January 1935, showing a ‘La Cierva’ autogyro on a wooden flight deck temporarily fitted on Fiume’s quarterdeck.

The chapter on camouflage discusses pre war paint schemes as well as wartime camouflage schemes. As expected the majority of the chapter comprises photographs, some of which are in colour, and drawings showing various camouflage patterns and when they were used.

Discussion of the ships operations in peace and war, as well as the Appendix on damage and losses during the Second World War provides a good feel for the role of navies in these different situations. Peacetime operations include:

- Trento’s cruise to South American countries in 1929 showing the flag, calling at Cape Verde Islands, Rio de Janeiro, Santos, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Ilha Grande, Bahia, the Canary Islands and Tangier.

- The deployment of Trento and the destroyer Espero in 1932 to strengthen the Italian presence at Shanghai subsequent to Sino-Japanese incidents at that city.

- Deployment of a force comprising Fiume and a squadron of destroyers to the Adriatic to exert influence during the Albanian Crises.

- During the Spanish Civil War the Navy was employed to support the Nationalists indirectly and directly, to rescue Italian citizens and other nationalities and to protect selected merchant shipping.

Wartime operations are covered in the previous books on battleships, except where the heavy cruisers were the main protagonists. This includes the Battle of Punta Stilo, the air raid on Taranto, counters to Operation Collar and the Battle of Cape Teulada, Operation Gaudo, the Battle of Cape Matapan, destruction of the Duisburg convoy, Alfa and ‘C’ convoys, Operation M42, the First and Second Battle of Sirte, countering the Britsh Operation MG1, the Battle of Mezzo Giugno, the Battle of Mezzo-Agosto, and the end of the 3rd Division at La Maddalena. Besides describing the actions, there are tables sometimes included comparing ammunition expenditure, British gunnery at Matapan and casualties on Italian ships. Appendix A, Damage and Losses during the Second World War, provides further information on the operations of the heavy cruisers. In particular, it provides specific details of the actual damage inflicted on the heavy cruisers and its impact on their fighting ability.

The final chapter provides an assessment of the heavy cruisers comparing the technical characteristics of the three main variants in Italian service, Trento and Trieste, Bolzano and the Zara class. This comparison reveals a steady growth in ship displacement; a reduction in speed; an increase in armament; an increase in weapons; a reduction in aircraft carrying capacity; and an increase in armour protection, electrical power and crew size.

There is also a comparison with other first and second generation heavy cruisers. The Italian Trento class, French Tourville and British Kent class from the first generation and the Zaras class, French Algerie and German Admiral Hipper class from the second generation. The authors conclude:

” …. the ‘10,000-ton cruisers were the most ‘political ‘ of the ships that emerged in the age of treaties, and one with the most uncertain role …. the Zara class, even with the limitations highlighted several times, can ideally be considered the most balanced and successful of the European 10,000 tonners; ….it was probably the Kent class that proved to be the most flexible and provided the most convincing results during conflict.”

This is an excellent book. It combines political, strategic, and financial considerations with the practicality of specifying, designing and operating ships which can contribute to naval operations both in peacetime and various levels of conflict. Many nations rushed to develop cruisers at the top end of displacement and main armament to complement the battleship and aircraft carrier in offensive operations. This notion soon gave way in many navies to the realisation that such ships could not be funded in the numbers needed to meet all naval requirements. Hence there was a realisation that more emphasis was needed to be directed towards the number of cruisers to meet national requirements. This stimulated the development of light cruiser designs, armed with 155mm (6 inch) guns.

The technical details in this book are extensive and provide good coverage of the issues involved in bringing into service major new capabilities, and the adoption of new technology. The problems encountered by all navies in this period is evident, and these challenges remain today. The Royal Australian Navy’s planned introduction of new nuclear powered attack submarines of United States and British origin, and the combination of a British frigate design with a US combat system and weapons will need to address and meet these challenges.