By Jennifer Parker*

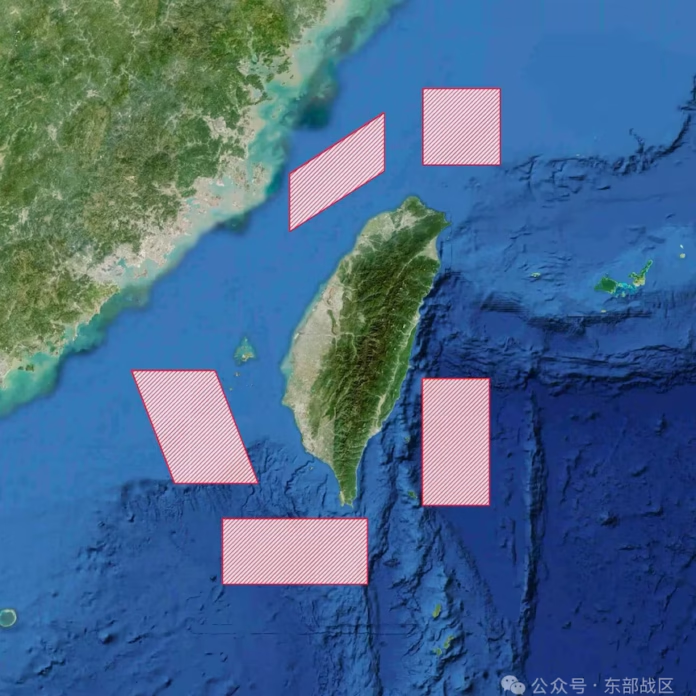

It is not even the end of January, yet 2026 is already marking a decisive break in the global order, and in Australia’s place within it. China ended 2025 with its largest military activity around Taiwan under Exercise Justice Mission. The United States has escalated pressure on Venezuela through a high-profile intervention, but it is the maritime pressure campaign behind it that should most concern Australia. And NATO unity is fraying as President Trump reintroduces coercive power politics, including threats against Greenland.

As Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney put it bluntly at Davos this week: “We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition.” Australia can no longer afford to treat this moment as abstract. The implications for our security are immediate.

Instinctively, Australia is a country that prefers to look inward, But that instinct is dangerous. Australia must pay far closer attention to how the world is changing and what those changes mean for our security and prosperity. The international system is being reshaped by several forces, most notably renewed great-power competition. Too often this is reduced to a false binary choice between the United States and China. It is not, and never has been. That oversimplification has plagued Australian strategic thinking for too long. President Trump’s threats against Greenland, and what they reveal about the United States in 2026, do not lessen the risks posed by China’s military build-up or its increasingly assertive use of force in the region. Australia must confront both realities at once.

These realities are further complicated by Australia’s greatest strategic vulnerability: its dependence on maritime trade. Recent US interdictions of shadow-fleet tankers linked to Venezuela demonstrate how easily a trade-dependent nation can be economically coerced through targeted maritime disruption. Australia is systemically exposed. Nearly 99 per cent of Australia’s imports and exports move through the maritime domain.

So how should Australia respond? Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney offered a clear answer in a speech that is likely to be studied for years to come. “We know the old order is not coming back. We shouldn’t mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy, but we believe that from the fracture we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just. This is the task of the middle powers.” Australia is one such middle power, with significant regional and global standing. Yet we have underinvested in key elements of national power. Addressing that gap is now an urgent strategic priority.

Australia’s standing ensures it is routinely invited into key rooms. That access must be used more deliberately to build issue selective regional minilateral and multilateral partnerships. For too long, Australia has assumed diplomacy can be done on the cheap. It cannot. Diplomatic power will be central to navigating an uncertain world and strengthening the collective voice of middle powers. Although the Albanese Government has increased DFAT funding, Australia’s diplomatic heft has not been restored. Our foreign service remains thinner, more stretched, and less influential than it was in the 1990s, despite a far more complex and contested strategic environment.

Increasing Australia’s diplomatic heft is also essential to diversifying our external relationships and reducing systemic vulnerability. Australia has begun to do this with partners such as Japan and the Philippines, but this effort must go much further. Deeper and more sustained engagement is needed with India, South Korea, Indonesia and Europe. Diplomatic diversification must also be matched by a harder conversation at home about economic vulnerability. That includes a serious examination of industrial policy, but also Australia’s central Achilles heel: excessive trade dependence on China. A stable relationship with China remains critical, but the scale of Australia’s economic exposure is no longer prudent. Rebalancing will be difficult and gradual, but allowing such concentrated dependence to persist constitutes a clear strategic vulnerability.

Diversification must be matched by the deliberate building of domestic resilience, economically, technologically and, critically, institutionally. For too long Australia has taken the strength of its institutions for granted. As ASIO Director Mike Burgess repeatedly warned in 2025, Australia’s institutions face growing pressure from both foreign interference and domestic fracture. Building national resilience in a world defined by power politics also requires stronger military resilience. The United States remains Australia’s central security ally. That alliance has endured shifts in global order, policy disagreement and changes of leadership in Washington. Australia should not step away from it. But we have become overly dependent, not by choice, but through strategic complacency. Australia must strengthen its capacity for self defence and pursue greater self reliance within the alliance. That will require increased defence investment and bolder leadership.

Australia is a fortunate nation, but fortune is not strategy. The fractures reshaping the global order are no longer abstract or distant. It is not even the end of January, yet 2026 is already proving to be a pivotal year. Australia must respond as the influential actor it is, by rebuilding the balance of its national power, strengthening diplomatic heft, investing in military capability and reinforcing domestic resilience. This moment demands action, not nostalgia. Australia must seize it.