Fittest of the Fit; Health and Morale in the Royal Navy, 1939-1945. By Kevin Brown. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley 2019

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

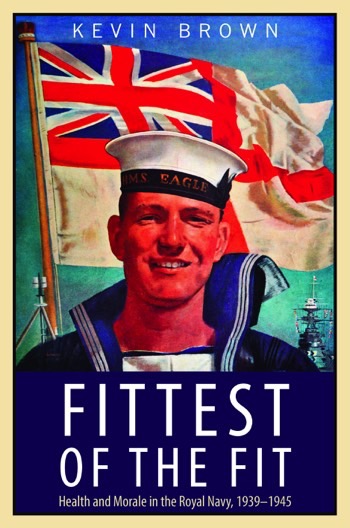

The cover of Fittest of the Fit depicts a bronzed, smiling ‘matlo’, his cap tally showing he is member of the pre-war aircraft carrier HMS Eagle ship’s company, standing on the upper deck. His blue jean collar is ruffled by the sea breeze which billows the huge white ensign behind him. Over his left shoulder can be seen a battleship, possibly the mighty ‘Hood’, then the world’s biggest warship.

This 1930s recruiting poster attracted young men to sign on for at least 12 years to ‘see the world’ through visiting the many ports in the British Empire. There was no shortage of recruits. However, adventure turned to a life and death struggle at sea in September 1939 with the outbreak of war.

Fittest of the Fit is a comprehensive coverage of Royal Navy medical services in World War Two: physical standards, hospitals and sick bays, medical staffs, illnesses and diseases (in-service and self-inflicted), treatment practices and procedures and much more. It also addresses morale and the ways to maintain it by games, sports and entertainment. The over 70 years since the end of World War 2 have seen vast improvements in naval health facilities, habitability in ships and recreational opportunities; this book starkly lays out the health, medical and welfare environment experienced by naval personnel of that now passing generation.

The National Service Act 1939 instituted conscription for the British forces, which included the navy. Physical standards remained initially high but by 1942 many more men were required to man the fleets of new construction ships entering service and physical and educational standards had to be lowered. Medical officers were entered into the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), mostly by conscription. Sick Berth Attendants (SBAs) were selected from the less fit (and less educated) recruits, although permanent service SBAs were of a much higher standard. Doctors in many postings initially found they were under-employed as their ships’ companies were largely young and healthy. But doctors had to learn quickly as there was little navy-specific induction training for many doctors who had come from general practice or had recently graduated. Ship habitability standards were low, particularly in the war construction ships requiring large crews to operate increased armament and ships systems so the medical officer’s skills were routinely directed to preventative medicine and hygiene. However, in action his adaptability and innovation were tested as damage reduced or destroyed the medical spaces and, in some instances, he could only render first aid pending removal of the injured to facilities ashore

Medical staffs were stretched almost beyond tolerance in caring for their ships’ companies in the appalling conditions of the Arctic convoys to Russia, operating in rudimentary conditions in ships under attack, heat stress in tropical waters and many other extreme environmental conditions. Mental breakdowns in action required rapid reactions to stem the danger of morale cracking. Medical officers found they had to counsel these, often temporarily affected, men. One doctor, in a ship under attack on an Arctic convoy, was just as frightened as his hysterical patient but the doctor put the patient in his bunk, kept him warm and overcame his own fear by comforting the sailor who later returned to duty. Of course, there was no trauma counselling, as we now understand it, and no training for medical staffs in how to deal with mental incapacity.

Medical and drug advances made during the war improved the range of treatment: plastic surgery and the miracle drug penicillin being examples. But malaria, venereal disease, prickly heat and mental illnesses were just a few of the challenges facing the medical branch. Psychology and psychiatric services were initially not considered to be a priority; however, as the war progressed these specialities were developed for naval applications.

The book starkly describes the pitfalls and temptations of the wartime sailor’s life; not the least of which was venereal disease which endangered the operational capability of some ships. On the other hand, arrangements for raising morale such as sports, games and entertainment and other wholesome diversions made wartime naval service a little more bearable.

Royal Navy ships had ‘broadside messing’, whereby ‘cooks of the messes’ fetched meals from the galley and brought the food to their respective messes. With the introduction of US ships into the RN, mainly escort aircraft carriers, the cafeteria system became a more efficient messing system, although many claimed that the traditional system engendered loyalties among messmates. The book gives some examples of differences in US ships; while American sailors’ living conditions were very austere, they had superior on-board services compared to RN ships. Every US sailor had a bunk, whereas wartime RN sailors slung hammocks and, where the crowding was too extreme, slept on the deck under tables.

Apart from the medical aspects of surface ships, the book discusses the development and practice of aviation medicine for the Air Branch and medical care for submariners. There were no medically trained personnel in RN submarines; the coxswain was given rudimentary first aid training, although submarine depot ships had full medical staffs.

Fittest of the Fit is a very readable book and provides a most comprehensive coverage of the vast Royal Navy in World War 2. As the RAN was organisationally the same as the RN, and had British ships, Australian naval medical staffs and ships’ companies shared many of the same experiences.

This book is a very human story and should interest not only medical professionals and the wider naval and military community, but anyone interested in large and complex organisations operating under extreme conditions and stress. Your humble reviewer can do no less than highly recommend Fittest of the Fit.