By Euan Graham*

For all the talk about the South China Sea’s complexity as a security issue, its geopolitical significance to China is simple: China wants to condition Southeast Asian states to subordinate status. Southeast Asian countries would do well to consider this when assessing Beijing’s motivations and behaviour. From: The Strategist. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

It’s common for speakers at regional conferences to present the maritime environment in terms of complex, cross-cutting transnational security challenges, such as illegal fishing, critical seabed infrastructure, marine pollution, cyber, climate, autonomy, energy exploration and others. (The list expands continually.)

The importance of cooperation and adherence to international law remains a staple theme of such gatherings. Yet advocates of regional maritime cooperation struggle to name new initiatives. The widely referenced Malacca Strait Patrol, for example, is two decades old. It is also telling that the lexicon of power and competition has gradually crept back into session titles. Phrases such as ‘geopolitical implications’ and ‘armed conflict’ were an uncommon sight at maritime conference agendas 15 years ago. This is no longer the case.

Southeast Asian analysts and security practitioners know that the regional security environment is deteriorating, but they remain reluctant to acknowledge the source of the problem head-on. Some have convinced themselves that great-power competition between the US and China is their primary security challenge, rather than domination by the latter. This manifests in a collective view that conflict avoidance is ASEAN’s primary security objective, more than order preservation—though these are not necessarily mutually exclusive aims. Nowhere is this more evident than in the South China Sea.

In geopolitical terms, the South China Sea is best thought of as an arena. The core game within this arena is between China and Southeast Asia. Beyond access to seabed resources and any intrinsic significance of the sea itself, China’s strategic purpose is to establish dominance over Southeast Asia through repeated conditioning.

Australia, Japan, the US and some European countries are also players in this game. They recognise that their own security will suffer if China successfully resets its relations with Southeast Asia in hierarchical terms, at the expense of respect for sovereign equality and international law. They rightly fear that China aims to eject the armed forces of non-littoral states from the South China Sea, hence their preoccupation with freedom of navigation. But these nations also rely on political support from Southeast Asian countries to legitimise their presence to a significant degree.

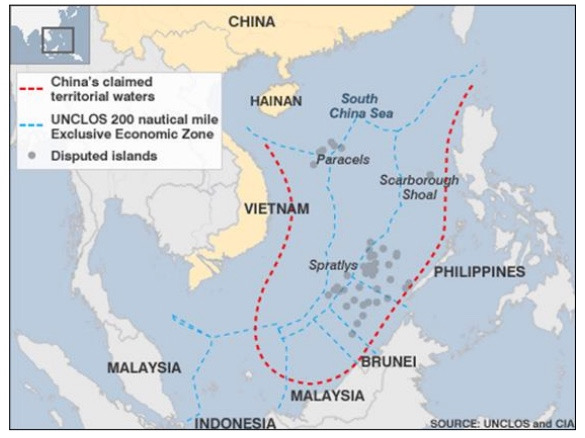

In relation to the South China Sea, Southeast Asia’s core group of states is composed of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. The latter two are Southeast Asia’s frontline territorial claimants and are most directly exposed to Chinese pressure tactics. Vietnam’s geography makes it uniquely vulnerable to any impediment on navigation or commercial activity in the sea. China’s current focus is to isolate the Philippines as far as possible within ASEAN, since Manila has publicly defied Beijing’s attempts to establish dominance and has revived its military alliance with the US. Chinese participants at the conference made this focus clear.

Brunei and Indonesia do not have territorial disputes with China, but Beijing claims overlapping jurisdiction within both countries’ exclusive economic zones, based on its dashed-line claims. Jakarta has long maintained that it has no maritime boundary dispute with Beijing, as it has treated China’s claims as without legal foundation. So the admission to ‘overlapping claims’ in last November’s joint statement during Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto’s inaugural visit to Beijing was a surprising concession to China’s dominance game. Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry maintains that its position on the South China Sea is unchanged. But if Chinese firms can pursue ‘joint development’ based on the November statement, Beijing can claim to have eroded Jakarta’s resolve.

Brunei has proceeded more cautiously on the question of overlapping maritime boundaries. But, in February, Brunei and China jointly agreed ‘to cooperate in the development of resources in mutually agreed areas, on a without prejudice basis to legal positions of the respective countries under international law’. Such development could include joint fisheries activities or hydrocarbons extraction. Whatever form it takes, China is likely to treat such overtures from Southeast Asian claimants as tacit concessions.

Malaysia occupies a middle position among ASEAN claimant states. China claims Malaysian-occupied territory in the Spratly Islands and disputes Malaysia’s jurisdiction within significant portions of its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf. China behaves less aggressively towards Malaysia than it does towards the Philippines and Vietnam. But China’s coast guard maintains a continuous watch inside Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone and exerts physical pressure to deter Putrajaya from developing untapped seabed energy resources within Chinese-claimed areas. One Malaysian participant at the conference floated a proposal for Malaysia to pursue joint energy development with China, without formally acknowledging disputed jurisdiction—similar to Brunei. This is a personal view, not reflective of Malaysian government policy, but Chinese participants will perceive it as further evidence that Southeast Asia’s collective resolve is weakening.

The rest of ASEAN has lower, less direct stakes in the South China Sea. Cambodia and landlocked Laos are already dominated by China to a considerable degree. Singapore, though not a claimant state, relies heavily on freedom of navigation and actively facilitates access for the US Navy and its allies, including Australia through the Five Power Defence Arrangements. Thailand and Myanmar, especially, are less invested. Their main interest is the ASEAN-China Code of Conduct. Frequently dismissed as irrelevant, the code nonetheless serves Beijing’s interests as a useful conditioning tool, since it binds the whole of Southeast Asia (except East Timor) into a seemingly endless diplomatic process. The code’s torturous lack of progress repeatedly demonstrates to ASEAN’s members that negotiations on a draft code have no practical constraint on China’s strategic activities.

China’s quest for dominance in the South China Sea is not about resources nor any single maritime issue; in essence, it isn’t about the sea at all. Beijing’s geopolitical aim is to condition Southeast Asian states, individually and collectively, into accepting subordinate status. If it can achieve this without fighting, the likelihood is that the South China Sea will remain tense but stay below the threshold of armed conflict.

With the standout exception of the Philippines, things are currently trending in Beijing’s direction. Indeed, from Beijing’s perspective, ASEAN’s collective trajectory might be summarised as ‘losing without fighting’.