In the latter part of the 20th Century a small number of maritime strategists emerged whose origin was as long serving naval officers. These practitioner strategists, such as Admiral Stansfield Turner USN, brought a practical and experiential approach to maritime strategy. Another such retired flag officer was the British Rear Admiral Richard Hill. His book Maritime Strategy for Medium Powers became a classic work and not surprisingly resonated strongly in Australia. In April 1988 Richard Hill was in Australia and the ANI President, Commodore Ian Callaway, prevailed on him to speak to a well attended gathering organised by the ANI in Canberra.

The audience included a large contingent of midshipmen from the Australian Defence Force Academy. Rear Admiral Richard Hill’s presentation, “Maritime Strategy for Medium Powers” was soon published in the May 1988 edition of the Journal of the Australian Naval Institute and is reprinted below. It makes for interesting reading in the early years of AUKUS.

Maritime Strategy For Medium Powers

By Rear Admiral J.R. Hill RN*

What is a Pom, whose spent only a few days in Australia in his life, going to talk about that can concern you much? Are the defence problems of our two countries, at either end of the world, at all similar? Is there such a thing as a medium power anyway?

To answer the last question first, well, quite a few critics have picked it up and most of them have grudgingly admitted that there is such an animal although describing it is difficult. Perhaps we can do a bit better than that. Power is the ability to influence events. A superpower is able to influence events in a comprehensive way, through economic clout, cultural influence and military activity. A small power can influence events by its own efforts in only the most limited way; ultimately, it lives under guarantee. But the states in between, they have to be brave as lions and as cunning as foxes because they do have some ability, some potential, and they have to choose how best to deploy it in their interests.

Vital Interests

It’s extraordinary how seldom these get stated in strategic documents; they haven t appeared in British Defence White Papers for many years, but then you are pretty lucky it they mention Britain at all in a strategic context; all the references are to NATO or Europe. But a medium power, it it regards itself as an independent sovereign state, needs to look carefully at its vital interests, and actually the irreducible ones are quite shortly expressed in the UN Charier; Territorial Integrity and Political Independence.

They are both, I think, more easily grasped in this great continent than in the old and complex set-up the other side of the globe, but the principles for safeguarding them are much the same. Territorial Integrity demands the security of frontiers, whether land or sea, and the military element is prominent. Political Independence is a much subtler matter, and requires a complex of economic and diplomatic measures backed by military power.

That doesn’t exhaust the catalogue of vital interests for a medium power. For you can have territorial integrity and political independence and still be a pretty rotten place to live; I could name you a few, but not on the record. Most medium powers will look (or the betterment of their peoples, and for that they need to participate on reasonable terms in the traffic of the world; its production, manufacture, trade, commerce and culture. That demands access to routes and markets. In sum, it is an undoubted vital interest to a medium power. Each individual fragment may not be thought of as a vital interest but beware dominoes. Lose a bit here, a bit there, and suddenly it looks shaky.

Threat

It’s at this point, having defined vital interests, that one ought to start looking at the threat, and not before. Starting with the Threat is one of my particular betes noires. Threat to what, pray? To vital interests is the answer, so you must define the vital interests first. So where is the threat to the vital interests of a medium power? First there’s almost bound to be a threat from one or other of the superpowers. It may be laid a long way back, but in the nature of world economic, political and strategic systems it will be there. When such a threat becomes active, then a medium power is in big trouble. It will need to engage the other superpower on its side.

But there will be other threats, almost certainly, and they may be much more immediate than superpower threats. For many states, they will be directly across land frontiers. Many of the Latin American states have festering border disputes and Israel – which I do regard as a medium power, for reasons which I’ll come back to in a minute – is embattled, but none of these is directly to do with superpower threat. For other states, threats are of a less absolute order; they are to do with discriminatory practices against trade or shipping, the knock-on form from other peoples’ wars, nibbles at outlying dependent territories.

Now it’s a fact of recent history, of history since 1950 I should say, that superpowers are increasingly reluctant to pick up the tab; certainly in local conflicts when non-superpowers are involved, and even when the other superpower is involved but their own vital interests are not seen to be threatened. The Nixon Doctrine was simply an articulation of a process of thought that had been going on for some time; and the Brezhnev Doctrine, though at first sight showing a more interventionist policy than had hitherto been declared, in fact limited its scope to states already firmly in the socialist camp.

So what is a medium power to do? How is it to realise its military potential so that its vital interests may be safeguarded? In my view it must make itself able to do two things; to protect itself against threats where no help can be expected from elsewhere; and in enough strength, to convince the helper – typically a superpower – that it must come in.

I sum this up in my book – and I promise not to refer to it often – as to create and keep under national control enough means of power to initiate and sustain coercive actions whose outcome will be the preservation of its vital interests. You will of course perceive that means of power and coercive action don’t confine themselves to military measures, and I should be the last to suggest that the exercise of power can ever be confined to the military field. Economic diplomatic and even cultural measures are part of the process.

But before I leave it, I’d like to draw particular attention to two other words national control. It’s in the nature of a medium power that its interests are not coincident even with those of its closest friends. There must therefore be no institutional power-of-veto on their part, and the medium power must have the ability to command its own resources in a crisis. The keyword is autonomy not absolute, since this is the prerogative of superpowers and, arguably, is illusory even tor them but significant and sufficient.

By that token, you see Israel does turn out to be a medium power. Tiny though it is, of very limited population and domestic product in world terms, it nevertheless harnesses enough resources – including, in its case, unique individual loyalties and sources of money outside its own frontiers – to maintain control of its own destiny.

How then does the general thinking which bears, as you’II already have detected, a striking resemblance to the self-reliance which has been an increasingly prominent theme in your own defence policy over the past ten years translate into the maritime field.

First and of course, most importantly, the maritime element of strategy must be consistent with the rest of national strategy. I doubt if it was ever right to talk about a maritime strategy or a continental strategy; even in the days of the elder Pitt. Britain took a very close interest in the continent of Europe and tried to ensure a balance of power there – by way of subsidy if not of expeditionary forces – while her predominantly maritime strategy established Britain’s primacy overseas. Nowadays even that level of emphasis is not open to many medium powers. There is a distinct maritime element nonetheless, and it has its own special character.

Because the tools of the medium-power strategists trade are, it seems, sharper and better defined when you are talking about the sea. I’m talking here of conceptual tools of course – the material we shall reach later.

Deterrence

What then are the concepts a medium power can use to guide it in the best use of limited resources to preserve vital interests at, and by sea. First, of course, there is the very general idea of deterrence sufficient strength to convince a potential opponent that military action will be unprofitable for him. The strength need not be all military, need not be all national, but as I’ve implied, the medium power is constantly in the position of having to assess how much it can rely on allies and on non-military means of coercion.

Sea Use And Sea Denial

Then there are the purely sea-related concepts of sea use and sea denial. Most developed nations tend to want to use the sea; indeed the ability to use the sea is one of the most satisfying definitions of sea power. If they want to use it against opposition, they must be prepared to protect such use or harness allies in its protection. Sea denial is a sharper thing, but it is more generally applicable than one might at first think; how about fiscal and immigration control, let alone the ability to defeat a threatened military invasion.

But those concepts, of deterrence, sea use and denial, are not of much use in the management of limited resources without further ordering. Well, of course you can then use scenarios to develop your military organisation. But scenarios have often proved faulty in the event, and can produce such inflexible force structures, that in my view they are largely discredited as a basis for military planning. You can of course use them to test force structures that have been evolved using other processes, and that. I believe, is their proper function.

The further ordering that is needed lies rather in two other sets of concepts; those of Levels of Conflict and of Reach.

Levels Of Conflict

Now you can complicate anything ad nauseam it you want to, and when dealing with levels of conflict it’s quite easy to get into artificialities like Herman Kahn’s 39 steps in the ladder of escalation So lets try to keep it simple and elegant and think of four levels of conflict only.

The first I call Normal Conditions. It would be nice to call it peace, but it wouldn’t be accurate because normal conditions in international relations are more those of compensated tensions than of true peace. We can describe normal conditions though change occurs in a controlled way aided by processes of negotiation, no use of force takes place except at internationally accepted constabulary levels; and threats of force are confined to the normal processes of deterrence.

So to keep this equilibrium, what does a medium power require of its forces in the maritime sphere. To take the deterrent point first, forces must clearly be capable and ready; and that includes readiness to move to a higher level of conflict if it need be. There are several components to that readiness; material state, state of training, a sufficient intelligence and communications base. All these can, and must, be built up and maintained in normal conditions if deterrence is to be effective.

There are other things to be done. The support of municipal law by exercising the necessary enforcement at sea is a charge on maritime forces. The need is for adequate surveillance and the capacity to inform, warn, board, inspect and, if necessary, detain. The potential area to be covered has, as well known, been much increased by the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention Economic Zones out to 200 miles from the coast, archipelagic waters regimes for certain states, different and better-defined regimes for passage of international straits and the territorial sea, have all sharpened the constabulary task.

Finally, there’s the more elusive concept of naval presence. Journalists tend to call it showing the flag, academics – naval diplomacy; naval officers opt for the more generalised term Presence because they’ve been there – and Being There is what it so often is. I do not think there is a better example of what I mean than the Soviet naval presence in the Indian Ocean in the late 1960s and 1970s. The squadron was not of great strength either numerically or in force of arms; it spent a lot of its time at anchor and paid relatively few port visits; but it was there, it laid the base for a much more forward policy in parts of Africa, was a significant component in the relationship with India; and I dare say never out of American thoughts for long. It was a classic presence operation. But when I say that, I don’t mean that such operations are a prerogative of superpower. A medium power has few better ways of showing where it considers it vital interests to lie.

Lets move on now to the second level of conflict: Low Intensity Operations. These I define as operations which never merit the title of war are limited in aim, scope and area, and are subject to the international law of self-defence. In practice they may include sporadic acts of violence on both sides.

The aims of low intensity operations are likely to be expressed in political, or even economic, rather than military terms. The Royal Navy’s Armilla Patrol in the Gulf and its approaches has the aim of ensuring the lawful freedom of passage of ships under British jurisdiction. I’ve invented that. I have not read the Op Order, but it it is not phrased like that wed all be surprised.

And the limitation in scope is governed by the two great principles of self-defence – necessity and proportionality. These are based in a great case of 1839 when the Canadians, tired of terrorism by marauding bands from the USA, crossed the Erie River and cut out an American supply vessel called the Caroline, with some loss of life. She was set on fire and drifted over Niagara Falls – a brave sight. The American Secretary of State, Webster, protested to Britain through Ambassador Fox, requiring Britain to show a need overwhelming, immediate, leaving no choice of means and no moment for deliberation, and that the raiders did nothing unreasonable or excessive, since the act, justified by the necessity of self-defence, must be limited by that necessity and kept clearly within it. As a matter of interest, in a subsequent exchange of letters it was accepted that these requirements had been met in the Caroline case.

These principles are reflected in the Rules of Engagement which govern forces taking part in low intensity operations. These will often, in the eyes of the military, amount to orders to fight with your hands tied behind your back, don’t fire until he has fired at you or, as the Foreign Office phraseology will have it, has committed a ‘hostile act’. They may be relaxed once a pattern of violence emerges; then, maybe, you are allowed to take action once hostile intent has been demonstrated. But how demonstrated? That’s a matter for interpretation by the commander on the spot. At least maritime forces come in discrete packages and can’t merge into the landscape as they can on land.

Because Rules of Engagement are a politico-military necessity, it is necessary to honour international law. It is also necessary to persuade the world that one is not the aggressor, and not firing the first shot gives a powerful premium. It is, finally, necessary to keep the conflict at manageable proportions so that a solution by negotiation remains a possibility.

This leads me to the third kind of limitation in low intensity conflict, that of area. I’m not greatly enamoured of Exclusion Zones on the Falklands pattern. The idea of a sort of Jousting Area appeals to some tidy-minded military men but conflict is not a tidy business and outflanking is all too possible a risk I tend to think that in low intensity operations the limits of the area are likely to be defined de facto by limitation of the aim, and in such operations its reasonable to expect the aim to be well understood by both sides.

There have been plenty of low intensity operations at sea in the past three decades major case studies in a thesis I did a decade and a half ago included the Anglo-Icelandic so called Cod Wars, the Indonesian Confrontation, the dispute over the Gibraltar Waters, the Beira Patrol; and you could have added several others even then. Since that time there have been the Armilla Patrol, several forays in support of Belize, and a lot of anti-gunrunning and anti-illegal-immigration work spread from Hong Kong to the Irish Sea. That was just the Brits.

You can categorise low intensity operations on this evidence into sea use – which includes demonstrations of right or resolve, amphibious landings by invitation, the evacuation of nationals, and ensuring the passage of shipping against sporadic violence – and sea denial, which includes counter-gunrunning, counter-piracy, counter-infiltration by sea. the protection of offshore installations.

What qualities do you need in the forces carrying out such operations? You must be able to get and process information – from long-term intelligence to warning of imminent attack. Your forces must command a wide spectrum of violence, from the finely discriminating to the lethal. It will be as well if they are visible and non-sinister – for you are on the side of the angels – aren’t you. They must have very good communications, between each other and back to headquarters. Finally, those up front must be backed by sufficient strength – the age-old military principle of cover – in case reinforcement or escalation is required.

Which leads us on, inevitably, to the third level of conflict, which is Higher Level Operations These I define as active, organised hostilities involving, on both sides, fleet units, and or aircraft and the use of major weapons.

That does not mean they are unrestricted. There are still limits to aim, scope and area. But they are all likely to be different from the limits of low intensity operations, and this actually makes a transition from low intensity to higher level a quite difficult thing to manage.

Let me explain in terms of the aim. The aim of a higher level operation is likely to be expressed in military terms. So in 1971 the Indian directive might have been; “Blockade East Pakistan attack and sink Pakistani ships in Karachi Harbour”. In 1974, the Turkish aim – “Occupy the northern half of Cyprus”. In 1982, the British ‘Retake the Falkland Islands.” Crisp, military aims. That doesn’t mean there will be no rules of engagement. They will particularly be concerned to limit escalation into more dangerous and destabilising modes of conflict. Nor does it mean there will be no limitation of area, though, here again, I must express my distrust of too mechanistic an approach. It is more than arguable that the Falklands Exclusion Zone was responsible for the political rumpus over the sinking of the General Belgrano. Had the zone not been declared, the sinking would have been seen for what it was, a justifiable military action in the face of overwhelmingly demonstrated hostile intent and, indeed, hostile acts by Argentine forces the day before.

What then are the principal types of higher level operation? They fall again into sea use and sea denial: sea use includes the passage of shipping against opposition, amphibious landing, the bombardment of the shore, sea denial can include the denial of whole geographical areas, including blockade, or denial of the area round a moving datum. In some cases the use and the denial objectives of an operation may merge, and then indeed you may get a battle. Battle is not an inevitable outcome of higher level operations; but if a medium power plans never to have a battle, it may get one on very unfavourable terms.

So inevitably, one needs to look at the requirements in that light. In higher level operations, lethality is at a premium. But so is information gathering and processing, and so are communications. Finally, the ability of the command to dispose and govern its forces to the best advantage is a force multiplier of first order.

On the fourth level of conflict, General War, I do not have much to say. Whether heresy can consist of not having much to say, I don’t know; if so, I am a heretic. I don’t think a medium power has much to say about general war because it is certain to be dominated by the superpowers; and the contribution a medium power can make will be simply an extension of its higher level capability.

With one exception. A few medium powers now, and surely more in the future, can deploy nuclear weapons at sea. A decision to develop strategic nuclear weapons is a momentous one for a medium power, it does represent a very considerable outlay of defence money which could be spent in other ways, and almost certainly the diversion of some general purpose forces to the protection of the most strategic nuclear weapon platforms. On other hand, it can be regarded as a supreme national deterrent safeguard, the epitome of self-reliance.

Tactical nuclear weapons – and tactical is not a misnomer at sea – have a different rationale. It is one which I am bound to say I have never heard well articulated in the West, and I am not sure how valid it is. It goes something like this. We are not sure how effective our weapon systems will be in war; they may not be good enough to impose sufficient attrition if we use conventional munitions; we must have something of the greatest possible lethality to use if we get desperate; anyhow the other fellow has got it, so our possession of these things adds to our deterrent structure.

Now whether that justifies the medium power in possession of tactical nuclear weapons for use at sea is, to me, not at all certain.

I turn now to the other governing concept of maritime strategy for medium powers, that of reach. Reach we can define as the distance from home bases at which operations can be carried out. Immediately the cry goes forth: ‘what sort of operations,’ and it is, indeed, a good question. For example, presence operations in normal conditions are undertaken by quite small navies at great distances from their shores. Latin American sail training ships are an example. On the other hand, vital interests indeed are needed to dictate a requirement to mount amphibious operations half way across the world.

When you combine the question how far, with the question how much you are getting quite close to the heart of a medium power’s maritime strategic problems. At long reach, all the practical and resource constraints felt by a medium power are tightened. Can one afford what is needed not only to mount but to sustain operations of a certain level at such a reach. Can one afford not to? What are the limits to be set, and the risks one is prepared to take. The two are interactive.

Before coming to some conclusion how these dilemmas are to be managed, let me say a few words about material. A rather embarrassing consequence of the levels-of-conflict approach to naval forces is that the different kinds of unit turn out to be of very varied utility at different levels.

The surface ship. Visible, capable of sustained operation, good communications and data handling, non-sinister, a wide variety of sensor and weapon systems. Therefore, a flexible and essential instrument for normal conditions and low intensity operations. At the higher level and beyond all too easily detectable, all too vulnerable to both missile and underwater attack; but still a considerable purveyor of threat to the enemy and an instrument of sea-based command.

The submarine. Again, capable of sustained operation, though it must return to a secure base at the end of its patrol. Its greatest virtue is concealment. Its underwater sensors are good, often the best, but its communications with anything in the atmosphere are bad and it doesn’t want to use them anyway. Its weapons are lethal and its image sinister. Consequently its utility in normal conditions and at low intensity is confined to covert surveillance and cover – a stick to shake – but at the higher level it comes into its own.

The combat aircraft. It has fantastic tactical mobility but limited endurance in the air. It has good communications but things happen fast in the air and missions are often preset. It can mount many different weapons, all of high lethality, and the accuracy and discrimination of those weapons has not historically turned out to be exactly surgical. Again, therefore, it is by no means an ideal instrument for low intensity operations.

Surveillance aircraft, both fixed and rotary wing. These really are all-level vehicles, essentially alike in normal conditions – particularly in the constabulary tasks, surveillance, search and rescue, communication flights; at low intensity for extension of the warning envelope, for monitoring against submarine activity by the other side: and at the higher level for the whole gamut of the anti-submarine process from detection to prosecution of contacts, for early warning of air and surface attack, for linking communications.

So how does the medium power put all this together into a maritime organisation that can safeguard its vital interests at and by sea?

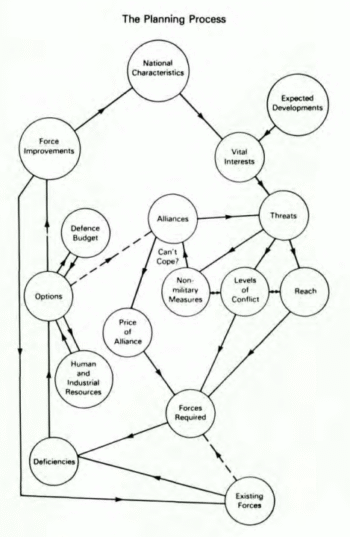

The first thing to do, clearly, is to define those vital interests and to assess how they may change during the period for which one is planning – and that of course ought to be about thirty years, but you won’t find many crystal. ballgazers prepared to go that far. Then you must look at the threats to those vital interests – and the predicted changes in that field Then comes a most critical part of the analysis: the part non-military measures might play in safeguarding against the threat (countries, after all, have bought a large part of their security before now, and at least one medium power still aims to do that), and the part to be played by maritime forces analysed in terms of level of conflict and reach. The overall aim, of course, is to construct an organisation that will deter any military initiative by an opponent.

Can you do that on your own? Almost certainly not, because somewhere lurking there will be a threat larger than a medium power can cope with certainly at the higher level, and at long reach. If you cannot cope, you need an ally; and you must be prepared to pay the price for alliance. It can be paid in money; but you might prefer to spend that on your own forces. Most medium powers will prefer to pay in a combination of three other ways: strategic position and facilities related to that; diplomatic support; and contributory forces. You know a good deal about the first two in Australia, as indeed we do in Britain, and I shan’t labour them. But the third is singularly relevant to my theme.

You see, if a medium power emphasises its alliance commitment to the extent of saying that its forces are a contribution and that only, it is very likely to get a force structure that is not suited to its national needs. It is almost bound to be optimised to a level of conflict higher than a medium power would want; it will be looking at threats that the medium power would not regard as the most immediate, and it might be dangerously dependent on certain elements of the ally’s naval forces. AEW comes irresistibly to mind it was because the Royal Navy was regarded essentially as a contributory naval force for NATO that it had no Airborne Early Warning in the Falklands.

What, after all, is a medium power trying to do with its alliance? There is nothing altruistic about this. It wants its ally on its side when its vital interests are threatened and it can’t cope on its own. Historically, there has been no rush by allies to join in such circumstances. They have to be convinced that the medium power means business – so it must be able to fight on its own at least long enough for the ally to stir. The process by which allies enter war is best thought of as a sort of catalysis – not just the operation of a few procedural levers.

So, in my view, the price of alliance in terms of force structures has to be carefully contained, and the other means of paying must be exploited as much as possible. And then, by a careful balancing of resources, technology, manpower, and a proper judgement of the limits of the possible and the risks that are permissible, the medium power can plan and produce nationally-based maritime forces that will help it decide its own destiny.

Britain and Australia

How have my country, and yours, done? Two interesting case studies, you may think. Britain has for almost exactly 20 years had a defence policy based on a contribution to NATO. Everything had to be justified on that ticket. Yet by one means and another, the Royal Navy not only brought into being a force of nuclear-powered submarines – which of course could be justified on the NATO ticket – but kept efficient operational communications, high-grade anti-submarine assets, air defence that gave an opponent formidable problems, ships and troops capable of amphibious assault, backing them all with the best seagoing logistic organisation outside the USA; and even, in a brilliant staff counter-attack, re-provided fixed-wing aircraft organic to the fleet for attack and defence. It was a muddled, illogical and peculiarly British rearguard action, but happily it worked just well enough to meet the test of 1982. Two years on, it might not have done, for much was about to crumble. The dykes have remained patched since.

Australia has unique problems. The basic ones are that it is very big, and therefore difficult to defend. But also, it is very big and therefore difficult to attack. Those nettles, it seems to me, have been grasped – with many others – by the reports of Dibb in 1986 and the Department of Defence in l987; and, again it seems to me, the strategic basis of those reports is entirely sound in terms of medium power. I now must make a total disclaimer of collusion between Dibb and myself. In fact, we published our work, with its remarkable similarity in thought about levels of conflict and reach, at almost exactly the same moment in 1986, and we did not communicate until the IISS Conference in the autumn of that year when we approached each other over the horizon waving our respective volumes like signal flags. Indeed, if I have a criticism of Australian maritime policy it is not on the strategic side but on the implementation of the strategy in material terms. Is that well-judged area of interest covered by force that can be sufficiently brought to bear. Or by warning of enough certainty. No doubt there are many other questions, as I said, your problems are of large dimensions.

But an outsider, looking in on your great country, sees your new policies as based on cool self-appraisal and sound forward thinking. With those as a basis, and the growth and vigour that is apparent everywhere, the material side must come right, given reasonable deployment of resources. In congratulating you on your bicentennial, then, I also have to congratulate you on a notable strategic coming of age.

About the Author

Rear Admiral Richard Hill was born in 1925 and joined the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth in 1942 and first went to sea in 1946. He had an unusual naval career. His early service was mainly in destroyers and frigates and went on to specialise in navigation. He was promoted to commander in 1962 at the age of 37, which was relatively young for that time. He was, however, placed on the ‘dry list’ and so ineligible for sea command. In 1972 Richard Hill was made a Defence Fellow at King’s College, London and wrote his thesis on ‘The Rule of Law at Sea’. The following year he was part of the British delegation to the third UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III). He later excelled both as Defence Defence and Naval Attaché at The Hague and in a series of appointments in Whitehall. He retired as a Rear Admiral in 1983.

Following his naval retirement Richard Hill served as chief executive of the Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court. He found time to serve as editor of the Naval Review (1983-2002), Chairman of the Society for Nautical Research (1994-1999) and Vice President of the Naval Records Society (1997-2001). In 2000 he was the recipient of the Mountbatten Maritime Prize.

Beside his landmark Maritime Strategy for Medium Powers (1986), Richard Hill wrote or edited over a dozen books and wrote numerous articles and naval entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB). He died in 2017 and in 2021 he himself became an ODNB entry.