The UK Nuclear Deterrent Since 1940: Lessons from the Past? (Approx 7600 words)

By Admiral Rt Hon Lord West of Spithead GCB DSC PC*

Introduction

Few people dispute that the nuclear deterrent is the guarantor of last resort for the UK’s national security. But our journey to this point has not been straightforward, and it has not come without costs for our conventional defence programme.

By surveying the history of the British nuclear programme in today’s context, a few valuable lessons emerge. For one, we must acknowledge how reliant the servicing, development, and operation of our nuclear programme now are on US support and goodwill. Any fundamental change to that status quo would have vast implications.

But the corollary of that is that the UK has, on many occasions, navigated turbulence effectively in both the UK-U.S. strategic relationship, and the Transatlantic security environment. We certainly must call on this muscle memory today, as recommended in the recent Strategic Defence Review (SDR). (1) Lastly, any marginal increase in the prospect of a nuclear capability gap emerging between European NATO and Russia – as a result of the U.S. withdrawing even partially its nuclear umbrella from the Continent – makes bolstering our conventional military capabilities all the more vital. The only means of doing so is to increase defence spending substantially.

It is commonly accepted among experts and military planners that developing a homegrown strategic nuclear weapon is unfeasible, given the costs and time involved (£120 billion over 25 years). Developing a Non- Strategic Nuclear Weapon (NSNW), whilst financially and technologically more feasible (£7 billion over 10 years), also has significant obstacles – not least our obligations to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). To withdraw from the Treaty would, at the least, require close coordination with European partners.

A final observation from history. The costs of expanding our nuclear deterrent may currently seem insurmountable. But it is worth remembering that the 1940s race to develop a nuclear weapon incurred enormous costs too. We did that then because the alternative was unconscionable: to be exposed to nuclear coercion and attack by our adversaries. If history were to repeat itself, we would have little choice but to make the same decision.

The UK Nuclear Deterrent Since 1940: Lessons from the Past? I In 1952, the United Kingdom became the third country (after the US and the Soviet Union) to develop and test atomic weapons, followed by France and China. Now India, Pakistan, Israel, North Korea possess warheads and countries such as Iran are within easy reach.

It is worth looking back at the history of the UK deterrent and in particular the political imperatives and pressures.

By 1940, a number of British scientists and German refugee scientists had discovered the neutron and fission and calculated that 1 to 10 kilograms of uranium would explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite. They produced a memorandum to this effect which led to establishment of the MAUD Committee to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible.

By July 1941, the MAUD committee had produced two reports that an atomic bomb was not only technically feasible, but could be produced before the war ended, perhaps in as little as two years and recommended pursuing the development of an atomic bomb as a matter of urgency. It also expressed concern that that the resources required might be beyond those available to Britain. This scale of scientific and technical skill as well as costs have been recurring themes in our possession of the ‘bomb’. A new directorate known as ‘Tube Alloys’ was created to coordinate this effort.

In July 1940, Britain had offered to give the United States access to its scientific research and briefed American scientists on British developments. The Americans had a project (later named Manhattan) that was smaller than the British, and not as far advanced.

We considered producing an atomic bomb without American help, but it would require overwhelming priority, would disrupt other wartime projects, and was unlikely to be ready in time to affect the outcome of the European War. Given these internal limitations, Churchill and Roosevelt signed the Quebec Agreement in August 1943, merging the two national projects. The Quebec Agreement specified that the weapons could only be used if both the US and UK governments agreed.

Truman had to get UK agreement before he could use the bombs on Japan. The 19 September 1944 Hyde Park Agreement accepted that both commercial and military cooperation would be extended into the post- war period, however this was later ignored by the Americans.

With the end of the war, the Special Relationship between Britain and the United States “became very much less special”. The British government had trusted that America would share nuclear technology, which it onsidered a joint discovery, but they did not. The McMahon Act in August 1946, ended technical cooperation. Its control of “restricted data” prevented the United States’ allies from receiving any information. The remaining British scientists working in the United States were denied access to papers that they had written just days before.

Given this setback, most leading scientists and politicians of all parties in the UK were determined that Britain should have its own atomic weapons. Their motives included national defence, a vision of a civil programme for nuclear power (as an aside it is worth noting that we led the world in civil nuclear power—so different today), and a desire that a British voice should be as powerful as any in international debate. Attlee set up the “Atomic Bomb Committee” in August 1945 to examine the feasibility of an independent British nuclear weapons programme and a nuclear reactor and plutonium-processing facility was approved on 18 December 1945 “with the highest urgency and importance”. The Chiefs of staff committee considered the issue in July1946, and recommended that Britain acquire nuclear weapons. In 1947, they judged that even with American help the United Kingdom could not prevent the “vastly superior” Soviet forces from overrunning Western Europe, from which Russia could destroy Britain with missiles without using atomic weapons. Only “the threat of large-scale damage from similar weapons” could prevent the Soviet Union from using atomic weapons in a war. They estimated that 200 bombs would be required by 1957.

In October 1946, Attlee called a meeting to discuss building a gaseous diffusion plant for uranium enrichment and were about to decide against it on grounds of cost, when Ernest Bevin (foreign Secretary) said «We›ve got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs … We’ve got to have the bloody union jack flying on top of it.” The decision to proceed was formally made on 8 January 1947 and was publicly announced in the House on 12 May 1948. It was given the cover name “High Explosive Research”.

Churchill, now again Prime Minister, announced on 17 February 1952 that the first British weapon test would occur before the end of the year.

That test Operation Hurricane involved detonating an atomic bomb on board the HMS Plym anchored in a lagoon in the Monte Bello Islands Western Australia on 3 October 1952. Doing so, Britain became the third country to develop and test nuclear weapons.

This led to the development of the first operational UK atomic weapon, the Blue Danube free-fall bomb. The first Blue Danube bombs were delivered to the Royal Air Force in November 1953, although the bombers to deliver them did not become available until 1955. On 11 October 1956, a Vickers Valiant was the first British aircraft to drop a live atomic bomb when a Blue Danube was exploded in a test over Maralinga, South Australia About 58 Blue Danube bombs were produced, each bomb holding a nominal yield of 15 kilotons of TNT. It remained in service until 1962, and was replaced by Red Beard, a smaller tactical nuclear weapon.

Being so big and heavy, Blue Danube could only be carried by the V bombers, so-called because they all had names starting with a “V”. The three V bombers were the Vickers Valiant, Avro Vulcan , and Handley Page Victor. The V Bomber force reached its peak in June 1964, when 50 Valiants, 70 Vulcans and 39 Victors were in service.

In 1957, a government study stated that although RAF fighters would “unquestionably be able to take a heavy toll of enemy bombers, a proportion would inevitably get through. Even if it were only a dozen, they could with megaton bombs (which had been developed and deployed by US and Soviet Union) inflict widespread devastation.” Although disarmament remained a British goal, “the only existing safeguard against major aggression is the power to threaten retaliation with nuclear weapons.” Churchill stated in a 1955 speech that deterrence would be “the parents of disarmament” and that, unless Britain contributed to Western deterrence with its own weapons, during a war the targets that threatened it the most might not be prioritised. The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan advanced the position that nuclear weapons would give Britain influence over targeting and American policy ,and would affect strategy in the Middle East and Far East. His Minister of Defence Duncan Sandys considered that nuclear weapons reduced Britain’s dependence on the United States. The 1956 Suez Crisis demonstrated that Britain was no longer a superpower, but this realisation increased the value to Britain of an independent nuclear deterrent that would give it greater influence with the US and USSR. Whilst the military target of British nuclear weapons was the Soviet Union, the political target was the United States.

Independent targeting was vital. The Chiefs of Staff believed that once the Soviet Union became able to attack the United States itself with nuclear weapons in the late 1950s, America might not risk its own cities to defend Europe, or not emphasise targets that endangered the United Kingdom more than the United States. Britain thus needed the ability to convince the USSR that attacking Europe would be too costly regardless of American participation. Part of the perceived effectiveness of an independent deterrent was the willingness to target enemy cities.

The government had decided on 27 July 1954 to begin development of a thermonuclear bomb, announcing its plans in February 1955. The first prototype was tested in Grapple 1. in the Pacific on 15 May 1957.

An Operational Requirement was issued in 1955 for a thermonuclear warhead for a medium-range ballistic missile, which became Blue Streak. This was revised in November 1955, with “megaton” replacing “thermonuclear”. The scientists at Aldermaston had not yet mastered the design of thermo-nuclear weapons but had a new weapon and were given verbal approval by the Prime Minister, for a test off Christmas Island on 28 April 1958 before the moratorium in testing. It had an explosive yield of about 3 megatonnes of TNT and remains the largest British nuclear weapon ever tested.

The international moratorium commenced on 31 October 1958, and Britain ceased atmospheric testing for good. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) also came to prominence in 1958 as there had been little knowledge of or indeed opposition to our atomic progamme.

Production of British nuclear weapons was slow and Britain had only ten atomic bombs in 1955 and just fourteen in 1956. At the three-power Bermuda Conference with Eisenhower in December 1953, Churchill suggested that the United States allow Britain to have access to American nuclear weapons to make up the shortfall. The provision on American weapons was called Project E. The agreement was confirmed by Eisenhower and Macmillan, who was now the Prime Minister, during their March 1957 meeting in Bermuda, and a formal MOU was signed on 21 May 1957.

Nuclear weapons had become all pervasive and were seen as war fighters. Four squadrons of Canberra bombers based in Germany were equipped with US Mk7 bombs stored at RAF Germany bases. There were also four squadrons of nuclear-armed Canberras based in the UK, which were capable of carrying either the Mark 7 or Red Beard. They too were assigned to the SACEUR in October 1960. The planned V-bomber force was reduced to 144 aircraft, and it was intended to equip half of them with Project E weapons, so 72 Mk 5 bombs were supplied for the V-bombers.

The McMahon Act was amended, paving the way for the1958 US- UK Mutual Defence Agreement (MDA). Macmillan called this “the Great Prize”. When the MDA came into force, the US agreed to supply the V-bombers with megaton weapons in place of the Mark 5,[ in the form of Mk15 and Mk 39 bombs.

On the 7 July 1960, the Air Council decided on that Project E weapons would be phased out by December 1962, by which time it was anticipated that there would be sufficient British megaton weapons to equip the entire strategic bomber force. Project E weapons were replaced by British Yellow Sun bombs. Project E nuclear warheads were also used on the sixty Thor Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs) that were operated by the RAF from 1959 to 1963.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), the RAF’s bombers and Thor missiles targeted 16 cities, 44 airfields, 10 air defence control centres and 20 IRBM sites. The RAF high command never warmed to missiles, and always ranked them secondary to the V bomber force.

The British Army purchased 113 Corporal Missiles from the United States in 1954. It was intended that they would be equipped with British warheads but Project E offered a quicker, simpler and cheaper alternative.

The US supplied 100 W7 warheads, which had to be drawn from US Army storage sites in southern Germany until arrangements were made for local storage. A British missile, Blue Water with an Indigo Hammer warhead, was developed to replace Corporal. The US offered the Honest John missile as an interim replacement. The offer was accepted, and 120 Honest John missiles with warheads were supplied in 1960, enough to equip three artillery regiments. Blue Water was cancelled in July 1962 and Honest John remained in service until 1977, when it was replaced by the Lance Missile. The US also supplied the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) with 36 nuclear warheads that equipped four batteries of eight-inch howitzers. The British Army deployed more US nuclear weapons than the RAF and Royal Navy combined, peaking at 327 out of 392 in 1976–1978. Additionally, the RAF acquired nuclear depth bombs for its MPAs from 1965 to 1971.

When the Cold War ended in 1991, the BAOR still had about 85 Lance missiles, and more than 70 eight-inch and 155 mm nuclear artillery shells.

The last Project E warheads, including the Mark 57 nuclear depth bombs and those used by the BAOR, were withdrawn in July 1992.

In 1960, the government decided to cancel the Blue Streak Missile programme based on the Chiefs of Staff’s conclusion that it was too vulnerable to attack and thus was only useful for a first strike (and cost was an issue). When it became clear that the Soviet Union’s SAMs could bring down high-flying aircraft, the V bomber force changed to low-level attack methods. Moreover, the Blue Steel (standoff missile that carried the nuclear weapon) mission profile was changed to one of low-level penetration and release. This reduced its range significantly. It was then planned to move to the much longer-ranged US Skybolt.

Macmillan met with Eisenhower in March 1960, and secured permission to buy Skybolt without strings attached. In return, the Americans were given permission to base the US Navy’s SSBNs at Holy Loch in Scotland.

At the same time, work was in progress on a Red Beard replacement for use with the RAF’s TSR2(later cancelled) and the Royal Navy›s Buccaneer.

Ultimately, a warhead was produced in two variants: the high-yield and low-yield WE.177A as a Red Beard replacement, and for use in depth charges and anti-submarine missiles.

The deployment of ships carrying nuclear depth bombs (NDB) caused complications during the Falklands War, and in the aftermath of that war it was decided to stockpile them ashore in peacetime. When the US withdrew its theatre nuclear weapons from Europe, the British government followed suit. The nuclear depth bombs were withdrawn from service in 1992, followed by the WE.177 free-fall bombs on 31 March 1998, and all were dismantled by the end of August.

The Kennedy administration cancelled Skybolt in December 1962 because it determined that other delivery systems were progressing better than expected, and a further expensive system was surplus to US requirements. When the US cancelled Skybolt, the survivability of the V force was highly questionable.This caused consternation as the V bomber force was no longer able to penetrate Soviet airspace and had no suitable standoff weapon.

Macmillan met with President Kennedy and brokered the Nassau Agreement. Macmillan rejected offers of other systems, and insisted (strongly influenced by Mountbatten) that the UK needed to purchase Polaris SLBM. These represented more advanced technology than Skybolt. But more importantly SLBMs gave a second-strike capability because of their invulnerability to attack. The US agreed to provide the UK with Polaris missiles, the only proviso being would be assigned to NATO, although it could be used independently when “supreme national interests” intervened.

The Polaris Sales Agreement was signed on 6 April 1963. The UK retained its deterrent force, although its control passed from the RAF to the Royal Navy. A profound shock to the RAF -strategic attack of the enemies homeland being the whole raison d’etre of Trenchard’s independent service. The Polaris missiles were equipped with British warheads. A base was developed for the Polaris submarines at Faslane on the Clyde, not far from the US Navy’s base at Holy Loch. It was served by a weapons store at nearby Coulport. Under the MDA, the US supplied the UK with not just nuclear submarine propulsion technology, but a complete pressurised water reactor. This was used in the Royal Navy’s first nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Dreadnought launched in 1960 and commisioned in 1963. The first of four Polaris submarines, HMS Resolution was launched in September 1966, and commenced its first deterrent patrol in June 1968. The annual running costs of the Polaris boats came to around two per cent of the defence budget, and they came to be seen as a credible deterrent that enhanced Britain’s international status.

Polaris had not been designed to penetrate anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defences, but the Royal Navy had to ensure that its small Polaris force operating alone, and often with only one submarine on patrol, could penetrate the ABM screen around Moscow. The Wilson Government publicly ruled out the purchase of Poseidon missiles in June 1967, and without such a commitment, the Americans were unwilling to share information about warhead vulnerability. The result was Chevaline an Improved Front End (IFE) that replaced one of the three warheads with multiple decoys and other defensive countermeasures, in what was known as a Penetration Aid Carrier (PAC). It was the most technically complex defence project ever undertaken in the United Kingdom. Chevaline’s existence, along with its formerly secret codename, was revealed by the Secretary of State for Defence, during a debate in the House of Commons on 24 January 1980. By this time the project had gone on for a decade. The final cost reached £1,025 million.

At a time when the Labour Party pursued unilateralism, the Thatcher government in 1982 announced its decision to purchase 65American Trident D5 missiles. The Navy had to lose 25 DD/FF to fund this decision.

The UK’s D5 missiles operated as part of a shared pool of weapons based at Kings Bay in the United States. The US would maintain and support the missiles, while the UK would manufacture its own submarines and warheads. The warheads and missiles would be mated in the UK. Four Vanguard submarines were designed and built. Trident missiles had multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV) capability, which was needed to overcome the Soviet ABM defences.

Each submarine could carry up to 16 missiles, each of which can carry multiple warheads. However, when the decision to purchase Trident II was announced, it was stressed that British Trident boats would carry no more than 128 warheads—the same number as Polaris. In November 1993, the Secretary of State for Defence, announced that each boat would deploy no more than 96 warheads. In 2010, this was reduced to a maximum of 40 warheads, split between eight missiles. The missiles have a range of 12,000 kilometres (7,500 mi).

The first Trident boat, HMS Vanguard, collected a full load of 16 missiles in 1994, but the second HMS Victorious drew only 12 in 1995, and the third, HMS Vigilant, 14 in 1997, leaving the remaining missile tubes empty.

The UK relaxed its nuclear posture after the Cold war: • The stockpile of “operationally available warheads” was reduced • • • • to 225 The final batch of missile bodies would not be purchased, limiting the fleet to 58.

A submarine’s load of warheads was reduced from 96 to 48. This reduced the explosive power of the warheads on a Vanguard class Trident submarine to “one third less than a Polaris submarine armed with Chevaline”. However, 48 warheads per Trident submarine represents a 50% increase on the 32 warheads per submarine of Chevaline. Total explosive power has been in decline for decades as the accuracy of missiles has improved, therefore requiring less power to destroy each target. Trident can destroy 48 targets per submarine, as opposed to 32 targets that could be destroyed by Chevaline.

Submarines’ missiles would not be targeted, but rather at several days “notice to fire”.

Although one submarine would always be on patrol it will operate on a “reduced day-to-day alert state”. A major factor in maintaining a constant patrol is to avoid “misunderstanding or escalation if a Trident submarine were to sail during a period of crisis”.

Since 1968, the United Kingdom has maintained CASD with at least one ballistic-missile submarine on patrol, “effectively invulnerable to pre- emptive attack”. In the Strategic Defence Review published in July 1998, the government stated that once the Vanguard submarines became fully operational (the fourth and final one, HMS Vengeance, entered service on 27 November 1999), it would “maintain a stockpile of fewer than 200 operationally available warheads”.

As of 2016, the UK had a stockpile of 215 warheads, of which 120 were operational. The 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review reduced the number of warheads and missiles for the ballistic missile submarine on patrol to 40 and 8 respectively. The Trident system cost the UK £12.6 billion (at 1996 prices) and £280m a year to maintain.

With the tactical nuclear weapons having been withdrawn from service, Trident was the UK’s only remaining nuclear weapons system. By this time, possession of nuclear weapons had become an important part of Britain’s national identity. Not renewing Trident meant that Britain would become a non-nuclear power and strike at Britain’s status as a great power. A decision on the renewal of Trident was made on 4 December 2006. Prime Minister Tony Blair told MPs it would be «unwise and dangerous» for the UK to give up its nuclear weapons. He outlined plans to spend up to £20bn on a new generation of ballistic missile submarines.

The new boats would continue to carry the Trident II D-5 missiles, but submarine numbers might be cut from four to three, and the number of nuclear warheads would reduced by 20% to 160. He said although the Cold War had ended, the UK needed nuclear weapons, as no-one could be sure another nuclear threat would not emerge in the future.

The 2010 Coalition Government agreed «that the renewal of Trident should be scrutinised to ensure value for money. Liberal Democrats will continue to make the case for alternatives.” Research and development work continued, but the final decision to proceed with building a replacement was scheduled for 2016. After the next election there was already some urgency to move ahead because some experts predicted it could take 17 years to develop the replacement for the Vanguard-class submarines. The vote in Parliament on whether to replace the existing four Vanguard-class submarines was held on 18 July 2016. The Trident renewal programme motion passed with a significant majority with 472 MPs voting in favour and 117 against. The successor class was officially named the Dreadnought Class on 21 October 2016. The keel of the HMS Dreadnought was laid in March 2025 and all four submarines will be delivered in the 2030s, The government released a written statement on 25 February 2020, outlining that the UK nuclear warheads will be replaced and will match the US Trident II SLBM and related systems. The new UK warhead was planned to fit inside the future US Mk7 aeroshell that would house the future US W93 warhead. It would be the first UK-designed warhead in thirty years, since the Holbrook, an Anglicised version of the US W76.

Meanwhile, construction of the £634 million Pegasus enriched uranium facility was suspended in 2018 but the program will be restarted as covered in the recent Defence Nuclear command paper, the £1,806 million Mensa warhead assembly facility is still under construction.

In April 2017 Defence Secretary confirmed that the UK would use nuclear weapons in a pre-emptive nuclear strike under “the most extreme circumstances” Until 1998 the aircraft-delivered, free-fall WE.177 bombs provided a sub-strategic option in addition to their designed function as tactical battlefield weapons. With the retirement of WE.177, a sub-strategic warhead is used with some (but not all) deployed Trident missiles. Risk is that opponents might see it as a strategic strike package and respond accordingly. The 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review further pledged to reduce its requirement for operationally available warheads from fewer than 160 to no more than 120. In a January 2015 written statement, Defence Secretary Michael Fallon reported that “all Vanguard Class SSBNs on continuous at-sea deterrent patrol now carry 40 nuclear warheads and no more than eight operational missiles”. However, on 17 March 2021, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the number of nuclear warheads in the UK stockpile would be increased to 260. This reversed the long-term trend of steadily reducing the stockpile.

Today, the huge cost of the Dreadnought and warhead programme is distorting the defence budget. It is planned to spend £240m at Barrow and £474m at RR Rayneway, plus the build costs for the 4 new SSBNs.

In addition the UK is currently in the process of upgrading its production infrastructure for the Trident warheads. There are three main projects: Mensa, Pegasus and Aurora. Mensa (warhead assembly in AWE Burghfield) and Pegasus (enriched uranium handling and component production in AWE Aldermaston) are expected to cost £2.1 billion and £1.7 billion respectively. Project Aurora (plutonium component manufacturing in AWE Aldermaston) has an estimated completion date of early to mid 2030s, and is costed at £2.3 billion. These projects are planned cooperatively with the US. The withdrawal of American support would thus incur additional costs.

Looking forward, the acute geopolitical uncertainty has combined with the checkered history of the UK’s nuclear deterrent to raise a number of difficult questions for HMG. Below is an analysis of the main issues to address:

What are the implications for NATO Europe if the U.S. withdraws its nuclear shield?

There is yet no signal from any member of the Trump Administration of the intent to withdraw the nuclear shield from NATO Europe. However, as the U.S. launches a bottom-up audit of its global military and diplomatic commitments – with a view to shedding costs – it would be foolhardy not to consider the unthinkable.

The implications of a withdrawal of the US Nuclear shield from Europe would be enormous in security and economic terms. To assess the impact of such a scenario, we must first look at what European NATO states would have to replace.

The US has an arsenal of 1744 strategic nuclear warheads, encompassed in a worldwide delivery system comprised of ICBMs, bombers, SLBMs and B61 bombs already deployed in Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Turkey and Belgium. Accompanying the significant number of warheads, the US also undergirds NATO C3I (Command, Control, Communications, and Intelligence) capabilities along with advanced early warning systems and second-strike capabilities.

Even a marginal increase in the possibility that this central pillar of European security is unstable has shocked European leaders into considering what alternative might be politically, financially and militarily viable.

The SDR concurs that “nuclear deterrence can no longer be considered separately from the wider strategic environment”.2 It is positive that the Government recognises that the nuclear deterrent must be reintegrated into the UK’s overall conception of its strategic posture.

Plugging this strategic deterrence gap against Russia would impose immense financial costs on European NATO. The United States invests heavily in its nuclear forces, spending $51.5 billion on nuclear weapons in 2023 with a budget plan that calls for spending $540 billion over the next 10 years for strategic forces and $430 billion for maintenance.

To estimate the cost of replacing the American nuclear umbrella, there are a couple of scenarios to consider:

- Independent Nuclear Programmes: Developing domestically produced nuclear capabilities requires considerable outlay in research and development, infrastructure, and maintenance. The UK’s Trident program, for example, which is heavily dependent on U.S. technical collaboration, lacks agreement on what happens in the absence of U.S. assistance, and how those conditions would inevitably contribute to costs coming in higher than commitment.

Experts believe the Trident system could be difficult financially and technically to renew. Other European countries are also seriously considering building their own independent nuclear arsenals, taking inspiration from France’s nuclear programme. Poland is a prime example, as Prime Minister Donald Tusk recently stated that “Poland must pursue the most advanced capabilities, including nuclear and modern unconventional weapons”. Of course, this rhetoric also plays well domestically with a large percentage of Poles favouring both developing indigenous nuclear capacities, and over 75% of Poles favouring an increase in defence spending as a percentage of GDP.

- Joint European NATO Programme: The idea of a joint European nuclear program has garnered attention as a way of replacing the U.S.

nuclear umbrella whilst sharing costs across member states. Despite the fact that sharing the financial burden of nuclear capabilities would reduce the individual financial costs of certain countries, a shared program would still require significant upfront costs and navigating a tricky political landscape. Returning to a theme he voiced in 2020, French President Emmauel Macron has recently called for a new “strategic debate” on Europe’s nuclear deterrent, and hinted willingness to discuss merging France’s independent nuclear weapons into a European umbrella, without the need for American funding or technical support. With an estimated arsenal of 290 warheads, France possesses the only European nuclear capability which exists beyond NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (and thus de facto American influence). But in reality, even the French nuclear programme depends to an extent on the U.S.

Macron’s proposal has received provisional support from several countries, specifically in the Baltic and Eastern European countries such as Poland where Tusk has stated that he “is talking seriously” with France about entering under their nuclear umbrella. However, there would be a mass of obstacles to overcome and significant domestic opposition to shared nuclear capabilities in France remains.

- Ramp up conventional deterrence: To avoid rapid escalation to use of nuclear weapons Europe must ramp up its conventional deterrence and offensive capabilities. This requires amongst other things mass rearmament and conscription, integrated and highly capable missile /drone air defence, and seamless border protection so as to make incursion by Russian forces costly and high risk. This would resolve the escalatory difficulties created by the chasm in respective conventional strengths. Accordingly, the SDR states that the “the UK must work with Allies to ensure NATO’s deterrence posture is fit for purpose across the spectrum of conflict, underpinned by collective investment in the range of capabilities necessary to deter nuclear use at any scale”.3 The EDA (European Defence Agency) has repeatedly highlighted gaps in the combat capabilities across EU and NATO states. Areas such as missile and air defences, high intensity preparedness and logistical support have all been of particular concern to the EDA.

Under western Cold War nuclear deterrence theory, it was popularly accepted that Soviet nuclear strikes could be deterred by the threat of total destruction of a high-density population centre such as Moscow and St Petersburg. After the declassification of Soviet military documents in the 1980s, intelligence analysts learnt that this was incorrect, and that in the case of an outbreak of conventional war in Europe with the Soviets, the USSR would have used what they classify as tactical nuclear and chemical weapons both early and aggressively.

Western Cold war theory was too “clean” and did not account psychologically for rational yet unreasonable actors (Cold War theory defined these as two nearly identical). Given that Putin has demonstrated these attributes in abundance, we must question whether Cold War assumptions apply. Would the loss of one city, or two or three, deter Putin from waging an epochal war on Europe, should he calculate that American commitment is limited? In order for the UK, or any other European power, to resume production of nuclear weapons, it would first have to withdraw from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, otherwise known as the NPT.

Created in 1968, the Treaty came into force in 1970 and has 191 signatories, including the United States, Russia, China and the UK. In contrast to treaties that prohibit or limit the use of conventional weapons, the NPT is seen as generally non-controversial, as demonstrated by the fact that it has more signatories than any other arms limitation treaty.

Although some non-nuclear powers have accused the NPT of solidifying the gap between the “haves and the have nots”, only North Korea has attempted to withdraw from the NPT via Article X. Article X sets out the process by which states are able to withdraw from the NPT, requiring them to provide an official notice – with evidence of “extraordinary events” that jeopardise their “supreme interests” – to all members of the treaty, the UN Security Council, and the UN Secretary General. There is no established consensus on the definition of either of the operative phrases above.

Whilst it is theoretically plausible that the UK could point to Russia’s increasingly belligerent stance on its NATO border, and a partial withdrawal of the American nuclear umbrella, as evidence of “extraordinary events” (3)

that endanger our “supreme interests”, leaving the NPT would inevitably be an extremely difficult political sell. This first hurdle would thus be a formidable early challenge to developing new nuclear weapons. This tension between legal obligations and the restoration of deterrence is present in the latest SDR, which proposes that “continued UK leadership within the NPT is imperative” in order to maintain the credibility of the NPT.(4)

Should the nuclear budget be separated from that of conventional defence? The MoD spends around 6-8% of the annual defence budget on the UK’s nuclear capabilities, encompassing the upkeep of warheads, maintaining delivery systems such as missiles and Vanguard class SSBNs, and building the new Dreadnought class SSBN. This is projected to rise as high as 10% in the 2030s, placing an even greater strain on the conventional budget. The NAO’s (National Audit Office) 2022 report detailed that “the Dreadnought programme remains a major pressure point” on total defence spending and that the nuclear budget consistently overruns allocated resources posing a threat to other equipment procurement plans.

The gap between a credible response with conventional weapons and the leap to the use of strategic nuclear weapons has led experts to warn about a “deterrence gap”. If the UK’s conventional forces are unequipped logistically or otherwise to respond to threats posed by global powers such as Russia and Iran, the threshold for using nuclear weapons to deter or punish may be lower.

In order for the UK to have sufficient deterrence, the UK must have a range of credible responses at different levels of escalation. The academic and military strategist Lawrence Freedman has long argued that without the ability to escalate proportionately, the UK faces a binary choice between a feeble response or employing a Trident strategic nuclear weapon, intended to be a weapon of last resort. If perceived to have insufficient transitional measures between conventional and full strategic nuclear response the UK deterrent is significantly weakened. As such, the cannibalisation of the conventional budget by the nuclear narrows the escalatory pathway further.

Given the serious repercussions of these financial challenges, one argument posits that the nuclear budget should be funded separately to the core conventional defence budget. This funding would come directly from the Treasury as part of a new “nuclear budget”, independent and ringfenced from other defence spending. Proponents of this idea point towards the fact that the nuclear deterrent is not a war fighting weapon, it is a wider national asset, serving purposes such as cementing the UK’s seat on the UN Security Council and other geopolitical goals. A key part of the reasoning for developing our own atom bomb after the war.

Policy Exchange in its 2020 paper “A Question of Deterrence”, advocated for “reevaluating the allocation of defence resources, including the consideration of separate funding mechanisms for the nuclear deterrent”.

It was argued this “could strengthen the UK’s overall defence posture by ensuring that conventional forces are not unduly compromised.”

Should US support for our deterrent be removed, how long can we maintain it? How much would it cost to go it alone?

The current UK Trident system is heavily reliant on the support of the US in terms of both hardware and infrastructure. Missiles in our system are leased from a pool of missiles based in the state of Georgia, we build our warheads based on data some of which is provided by US simulation tests, and we use many American components in our submarines. Whilst our system is operationally independent the use of US satellites, comms systems and test range facilities are beneficial and would have to be replicated.

In the short-term (0-5) years the system would remain fully operational.

However, as crucial components fail or age, without US support the system would become steadily more unsustainable. Without levels of investment not seen since the Polaris program in the 1960s, the UK deterrent would be at high risk of operational failure within 10-15 years.

Going it alone with an indigenous nuclear programme is not a novel idea. The V bomber force and later the Chevaline system were developed mostly independently but since then we have largely relied on US technological advancements primarily to reduce costs and counter the developing threats to strike certainty.

There are compelling strategic reasons for developing a home-grown nuclear deterrent. Without the US nuclear umbrella, the integrity of NATO’s Article 5 weakens as the range of potential responses to anti- NATO aggression shrinks. But these incentives do not come without severe financial and political challenges. A move such as restarting the development of nuclear weapon delivery systems at home would require cross-party consensus to ensure continued funding, and withdrawing from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), a highly controversial move.

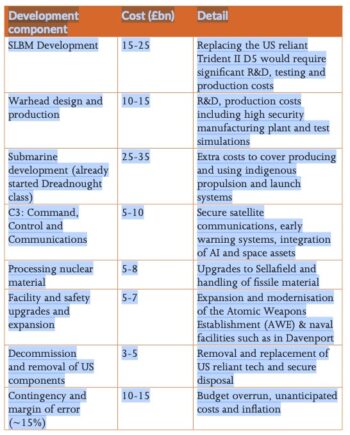

The cost of developing such a system at home is likely to be the most significant barrier. Development would likely take 15-25 years and could cost as much as £120 billion. The potential allocation of costs across development is likely to be:

Whilst these are the startup costs of the project, running costs are also a significant consideration. The estimated running cost per annum of an indigenous nuclear project is £3.1-3.7 billion, a 30-50% increase on the current Trident running costs of £2-2.3 billion a year. A useful comparison, France, spends roughly £4.4 billion a year on running costs for its fully sovereign nuclear programme.

Using current growth forecasts, over a 20-year spread a sovereign nuclear programme would commandeer around 0.35% of GDP annually.

Given the current UK defence budget hovers around 2.3% (with promises to increase it to 2.5 by April 2027), the government would need to increase it significantly to the region of 2.7% of GDP to account for the running costs of an independent nuclear programme. This of course does not account for the enormous front-loaded costs of onshoring development, infrastructure and servicing.

There exist a few policy solutions to reduce costs. For example closer collaboration with France in areas such as nuclear testing or the development of secure communications networks to share the financial burden. However, some key figures in French politics, are virulently opposed to such proposals, repeating that “the French nuclear deterrent must remain a French nuclear deterrent,” adding “it must not be shared, let alone delegated.”

Should we develop a non-strategic nuclear weapon?

The old debate on whether the UK should develop a non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) has had a topical resurgence since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Criteria on which to make such a decision are operational viability, geopolitical and treaty constraints, deterrence theory and alliance stability. Whilst the UK does have a credible strategic nuclear deterrent in the form of Trident, a growing number of defence strategists unsatisfied with current nuclear deterrence theory are exploring the impacts of developing a NSNW. In a region increasingly impacted by Russian nuclear chest-beating, the lack of a lower-yield NSNW with more flexible deployment options may be considered to degrade the UK’s overall nuclear deterrent posture.

The new SDR hints that the Government is now considering adding to its single-system nuclear deterrent, perhaps with air-launched non- strategic weapons. The document observes that the UK is “well-placed to lead Europe in enhancing its contribution to deterrence and assurance in the Euro-Atlantic”.5 This has been interpreted as a quiet commitment to purchasing jets which can be armed with tactical gravity bombs,6 the first time the UK possessed such a capability since it retired its V bombers.

Indeed, the SDR recommends that “more F-35s will be required over the next decade” –7 hinting at ongoing discussions over the procurement of F-35 As, which can carry gravity bombs.

The strategic case for expanding our nuclear arsenal is compelling.

Russia has a significant reported stockpile of 1000-2000 NSNWs. In contrast to UK nuclear doctrine, these weapons are not seen by Russian officials as part of a deterrent force but as a key part of their military doctrine for regular battlefield use. The Russian policy of “escalate to de- escalate” is reliant on a NATO response gap between limited responses and all-out strategic nuclear retaliation. The development of a NSNW would fill this much needed gap in the UK’s escalatory ladder.

This is not simply a question of developing tactical warheads, but the platforms from which to launch them. Currently, apart from the French who as discussed are not part of NATO’s NPG, NATO relies on American B61 bombs to deliver nuclear payloads from the air, which would become a vulnerability should America seek to withdraw even partially from the European security theatre.

This debate has been intensified by the MoD decision to push forward with the purchase of new U.S. produced F35, which would be the only plane in the UK arsenal capable of carrying the B61 nuclear warhead.

Although other European countries have raised concerns about a potential ‘kill-switch’ in the jet – allowing the U.S. to deactivate them unilaterally 5. Ibid., 99.

military chiefs in the UK are confident of operational independence, due to the UK’s status as a level one development partner for the F35.

Developing a sovereign UK NSNW would hedge against an American withdrawal, and when combined with French sovereign strategic nuclear weapons, would provide Europe with a range of sub-strategic capabilities to complicate Russia’s calculations.

Current NATO nuclear systems such as the B61 are also increasingly impacted by developments in anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems.

A modern mobile UK NSNW could address these gaps by being a more survivable option.

The development costs of a NSNW are estimated to be between £5-10 billion. But factors such as delivery system development and infrastructure upgrades mean development is financially significant. By potentially remodifying existing Trident designs the costs could be limited slightly.

Assuming general political will and support from regulators, development would take 7-10 years, alongside concurrent investment in and training for personnel and command centres.

I have hoped in this paper to throw some light on why and how the UK became a nuclear weapon state. The complex development of new weapons and delivery systems and pressures of cost.

The nuclear enterprise was always at the limit of our scientific, engineering and technical capability. In the 1950’s it was very much a national endeavour and needs to be that again.

Having been closely linked to the US in development of the first atomic bomb, which was a joint enterprise, costs have made it necessary for us to be intimately linked to America as delivery systems became more complex and sophisticated.

The US has proved itself to be a steadfast ally determined to render maximum assistance in the nuclear field when needed and there is no signal from any member of the Trump Administration of the intent to withdraw from the close links that already exist between our two SLBM forces or the nuclear shield from NATO Europe. However, as the U.S. launches a bottom-up audit of its global military and diplomatic commitments and the accompanying acute geopolitical uncertainty it would be foolhardy not to consider the unthinkable. This plus past difficulties with provision of the UK deterrent mean HMG should not shy away from the uncomfortable process of considering options should the worst come to pass.

- UK Ministry of Defence, Strategic Defence Review: Making Britain Safer: secure at home, strong abroad, 2025.

- The SDR, 98.

- Ibid., 99.

- Ibid., 100.

- SDR 99

- Harry Yorke and Tom Newton Dunn, British fighter jets to carry nuclear bombs. The

Times, 31 May 2025

-

The SDR, 115.

Admiral Rt Hon Lord West of Spithead GCB DSC PC is a Labour Peer in the House of Lords and a former Head of the Royal Navy. Admiral Lord West has spent the majority of his naval career at sea, serving in fourteen different ships and commanding three of them. He commanded the frigate HMS ARDENT in the Falkland Islands where she was sunk in their successful recapture.

He served three years as head of Naval Intelligence and three years as Chief of Defence Intelligence covering the Kosovo War. In November 2000 he became Commander-in-Chief Fleet, Nato Commander-in-Chief East Atlantic and Nato Commander Allied Naval Forces North.

Lord West served as First Sea Lord from September 2002 until 7 February 2006, covering the invasion of Iraq and widening of Afghanistan operations. As First Sea Lord he was responsible to the Prime Minister for the readiness, efficiency and security of the UK deterrent.

In July 2007, he became a government minister responsible for national security and counter-terrorism as well as cyber and Olympic security. He produced the nation’s first National Security and Cyber Security Strategies. He has been a member of the Intelligence and Security Committee since 2021.