By Edward Chan*

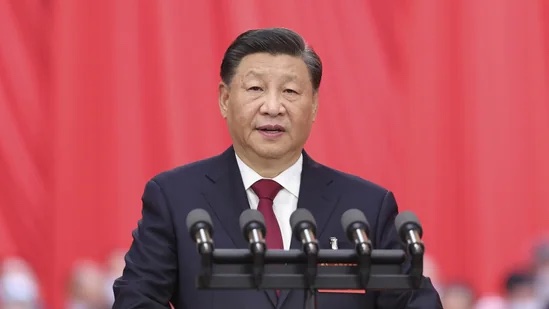

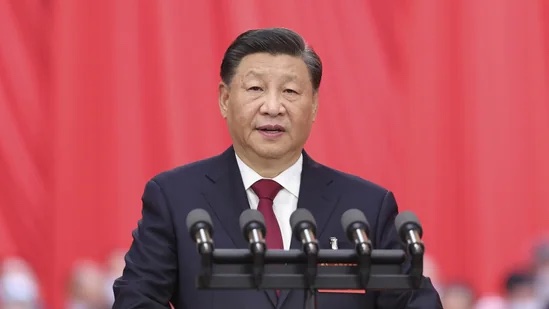

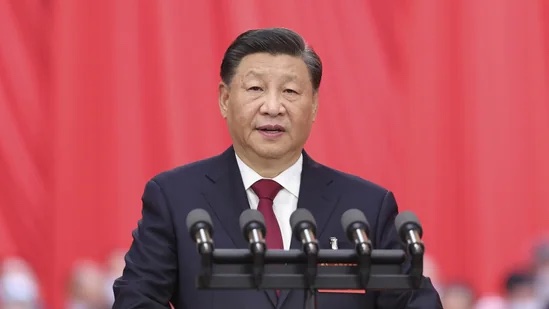

Since taking office in 2022, the Albanese government has stabilised Australia-China relations, with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese holding his third formal meeting with Xi Jinping at the G20 Summit. (The Australian Institute of International Affairs.)