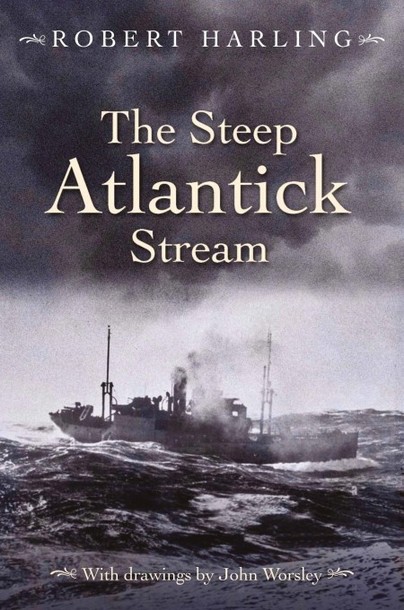

The Steep Atlantick Stream: A Memoir of Convoys and Corvettes. By Robert Harling. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, 2022; ISBN 978-1-3990-7288-5).

Reviewed by John Johnston

The Second World War continues to fascinate readers of books, viewers of television, and listeners to radio in a way that older and more recent conflicts do not. Perhaps the contrasts between good and evil, between justice and injustice, between morality and immorality are so sharp in the Second World War that no uncomfortable demands are made on the reader, the viewer, or the listener.

But perhaps too, those who told the stories of the Second World War were better wordsmiths than those who came before them or those who have come after them, and they carry the reader, the viewer, or the listener comfortably on a deep and flowing stream of consciousness rather than uncomfortably through a turgid swamp or across stones in the shallows. Robert Harling’s short and well-written memoir of his time as first lieutenant on the corvette, HMS Tobias, bears out those thoughts.

A peacetime yachtsman, Harling had volunteered for the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and seen action off Norway and Dunkirk and during the London Blitz, before travelling to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where Tobias was under construction. Made ready early in 1941, she escorted convoys through the waters of the North and the South Atlantic and took Harling from the sobriety of Belfast and Derry to the bleakness of Iceland and the exotica of Freetown. His time on board ended when, after a bout of pneumonia left him unfit for further service at sea, he was reassigned to intelligence duties in the Middle East.

As the Battle of the Atlantic was at its height during Harling’s time aboard Tobias, one might expect to be reading lengthy accounts of actions against U-boats and aircraft. One would be disappointed: such actions, when they occur, are short and confused affairs, the focus staying on the unremitting tedium of convoy escort duties, of watchkeeping on the high seas, and the unrelenting, ever-present sense of being hunted. Once, when he joined a motor torpedo boat raid on German convoys off the Dutch coast, Harling experienced the thrill of the hunt: yet one senses that he is in an alien environment and that his innermost sympathies are with the German crews he and the boat are attacking. Unsurprisingly, soon after this passage, he describes the shock of finding an abandoned life boat off the Irish coast and reflects on the traumas of conducting rescues on the high seas.

Such tales, however, are incidental to the main stories: the evolving relationship between the captain and his officers and between the officers and the crew, and the reactions of Harling and his shipmates to new climates, alien cultures, and different landscapes. Casual racism and social class merge into one another and into relationships on board. The bridge becomes a world in itself and so, whilst signalling ratings are known by name and trade, the engine room crew are a tribe of anonymous troglodytes, who serve only their leader, the chief engineer, WO Dundass, who in turn serves them in their dealings with the ship’s officers. Such seemingly rigid social divisions may seem alien and incomprehensible to us but as Harling notes, they were the skeleton which made the ship into a functioning organism and which gave a human scale to an otherwise unintelligible organisation.

Some months after Harling left her, Tobias was sunk with the loss of half the crew and all but two officers of her officers. Harling was then serving in Egypt: disconsolate and feeling out of place in the heat of Alexandria, he began writing the story of Tobias and the Atlantic cold. He continued working on the story through the remainder of the war, completing it after VJ-Day. As the story concludes, the balanced and pastoral prose of the text gives way to anguished melancholy and one realises that this is not a memoir but an agonised effort to overcome trauma, shock and sadness. Writing the story of Tobias must have been therapeutic, for after the war Harling had a successful and fulfilling career as a typographer, journalist, and editor.

Perhaps the contrast between Harling, the wartime naval officer and Harling, the peacetime editor of House and Garden is part of the continuing fascination with the Second World War. But enough philosophising: The Steep Atlantick stream is a jolly good yarn and just right for an early autumn evening.