Beijing has undertaken sweeping efforts to modernize its navy, China Power reports. At the 18th Party Congress in 2012, then-President Hu Jintao called for China to become a “maritime power” capable of safeguarding its maritime rights and interests. This position was reinforced in the 2015 defense white paper that declared the “traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests.”

This message was reiterated in April 2018 when President Xi Jinping suggested that “the task of building a powerful navy has never been as urgent as it is today.”

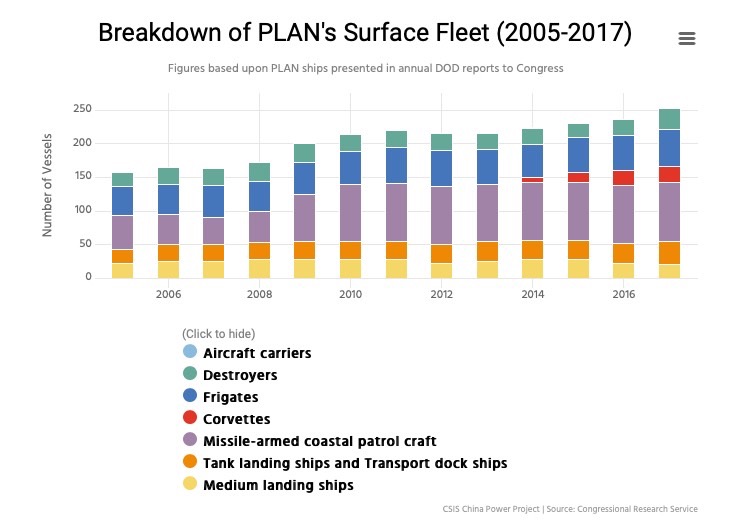

The modernization of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has resulted in a growth in fleet size and capabilities. Research conducted by RAND suggests that China’s surface fleet in 1996 consisted of 57 destroyers and frigates, but only three of these vessels carried short ranged surface-to-air missiles (SAM), making them virtually “defenseless against modern anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM).” Three quarters of its roughly 80 attack submarines belonged to the Soviet Romeo-class that entered service in the 1950s.

Over the last few decades, China’s navy has rapidly expanded. As of 2018, the Chinese Navy consists of over 300 ships, making it larger than the 287 vessels comprising the deployable battle force of US Navy.1 The fleet sizes of other leading nations are comparatively smaller. The British Royal Navy consists of 75 ships and the Royal Australian Navy has a fleet of 48 ships.

New ships are being put to sea at an impressive rate. Between 2014 and 2018, China launched more submarines, warships, amphibious vessels, and auxiliaries than the number of ships currently serving in the individual navies of Germany, India, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Eighteen ships were commissioned by China in 2016 alone and at least another 14 were added in 2017.2 By comparison, the US Navy commissioned 5 ships in 2016 and 8 ships in 2017. Should China continue to commission ships at a similar rate, it could have 430 surface ships and 100 submarines within the next 15 years.

According to the Department of Defense (DoD), a significant focus of the PLAN’s modernization is upgrading and “augmenting its littoral warfare capabilities, especially in the South China Sea and East China Sea.” In response to this need, China has ramped up production of Jiangdao-class (Type 056) corvettes. Since being first commissioned in 2013, more than 41 Type 056 corvettes had entered service by mid-2018.

The capabilities of the Chinese Navy are growing in other areas as well. RAND has reported that based on contemporary standards of ship production, over 70 percent of the PLAN fleet in 2017 was considered “modern,” up from less than 50 percent in 2010. China is also producing larger ships capable of accommodating advanced armaments and onboard systems. The Type 055 cruiser, for instance, is planned to enter service in 2019-20 and weighs roughly 5,000 tons more than the Type 052D destroyer that entered service in 2014. The Type 055 is slated to carry large cruise missiles and be capable of escorting an aircraft carrier into blue waters.

China is also leading the world in terms of the overall tonnage of ships it has put to sea. The collective tonnage of the ships launched by China between 2014-2018 was an impressive 678,000 tons — larger than the aggregate tonnages of the navies of India and France combined. Importantly, the PLAN’s total tonnage remains less than half that of the US navy, a gap estimated at roughly three million tons. This difference is largely attributed to the US fielding 11 aircraft carriers, each displacing approximately 100,000 tons.

Expanding Shipbuilding Capability

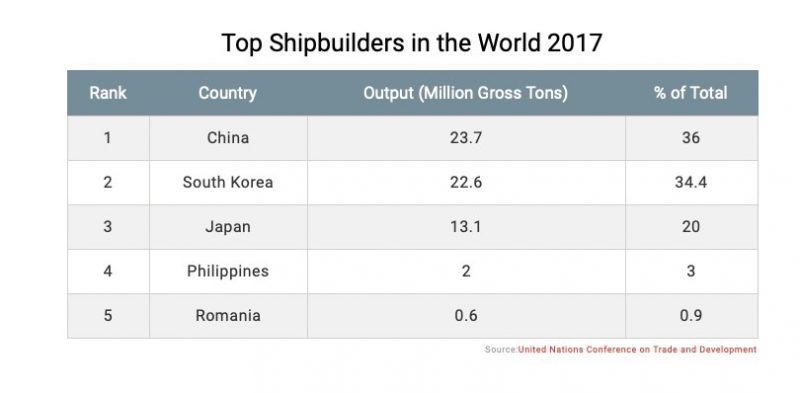

The rapid expansion of the PLAN has been undergirded by China’s growing shipbuilding capability. During mid-1990s, favorable market conditions and joint ventures with Japan and South Korea enabled China to upgrade its shipbuilding facilities and operational techniques. According to the DoD, the modernization and expansion of these shipyards has “increased China’s shipbuilding capacity and capability for all types of military projects, including submarines, surface combatants, naval aviation, and sealift assets.”

These advances have also facilitated China’s transition into a commercial shipbuilding superpower. Merchant shipbuilding production rose from just 1 million gross tons3 in 1996 to a high of 39 million gross tons in 2011, which was more than double the output of Japan in the same year. In 2018, China surpassed South Korea as the global leader in shipbuilding orders. Through the first 11 months of 2018, China’s shipbuilding industry captured an impressive 36.3 percent of the global market.

The same state-owned companies that dominate China’s commercial shipbuilding industry are also major players in the military space. China’s two largest shipbuilding companies — China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC) and China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) — are responsible for three quarters of China’s overall shipbuilding output. CSIC and CSSC have also produced all domestically built vessels recently introduced into the Chinese Navy.

There are six shipyards spread across China that fulfill the lion’s share of China’s naval shipbuilding needs – half of which are controlled by CSIC and the other half by CSSC. Each of these shipyards also contains facilities for producing commercial vessels. Jiangnan Shipyard (pictured), for example, is responsible for producing the Type 055 cruiser and it is rumored to be the location where Beijing’s third aircraft carrier is under construction. The shipyard also delivered one of the world’s largest ethane and ethylene-capable tankers, the Navigator Aurora, in 2016 and the Xue Long 2 icebreaker in 2018.

Jiangnan Shipyard plays a vital role in the PLAN’s modernization. To provide more insight, CSIS has conducted detailed imagery analysis that tracks how the shipyard’s infrastructure has expanded and traces the naval activity at Jiangnan in 2018.

High levels of integration between military and commercial shipbuilding is relatively uncommon. In Europe, shipbuilding operations have focused in on consolidating and expanding military activities instead of integrating merchant and military shipbuilding operations. Similarly, major military shipbuilders in the US – such as Huntington Ingalls Industries (responsible for Gerald R. Ford-class supercarriers and nuclear-powered submarines) and General Dynamics Electric Boat (the only other builder of nuclear-powered submarines for the US Navy) – focus almost exclusively on defense contracts.

The operational standards and technical requirements of naval shipbuilding differ from that of the commercial sector, which has the potential to affect the productivity and efficiency of both activities. Nevertheless, China’s State Council has explicitly encouraged this practice in hopes of boosting technology transfers among sectors. A 2013 plan released by the State Council called on domestic shipbuilders to “breach military industry capacity-building bottlenecks in key products, materials, manufacturing equipment” by “rely[ing] on major civilian research projects.”

Republished with permission of China Power