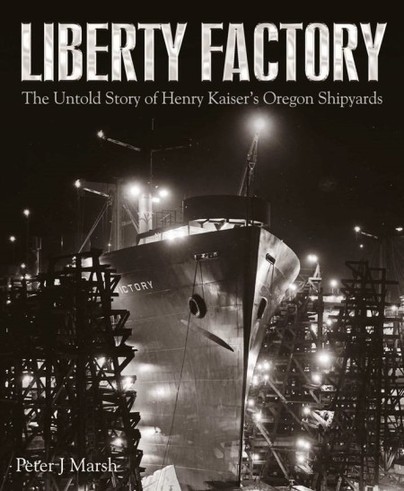

Liberty Factory; The untold story of Henry Kaiser’s Oregon shipyards. By Peter J March. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, 2021.

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

Liberty Factory by Peter J March, a British expatriate resident in the Portland region, is a history of the area’s wartime shipyards which made a substantial contribution to US maritime production in World War Two.

The war emergency shipbuilding capacity in the Portland area comprised three shipyards established by the industrialist Henry J. Kaiser and three smaller yards. The Kaiser yards were the Oregon Shipyard (OSC), Kaiser Swan Island and Kaiser Vancouver located on the Colombia and Willamette Rivers. OSC built 322 Liberty standard war emergency freighters and 99 of the later improved Victory ship, as well as 33 Attack Transports. Swan Island specialised in the standard T2 tanker of which 147 examples were constructed. Kaiser Vancouver built over 100 ships of five different types, the most noteworthy being 50 escort aircraft carriers (CVE), several of which were transferred to the Royal Navy.

President Franklin D Roosevelt’s ‘Arsenal of Democracy’ radio speech of 29 December 1940 awoke America’s vast industrial potential for the looming world war, initially to re-equip its own forces and to indirectly support Britain through air and maritime production against an isolationist mood in the US. Pearl Harbor changed all that and how the Portland industries met the challenge is the centrepiece of this book.

US industrial capabilities were based on a group of extraordinary industrialists of which Henry J Kaiser was an exemplar. He played a leading role in coordinating six large corporations in the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam in the 1930s, an example of President Roosevelt’s New Deal to combat the Depression. Although without shipbuilding experience, Kaiser instigated a new concept in shipbuilding, with the encouragement of the US Government. Stemming from a British requirement for the mass construction of standardised war emergency freighters, Kaiser began building Liberty ships at the greenfield OSC site, soon to be followed by Kaiser Swan Island and Kaiser Vancouver (collectively known as Vanport).

The Liberty ship construction time was drastically reduced as production ramped up. The keel of the first Liberty, the Star of Oregon, was laid on 19 March 1941 and was launched on 27 September, 45% complete. By the time OSC cut over to the Victory ship, Libertys were taking only 40 days to build. The most famous example of Liberty building was the Joseph N Teal, built in 10 days. Launched in the presence of President Roosevelt it was a highly stage-managed example of American industrial innovation and was a huge morale-booster and publicity event.

The other three Portland area shipyards were the Commercial Iron Works which built Landing Craft Infantry (LCI), PCs (subchasers) and outfitted CVEs, the Albina Engine and Machine Works (PCs and LCIs) and Willamette Iron and Steel which built escort patrol craft (PCE) and Yard Minesweepers (YMS), many of which went to the Royal Navy. The significance of the Portland output of small ships and CVEs to the RN was the firm and affectionate relationships established between the American workers and the RN personnel.

Liberty factory is more than a study of wartime shipbuilding; it is a social commentary and overview of contemporary labour and community life. This includes the recruitment of largely unskilled labour, requiring accelerated training to fill roles previously needing years of apprenticeship. Not least was the hiring of women for shipyard and workshop trades roles, initially opposed by conservatives, but the women’s adaptability and dexterity soon proved the critics wrong. Vast new housing estates had to be constructed for the thousands of workers brought into the Portland area. Kaiser pioneered worker facilities on the Grand Coulee Dam project and brought these initiatives to Vanport. He established advanced medical facilities and health plans for the workers, 24-hour canteens, worker housing and even a 24-hour child-care facility.

However, all was not entirely tension-free; black workers suffered under the racial attitudes of the time, being allocated the most demeaning employment. Absenteeism was a major problem, not only to Vanport but the entire US wartime industry. Shipyard workers received high pay, but the demanding and arduous work tempted many to shirk their responsibilities. There were innovative ways of combatting absenteeism by shaming recalcitrants and promoting ‘presenteeism’ (a word invented by Kaiser). Large placards shaming slackers and comparing time lost to the number of ships that could have been built in that time were examples of these campaigns (OSC calculated four Liberty ships).

Peter Marsh, through his British origins, brings an objective view to his topic without histrionics. However, he highlights the American talent for publicity and promoting competition between rival industrial entities for the government-awarded ‘E’ for Excellence and other flags and stars to spur on workers.

The book is splendidly complemented by dramatic, large-scale black and white photographs of the shipyards in action. Few would argue that, of all industrial enterprises, shipyards and their associated workshops are the most photogenic. Change of shift times with thousands of tired and grimy men and women workers filing out the gates allow us to sense the look of dedication and determination to accomplish their mission. That many of the workers were women and men over 45 shows the workforce demographic. One similarity to today’s commuting woes were the traffic jams exiting the huge carparks at shift changes. Vanport was situated away from established public transport lines and, despite Kaiser providing buses, cars prevailed even against tyre and petrol rationing.

The wealth of technical, industrial, entrepreneurship, labour and social history, together with the excellent photographic record makes Liberty Factory a fitting tribute to the workers of Portland’s role in the Arsenal of Democracy’ of a time now passed. Nothing remains of these vast industrial estates. Impressive though Vanport and the neighbouring shipyards’ outputs were, this was only a fraction of US wartime shipbuilding (a total of 2710 Liberty ships and 414 Victory ships were built in US yards).

Some might say that all wartime workers experienced the hardships of relentless production pressures and that the Vanport people earned good money while safe from enemy attack, unlike British workers. Nevertheless, it was precisely these circumstances which provided the war-winning output in support of all the allied nations.

Anglo-American relations were mentioned above and Peter Marsh provides us with this charming anecdote, indicative of the mutual feelings at the time: Phyllis Dunnuck, an accounts clerk at Willamette Iron and Steel Corporation, began to follow the exploits of RAF Wing Commander JE (Johnny) Johnson through media reports. Following a report of Johnson’s 38th air victory, mention of him appeared to have ceased. Concerned at this, Phyllis wrote to the Queen, stating in her letter that: ‘to many of us Johnny Johnson has assumed a personality allied with the boys of our own families who are now overseas. It is with heartfelt concern that we enquire of his safety and further progress since last September’. Phyllis goes on to say: ‘Perhaps it would be of interest to you to know that we are employees of Willamette Iron and Steel Corporation, a firm that has constructed a number of vessels for the British Royal Navy’. We are grateful to have had a share in this program and in the knowledge that we have helped in a small way to further our common cause. With best wishes for you and your family and a quick and successful end to the war…’

The reply from Buckingham Palace, dated 20th March 1945, was signed by Wing Commander Peter Townsend, Equerry-in-Waiting:

Dear Miss Dunnuck

I am commanded by Her Majesty the Queen to write and thank you for your kind enquiry about Wing Commander J.E. Johnson, DSO, DFC. This Officer has held an appointment on the staff of Wing Headquarters of the Second Tactical Air Force since July 1944 and, as far as is known, is in the best of health.

Her Majesty commands me to say how touched she is to hear of your concern at the welfare of so distinguished an Englishman, and that you feel his personality has so much in common with your own fighting men, our allies. Her Majesty is proud to learn that you and your co-workers at the Willamette Iron and Steel Corporation have shared so importantly in the ubiquitous victories of the Royal Navy which, now alone, now in concert with the United States Navy, has consistently outmatched our enemies.

The Queen is grateful for your kind wishes for the Royal Family and joins with you in praying that an early victory may, by continuous effort, develop into a strong and lasting peace’.

Peter Marsh notes in parenthesis that this is the same Peter Townsend who had the unfortunate later relationship with Princess Margaret.

For those who wish to explore the genesis of the Liberty ship beyond Vanport, John Henshaw’s ‘Liberty’s Provenance; the Evolution of the Liberty Ship from its Sunderland Origins’, published by Seaforth and reviewed previously in these columns, is an excellent source.

In summary it is hard to fault Liberty Factory. It is a fine technical, social and human story of wartime endurance and dedication which extended beyond Vanport to workers of all the allied nations.

Liberty Factory is most highly recommended.