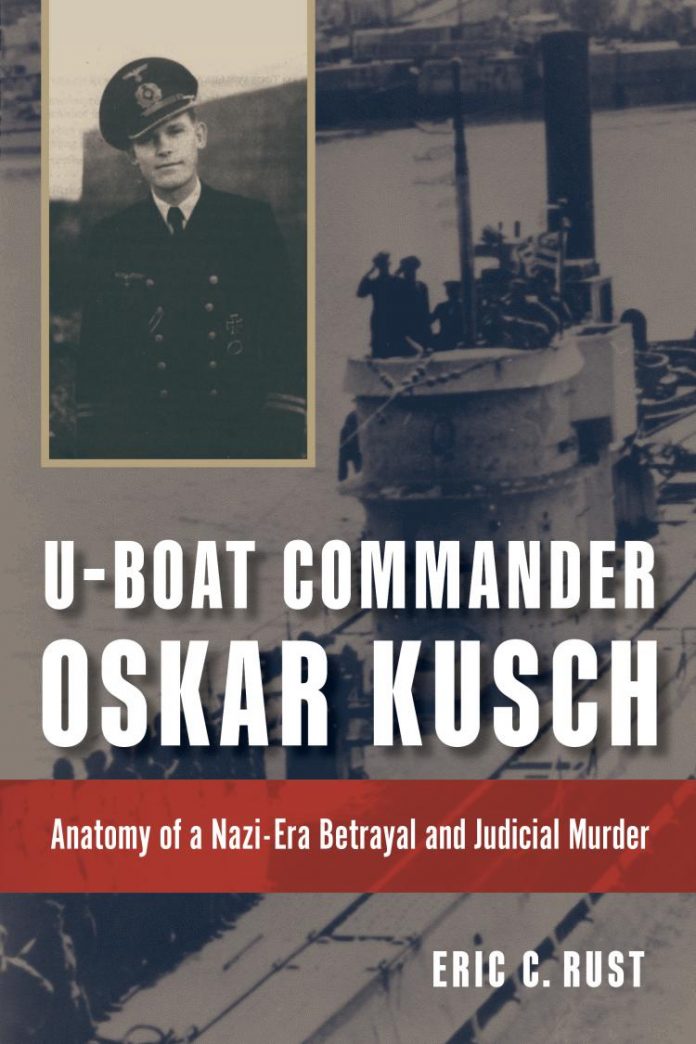

U-Boat Commander Oskar Kusch; Anatomy of a Nazi-era betrayal and judicial murder. By Eric C Rust. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2020.

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

This is the story of Lieutenant Oskar Kusch, a brave and talented U-boat commander who was tried and executed in May 1944 for defeatism and defamation of the ruling Nazi clique.

Many of the post-World War 2 generations are of the general impression that the Third Reich military forces, sworn as they were to Adolf Hitler personally, ruthlessly pursued the Reich’s warped aims to the death. This was certainly true as the war turned against Germany from 1943 to the unconditional surrender of the regime in May 1945. However, not all German military personnel shared Nazi fanaticism but sought to carry out their duties honourably without compromising their personal moral and philosophical standards.

One such individual was Oskar Kusch. Born in 1918 to a liberally minded family, his early years were spent in enjoying companionship in trekking, camping and philosophical free-thinking discussion in literature and art in the short-lived period of Weimar Republic democratic and liberal republicanism.

National Socialism’s rise to power in 1933 saw, for German youth, conscription into the Hitler Youth and associated party organisations. Kusch and his friends distanced themselves from a political philosophy they found contrary to their natures but realised that their lives would be overtaken by the abhorrent absolutism of National Socialism.

Kusch realised his boyhood dream when he entered the navy in 1937. He excelled as a midshipman, undertaking peacetime training cruises to foreign ports, opening his mind to external influences and cultures. Following the disgrace of the High Seas Fleet mutinies of 1917/18, which influenced the collapse of Germany into defeat and civil war, the post-war German navy was a reconstituted force determined to restore its reputation with a professional and highly competent officer corps. Oskar Kusch revelled in his naval training and emerged as a talented and respected officer.

The emergent U-boat arm was the Kreigsmarine’s elite force, as it had been in World War One. The stain of mutiny had not spread to the U-boats in 1918 and submarine warfare was the most effective maritime threat against Britain and allies. Little wonder that the best officers gravitated to U-boats to wreak havoc during the two ‘happy times’ in the North Atlantic and off the US east coast in 1940 and early 1942 respectively, winning promotions and decorations.

Oscar Kusch was posted as a watch officer to U-103 in which he distinguished himself professionally and won admiration from all on board. However, his liberal political outlook began to emerge in the close confines of the U-boat. The pre-war permanent navy officers scrupulously avoided voicing overt political opinions; however, as the war progressed, Nazi-imbued reserve officers and midshipmen were drafted to U-boats, their now-shortened training regimes adding to a changed environment of heightened political suspicion.

Appointed in command of U-154, Kusch undertook two patrols; the first of which in Spring 1943, was successful, sinking one ship and damaging two others off Brazil. His second patrol in the same waters accomplished little due largely to the sophisticated allied anti-submarine capabilities which were beginning to turn the tide in the Battle of the Atlantic. It was on this patrol that Kusch became more unguarded in his discussions with his officers, who included a nazified trio, the senior of which was Lieutenant Ulrich Abel.

Abel, an outwardly well-qualified mariner, had served in the German merchant marine and was a lawyer. He had been called from the reserve to distinguish himself in command of a minesweeper for which he was decorated. Unlike the pre-war navy, the merchant marine was extensively nazified and Abel, together with the U-boat engineer Kurt Druschel and junior watch officer Arno Funke seethed with resentment as Kusch (illegally) monitored allied radio broadcasts, (correctly) assessed allied strengths and warned of Germany’s inevitable defeat in the hands of the criminal Nazi leadership. Kusch’s anglophile outlook was demonstrated by frequent outbursts in English, which the crew appreciated as a humorous and endearing aspect of their eccentric commander.

For U-154’s second patrol a Wehrmacht medical officer, Dr Hans Northdurft was attached as a supernumerary to study U-boat crews in action. Northdurft joined the other three as a self-appointed counsellor to mitigate Kusch’s behaviour. Abel’s antagonism against Kusch climaxed on return from the patrol; having been posted to a U-boat commander’s course, Abel submitted a complaint to his immediate superior, the training division commander, rather than the line U-boat command, stating ‘how Kusch offered repeated and unmistakeable indications of being strongly opposed to Germany’s political and military leadership. I therefore consider him unfit to serve as a U-boat commander.’

Originally intending his complaint to result in Kusch’s removal from U-boat command, in fact it led to a trial culminating in execution. Kusch’s arrest and trial shocked the U-boat arm; Abel’s report submission to a training command rather that the line staff was considered unpardonable by his combatant comrades and may have mitigated repercussions on Kusch had Abel followed correct procedure through the chain of command. In the resultant trial the prosecutor sought a 10-year imprisonment; however, the presiding judge Karl-Heinrich Hageman, seeking to make an example of Kusch, imposed the death penalty.

The author Eric Rust, a former Bundesmarine officer, is a history academic specialising in German maritime and naval history, especially submarine warfare. In writing this book, Rust brought his expertise in German naval law, procedures and conditions of life in the U-boat arms and the wider Third Reich to a most absorbing and tragic story. The Kusch case reverberated well beyond his May 1944 execution – extending over half a century as the later lives and fates of the survivors are recounted. Grand Admiral Doenitz, the U-boat commander, despite his perceived reputation of championing his personnel, is shown as a callow Nazi who spurned reasoned pleas for mercy on Kusch’s behalf. Doenitz’s excuse was that remitting the death sentence would endanger U-boat morale, even though the submarine crews remained steadfast to the end, as they had done in the First World War.

Oscar Kusch lost his life to tyranny, but his spirit of honesty, principal and courage lives on in this superb book which is most highly recommended.