The Last Post has been played for these men and women in services all over Australia. They lived for seventy years after the allied victories in Europe and the Pacific in 1945 which they helped to secure. The lived seventy years longer than their young friends who died in war and lie far from Australia.

Veterans who saw service overseas during the Second World War are now in their nineties and inevitably we will see all of them disappear from our commemorative services within a decade.

We respect and cherish those who are with us, we salute their service, and wish them good health and happiness.

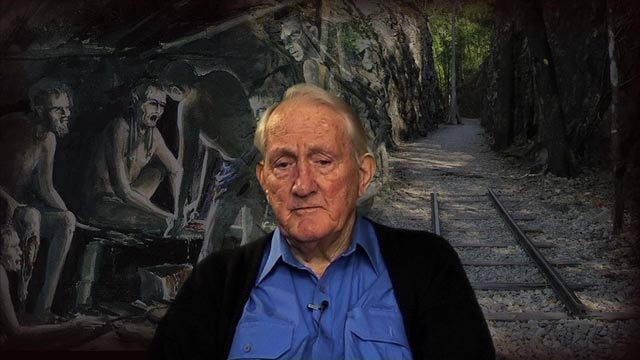

Witnessing these valiant Australians fighting up a ridge under machine-gun fire marked Tom for life. He never forgot what he saw.

After surviving the horror of the Thai-Burma railway as a Prisoner of War he was taken to Japan where he worked as a slave labourer in a mine smelting lead and copper alongside ordinary Japanese workers. There he learned that he hated militarism not the Japanese people.

Later in life he often quoted Martin Luther King’s statement that:

“Hate distorts the personality and scars the soul. It is more injurious to the hater than the hated.”

In 1960, he revisited Japan as part of a peace initiative.

PAUSE

Last December a much less well known veteran died. He was the very last RAN officer to have survived the sinking of the Australian cruiser HMAS Perth. His name was Gavin Campbell. (The eulogy delivered at his funeral by Mike Carlton is here.

In 1942 Sub Lieutenant Gavin Campbell, was a lanky young officer from Portland in Victoria. He was the secretary to Perth’s Captain Hec Waller. Between air raids on Batavia, (now known as Jakarta), he celebrated his 21st birthday in Perth with his brother officers and his captain. Another guest was Lieutenant Commander Robert Rankin, captain of the sloop HMAS Yarra, which was berthed near Perth.

Both Captains, Waller and Rankin, were soon to be killed in action, on the bridges of their ships, in command, fighting back against what now seems hopeless, overpowering odds.

After the birthday celebration Perth sailed to join an allied force of Dutch, British and American cruisers and destroyers off East Java, in what was a gallant but futile attempt to turn back a Japanese invasion force.

At the Battle of the Java Sea, on the night of February 27, that Allied squadron was badly mauled and beaten. Two Dutch cruisers and three Allied destroyers were sunk by torpedoes.

Perth survived that battle, but was low on ammunition, and the next day she was ordered to flee the advancing Japanese, to head south for Australia, to fight another day. But on that night the 28th of February, she and the American cruiser USS Houston were engaged by Japanese destroyers in the Sunda Strait, between the islands of Java and Sumatra.

Captain Waller and his crew fought courageously, as did Houston, but it was far from an even fight. Perth was struck by three torpedoes and a blizzard of gunfire, and left shattered and sinking. Waller ordered his men to abandon ship moments before he was killed on his bridge.

Gavin left his action station and was perched on the guard rail and about to jump when the fourth and final torpedo hit the ship and blew him high into the air and dropped him into sea. Luckily, he was wearing his life jacket, his Mae West, and when he came-to in the water it held him up.

But as he tried to swim, he found he had a broken leg, trailing behind him. The pain was excruciating, but he hauled himself onto a raft and there Able Seaman Bob Collins used his knife to hack off some strips of wood from a floating packing case and splinted the leg as best he could.

It was the first of countless acts of mateship given and received by these Perth sailors in the months and years ahead, and it saved Gavin’s leg and his life.

But his ordeal had just begun. When they eventually staggered ashore on Java, Gavin – barely able to move –he found himself on a beach with another wounded sailor, Able Seaman Denny Maher from Sydney.

“We can’t just stay here,” Gavin told him. “We’ve got to move on or we’ll die.” So for three weeks these men staggered down the coast of Java, in the burning tropical heat of March. Gavin was wracked with waves of pain, limping and hobbling. They were tormented by hunger and thirst. Sometimes villagers gave them a handful of rice.

There were some days when Gavin simply couldn’t move at all but Able Seaman Denny Maher stuck with him. They encouraged each other, and they went on, unbeatable, indomitable, until eventually they entered a small town, where a local nurse took them in, and bathed their wounds and fed them. They intended to escape from Java by sea but the Japanese arrived the next day to take them prisoner.

For Gavin and Perth’s survivors capture was the beginning of three agonising years of cruelty and savagery as a prisoners-of-war on the Thai Burma- Railway. Men worked until they were skeletons, bashed or shot by their guards if they could not continue to labour.

Gavin came down with Beri Beri, a disease caused by starvation and vitamin deficiency. Untreated, it’s fatal. He was nursed back to health by an Australian doctor, Albert Coates, and a Dutch chemist, also a prisoner, who had developed a vitamin injection from some local fruit.

There were 681 men in Perth’s ship’s company the night she sank. Only 328 of them survived the battle. 106 of them died as prisoners of the Japanese. Less than a third of her ship’s company, 218 men, lived to return to Australia.

Gavin endured the endless agony of those three years as a PoW with the strength and courage and unbreakable spirit that were the hallmarks of his life.

In 1945, in the last days of the war, it was Gavin’s turn to give mateship. The Japanese marched the sick men to a new camp outside Bangkok. Another of Perth’s officers Lieutenant Lloyd Burgess, was too weak to make it on his own. Gavin carried him most of the way, through the jungle limping along on his healed leg. That saved Lloyd Burgess’s life. Both of them lived and made it back to Australia.

Gavin was liberated in Thailand when a British commando appeared from out of the jungle and it was all over. He arrived at Melbourne’s airport on a chilly November day. There was no one there to meet him, so he went over to a Red Cross Hut and explained to the lady there that he’d just returned from being a prisoner of war of the Japanese.

“Well,” she said. “I suppose you’d like a cup of tea then.”

Gavin served on in the Navy post war. Like Tom Uren he was a man who did not hate. He had seen so much violence and killing, cruelty and horror, sickness and death – so much of man’s inhumanity to man – that he would not be party to its continuation.

Gavin’s long life was one of service to his family and support for friends and loyalty to the Navy he had served so well under the most difficult circumstances.

Our remembrance of this heroic generation, now passing into history, is important so last December a new bronze statue was unveiled by the Chief of Navy in Melbourne outside the former RAN recruiting depot, HMAS Lonsdale. It is called “Answering the Call.” It shows a young Second World War sailor with his kitbag.

This figure represents all RAN officers and sailors who fought the war at sea in 1939 to 45. He also represents the other two naval services, the Womens’ Royal Australian Naval Service, who were the Navy’s essential support ashore, and the RAN Nursing Service whose devotion to duty was, as always, ‘beyond praise.’

In the six years of that war the RAN Volunteer Reserve expanded from 4400 officers and sailors to over 30,000 men and women.

Appropriately our newly qualified bronze sailor is looking out at the entry to Port Philip Bay. Behind him is the training depot. Ahead is the open sea – his new home where he must brave what the naval prayer accurately calls “the dangers of the sea and the violence of the enemy.”

In the first years of the war many of our RAN ships both large and small did not survive the battles in which they were engaged. Ships companies fought to the end often against heavy odds, many complemented by Royal Navy personnel who served in Australian ships, as RAN personnel were made available for service with the Royal Navy.

In the Second World War 219 officers and 1951 sailors of the RAN lost their lives. Most lie with their ships and have no grave but the cruel sea.

So when one considers what new recruit sailors who “answered the call” were facing when they joined their first ships, one can only admire the mental strength, resilience and the enduring courage that these very young men displayed.

While remembering the RAN’s sailors we should not forget the thousands of seamen of the Australian Merchant Navy who served the allied cause, and the hundreds who died and were wounded, in both world wars. It was Merchant Navy ships, sailing under the Red Ensign, which carried the sinews of war, food, fuel, ammunition, troops and tanks, to the battlefronts of the world. They also sustained the populations at home until victory was won.

The memorials that are the backdrop to our commemorations across the nation remind us of all those who lie far from here. They called this town and this district home. But our memorials also remind us of those who returned and lived out their lives as hard working Australians who married, built new families and modern Australia.

These were great hearted men like Tom Uren and Gavin Campbell and tens of thousands of others, men and women, who served Australia in peace as they had defended it in war. We are all their heirs and we are in their debt. Their legacy to us is our life long liberty.

For many of us, those who came home from war were our parents and grandparents. We knew them and loved them all our lives. Every year on Anzac Day they remembered their friends who never came home.

We are here for them all.

The wreathes we lay, the Last Post we play, and the minute’s silence are for them all.

LEST WE FORGET