Churchill and Fisher: Titans of the Admiralty. By Barry Gough. Seaforth Publishing, Barnsley, 2017.

Reviewed by Tim Coyle

‘TWO very strong and clever men, one (Fisher) old, wily and of vast experience, one (Churchill) young, self-assertive with great self-satisfaction but unstable. They cannot work together; they cannot both run the show’. So wrote Rear Admiral Sir David Beatty in December 1914 of the two ‘titans of the Admiralty’ – so disparate in ages but so similar in an obsessive desire for power, single-mindedness in achieving it and destined for disaster in the political maelstrom of the First World War.

The very title ‘Churchill and Fisher at the Admiralty’ quickens the pulse of the student of modern history as it exposes the breathless dramas within the British government and specifically the administration of the mighty Royal Navy in the first two years of the Great War by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, and his political master First Lord Winston Churchill. The author, Barry Gough, is a multi-credited Fellow of King’s College, London and Archives Fellow of Churchill College Cambridge. His works on sea power and imperial affairs includes an intimate study of two of the greatest historians of the Royal Navy, Arthur Marder and Stephen Roskill, in Historical Dreadnoughts, reviewed previously in these columns.

In his ‘A Note on Sources’ Gough explains his approach to the huge store of primary and secondary resources and writings of both Fisher and Churchill, their biographers and archivists. He states; ‘The conscientious historian is faced with many difficulties in determining the reliability and disinterestedness of the sources available. For a book like this, unique challenges present themselves. Chief among them is the fact that Fisher and Churchill were quite capable of using history to their own ends. Both were masters of the English language and the alluring turn of phrase that carried a sense of conviction. Their artful language reflects their personalities and characters’.

Gough’s Notes look beyond Fisher’s colourful and incendiary letters to reveal a deep and complex individual. The deeper analysis is aided by commentaries by third persons close to Fisher, such as Whitehall insiders Lord Esher and Maurice Hankey. Fisher’s two published works are less memoirs than ‘rough fragments of autobiography, a stringing together of literary snippets’ according to Gough. Fisher had no capacity to formulate and expound an evaluation of British naval power and statecraft.

Fisher’s well-known reforms are discussed in detail: the Selbourne scheme for officer education, the raising of the status of engineering officers, the mass disposal of ineffective ships ‘that could neither fight nor run away’ and his crowning achievement, the Dreadnought all-big gun battleship and its running mate, the more lightly armoured and fast – but flawed – battlecruiser. During Fisher’s first period as First Sea Lord from 1904 to 1910 the Royal Navy was split between those ‘in the fishpond’ and those opposed to the reforms, led by Admiral Lord Charles Beresford.

First Lord Winston Churchill engineered Fisher’s return as First Sea Lord in October 1914 to replace Prince Louis Battenberg, rendered ineffective by a malevolent and unfounded whispering campaign over his alleged German connections. Churchill needed a man of action to work with him to defeat the German navy in a second Trafalgar or by asymmetrical application of seapower to strike the enemy from unexpected directions. Fisher’s self-impressed mandate was that he was the man to win the war. He had little regard for the British Army which he famously stated was ‘a projectile to be fired by the navy’ and resented Lord Kitchener’s status as Secretary of State for War. In his first period as First Sea Lord Fisher had materially equipped the Royal Navy in the form of revolutionary armoured ships, had streamlined officer training, disposed of obsolete ships and reduced his opponents, not in the ‘fishpond’, to ineffectiveness. The RN was in all respects ready to challenge and defeat the upstart Imperial German Navy – a service without tradition and a creature of Admiral Tirpitz and his overlord Kaiser Wilhelm – expectantly delivering to the British public a second Trafalgar.

With his return to the Admiralty in 1914 Fisher identified German submarines and mines as emergent threats to the fleet while increased acquisition of these weapons systems were a force multiplier for the RN. But his driving ambition was to equip and mount a naval and military assault in the Baltic, rounding on the German navy in its bases and striking towards Berlin thus circumventing the stalemate of the western front trenches and shortening the war. Fisher never wholeheartedly supported the Dardanelles campaign which was to be his, and Churchill’s downfall.

Winston Churchill has arguably one of the most extensive biographies and bibliographies of any world leader not the least of which were Churchill’s own writings such as the five volume ‘The World Crisis’ covering the First World War. In ‘The World Crisis’ Churchill was able to manipulate the record to divert criticism, particularly as regards his role in the Dardanelles fiasco. Churchill exhilarated in the role of First Lord. An admitted ‘war-lover’ he initially relished his association with Fisher. Churchill’s innovations included the raising of the Royal Naval Division, formed with undertrained hostilities only personnel, who could not be used at sea and who were flung against the invading German forces in Belgium in the early weeks of the war. Churchill vain-gloriously rushed to Antwerp and unilaterally took command of the British and Belgium forces. So enthused by the prospect of military glory he telegrammed Prime Minister Asquith offering to resign as First Lord, be given military rank and appointed as field commander. Asquith sensibly rejected this melodramatic intervention and ordered him home.

Churchill shared with Fisher a fascination for innovative campaigns and so the prize of seizing the Dardanelles, capturing Constantinople and forcing Turkey out of the war, formed and grew in Churchill’s fertile mind. This campaign, so integral to Australian military lore, continues to fascinate and horrify a century later. Churchill believed the Dardanelles could be forced ‘by ships alone’ using obsolete battleships. Fisher wanted military supplementation which Kitchener initially refused. The subsequent failure of the March 18 1915 naval attack and the belated land campaign, begun on 25 April, so disgusted Fisher that he abandoned his post as First Sea Lord in May and decamped to the countryside despite the prime minister ordering him to return ‘in the king’s name’.

The agonies, machinations and repercussions of the Dardanelles Commission saw Fisher and Churchill banished to the political wilderness. Both seethed at being out of power: Fisher was appointed to head the Board of Invention and Research, a frustratingly marginal organisation beset with political encumbrances which was eventually disbanded. Churchill went to the Western front as a lieutenant –colonel before returning to become Minister of Munitions though dogged for years until his return to the Admiralty in 1940 (and then as prime minister) by the Dardanelles failure.

Fisher and Churchill’s greatest contribution to the war at sea was Fisher’s materiel and administrative reforms implemented largely during his 1904-10 period as First Sea Lord, and Churchill’s ensuring the Grand Fleet was at its war stations on 04 August 1914. However, neither Fisher nor Churchill were invited to be present at the surrender of the German High Sea Fleet in 1919. Fisher, by then a spent force and regarded as mentally unhinged, died in 1920; despite his latter-day political banishment he was lauded as the greatest admiral since Nelson at his funeral. Churchill gained his redemption in the Second World War.

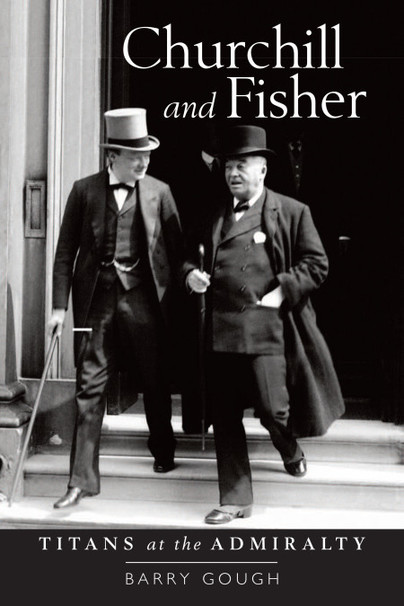

The book’s jacket illustration sums up the initial rapport between the young, ambitious politician and the elderly naval genius. It candidly depicts Fisher and Churchill emerging from the Committee for Imperial Defence building in Whitehall. Both top-hatted and impeccably dressed, Fisher strides ahead, overcoat thrown open, left hand in jacket pocket, right hand grasping a swagger stick. His mouth is open, doubtless pontificating to an admiring Churchill whose head is turned towards Fisher; eyes glinting and seemingly hanging on every word.

This is a most enthralling story, well told by Barry Gough. He has distilled and weighed the rancour, political intrigue, strategic and operational challenges and the (mostly) dismal record of the war at sea up to Jutland. The well-known politicians and admirals return to life with all their proclivities – admirable and less so. Gough gives us a fresh interpretation of these portentous times which build on the writings of previous generations of historians and naval commentators. It is a book to be valued as a standard treatise of the times for students of the period – whether they are in the ‘fishpond’ or not.