Honour denied: book on Teddy Sheean launched

FOR many years a story of how the Royal Australian Navy badly treated the commander of HMAS Armidale after his ship was sunk has been promulgated. But it now seems this is not true.

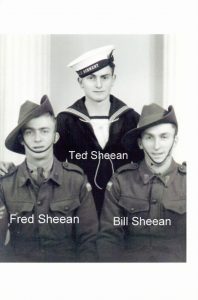

Australia’s naval personnel know this WWII tale. The corvette Armidale was sunk by overwhelming fire from Japanese aircraft. While she was sinking fast, Ordinary Seaman Teddy Sheean went back to his Oerlikon 20mm anti-aircraft gun and manned it to the end, even as the ship went down beneath him. Sheean was awarded a Mention in Despatches, but many think he should have received the Navy’s first Victoria Cross.

Armidale was sunk south of Timor after an operation emanating from Darwin. A variety of small ships were supporting operations into the islands of what is now Indonesia and Timor. On 1 December 1942 Armidale was lost in a short sharp action. Japanese Zero fighters and Betty bombers attacked her in the early afternoon with overwhelming force and hit her with at least one or maybe two deadly torpedoes.

The survivors took to the ship’s boats and rafts. There was a long delay in search and rescue operations mainly as it was assumed the sunken Armidale was maintaining radio silence as ordered. A search was commenced two days after the sinking.

However, another group of other survivors on a large raft were never seen again after located by an aircraft. It is probable they died of exposure to the sun and a lack of food and water.

An inquiry was held into the Armidale’s sinking: normal practise in such situations. It was a straightforward affair. The conclusion was that “all reasonable steps were taken and that the actions of the Commanding Officers were correct,” referring to the ships present: Armidale, Kuru, Castlemaine and Kalgoorlie.(3)

How did the story that Richards was shunned come about? It probably evolved in a number of ways.

The survivors of the Armidale were scattered by time and tide after their recovery. Some were injured; all were exhausted by their ordeal in the ship’s boats. They were however still members of the Navy, and they were separated by necessity. Many were hospitalised. Many were sent south from Darwin. Others stayed for the subsequent Inquiry. They were taken into other ships’ companies – posted – and tossed about by the needs of the force. If they ever saw each other again it would be a matter of luck and whether they wished to organise it themselves. Therefore an accurate picture of the career of their former commander never eventuated.

If this seems harsh by the standards of today’s world, then it pays to ponder how times have changed and how hard Australia was fighting – for its life. 1942 was a terrible year: the force had lost ships large and small – from the cruiser HMAS Perth to the destroyer Voyager to the sloop Yarra to the tiny lugger Mavie – all lost in northern waters to overwhelming Japanese force. The loss of life was measured in the thousands. The previous year the RAN had suffered what is still its biggest disaster of all time: 645 men sunk without trace on board HMAS Sydney off the Western Australian coast in battle with the raider Kormoran. At the height of WWII there was no time to do more than what was physically necessary for the men of Armidale.

• Survivors on the liferaft may have been taken on board a Japanese warship and executed

• Japanese aircraft found them and machinegunned them all

• Dutch soldiers killed all of the Australians for the raft’s food and water

• Unnamed naval personnel from the Armidale were treated badly as survivors, without proper issue of new clothing

• Without evidence, the Navy minimised any publicity to protect its senior officers.

Walker said of Richards that he: ”…was never given another naval command,” (4) implying that this was a sign of the Navy’s displeasure over his handling of Armidale. He then goes into some detail:

…there was never any award or recognition for Armidale’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Richards….The lack of an award would not have worried the modest, self-effacing Richards, but what really hurt him what that although he was soon physically fit again the Navy refused to give him another command. Several members of the crew had asked could they serve under him again and he had agreed, not knowing that they would never get the chance. He grieved over that until he died in 1967.

We do not know of the accuracy of these statements. The names of the crew members are not given. Nor is there a record of anyone’s interview or communication of any sort with Richards.

Walker makes three serious allegations about the subsequent handling of the loss of Armidale. First, he asks why no medals were ever awarded to Armidale survivors. Second, why Sheean was only mentioned-in-despatches, and third, why the commanding officer of Armidale, Lieutenant-Commander Richards, did not get another command. His answer to all three questions is that the Navy wanted to cover up the loss.

I cannot answer the questions he raises. For what it is worth, I find what actually happened incomprehensible and very unfortunate. However, to suggest it amounted to a cover-up or that the RAN was actively responsible is unwarranted.(6)

Frame was only reviewing the book, and as such had no duty to check every fact asserted. But the allegation became accepted. Websites such as U-Boat Net also repeat it by not listing Richards’ other command, although someone there has noted he was promoted commander.(7)

In the research for Honour Denied, Teddy Sheean Tasmanian Hero, an analysis of why Teddy Sheean was not awarded a VC, Richards’ Service Record was recovered from the National Archives of Australia. Lieutenant Commander Richards was indeed given other sea-going commands. His Service Record lists his appointments, including Armidale and beyond. He was next appointed to the corvette Katoomba as CO, but this was cancelled – the reason has not yet been found. He served at the shore base Moreton as Naval Berthing Officer; and then was posted to Darwin to the base HMAS Melville in the same capacity. Later was appointed in command to another corvette, HMAS Burnie. He then took over command of two identical ships in succession: Landing Ship (Tank) 3022 and LST 3008.

The LSTs were big ships, over 2000 tons; of 345 feet (105 m) in length, and designed to carry tanks, artillery, and troops for amphibious landings. They were well defended from air attack by four 40mm Bofors in two twin mounts and six 20mm Oerlikons in two twin and two single mounts.(8)

Richards probably reflected on this comparison with his lost corvette on occasion.

A year and a half after the end of the war, on 31 December 1946, Richards was promoted to full commander. This is significant for two reasons. Post-war the Navy was contracting sharply, down from its peak of nearly 40, 000 personnel to well under twenty thousand. There was usually no work available for a Reserve lieutenant commander, in fact there was a lot less available for Permanent Force members. It is a myth to think that “the Navy” either then and now gazes down from a mountain and bestows favours, god-like, on those it likes, while dispensing thunderbolts to those it doesn’t. More likely Richards’ combination of experience, availability, and abilities placed him into positions.

But it is most significant that Richards was promoted commander. This is the equivalent from the step up from army major to army lieutenant colonel. Most naval officers do not rise above lieutenant commander. To gain the coveted “step” upwards brings with it the conferral of a new cap, this one with gold braid on its peak, hence the expression “brass hat.” Again, Navy does not bestow from a pinnacle such favours, but nevertheless the list of promotions was, and is, closely scrutinized by the very senior officers of the force.

If Richards was out of favour generally with the Navy, as Walker implies, it is extremely unlikely he would have been given this promotion. Indeed, this appointment would have been reviewed several times by the most senior figures in the force, and it could have been removed with a pen-stroke, and Richards never told of such an action. That the promotion was indeed promulgated is the reverse of what Walker was suggesting: it even implies the Navy wanted to recognize the officer who had lost Armidale in heroic circumstances, and was acknowledging the loss of the corvette, not covering it up.

Richards was also recognised towards the end of the war with the Reserve Decoration, on 11 December 1944.(9) This was an Imperial honour given for 15 years service by members of the Defence Force. It carried the post-nominal “RD”, and was the only long service award in the Australian honours system that carried¬¬¬ a post-nominal entitlement. In 1999 it was replaced by the Defence Long Service Medal.(10) Significantly however, the Navy could even have curtailed this award, simply by terminating Richards’ service. If his time had been tainted by losing Armidale, he could have been denied this honour.

So why did Walker persist with his allegation? The answer may lie in the timeline:

• 1942 Armidale action

• 1952 Richards retires from the Navy

• 1967 Richards dies

• 1990 Walker’s book published

• 2004 Richards’ records opened at National Archives

Walker most likely never tried to access Richards’ Service Record which certainly was still sealed at the time he published his book. The Archives service have strict rules about opening up records, and the first time one is accessed the date is recorded. It must be doubtful that he ever interviewed members of Richards’ family, and it is unknown whether he ever met Richards, although he served in the Navy himself in WWII. The style of his book is to use direct quotes from people he interviewed, and neither of these two possible sources are used.(11)

Lieutenant Commander David Richards RD RAN was, despite stories to the contrary, an honoured and respected member of the Royal Australian Navy. He fought his ship in the highest traditions of a courageous and capable Service.

-o-o-O-o-o-

* Dr Tom Lewis OAM is a military historian. A retired naval officer, his next book Honour Denied, Teddy Sheean Tasmanian Hero has just been released by Avonmore Books. It contains much analysis and new revelations about Sheean and the Armidale combat action.

________________________________________________________________________

Footnotes

(1) National Archives of Australia. “Naval Operations – Report by Naval Board on loss of HMAS “Armidale” 4/12/42 – 12/1/43.” MP138/1, 603/280/945. (p. 4)

(2) The full analysis of this is contained in Honour Denied.

(3) National Archives of Australia. “Naval Operations – Report by Naval Board on loss of HMAS “Armidale” 4/12/42 – 12/1/43.” MP138/1, 603/280/945.

(4) Walker, Frank. HMAS Armidale – The Ship that had to Die. NSW: Kingfisher Press, 1980. (p. 99)

(5) The Gun Plot. Website. “Survival at sea: In the whaler after the sinking of HMAS Armidale in 1942. A personal account by Rex Pullen.“ http://www.gunplot.net/main/content/hmas-armidale-survivors-story. Accessed June 2013.

(6) Frame, Tom. Headmark. “The Ship History — Recording or Distorting the Navy’s Past?“ Journal of the Australian Naval Institute. Volume 17, February 1991, Number 1. (pp. 44-48)

(7) U-Boat Net. Website. http://www.uboat.net/allies/warships/ship/3699.html Accessed June 2014.

(8) Gillett, Ross. Australian and New Zealand Warships since 1946. Brookvale, New South Wales: Child & Associates, 1988. (p.35)

(9) Full title: Decoration for Officers of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve. I am grateful to Dr David R Leece, PSM, RFD, ED, the Editor of United Service for explaining this to me.

(10) “It’s an Honour.” Website. https://www.itsanhonour.gov.au/honours/awards/medals/reserve_force_decoration.cfm

(11) NAA: A6769, WALKER FB.